Occupational therapy plays a pivotal role in helping individuals regain their independence and improve their daily life skills. To achieve the desired outcomes, occupational therapists rely on a variety of tools and equipment tailored to assess, intervene, and enhance the lives of their clients. Understanding these tools not only aids the therapists in their mission but also allows business owners to better support their practices and ensure an optimal environment for therapeutic work. This article delves into three pivotal chapters: the first explores functional assessment tools, the second discusses assistive devices that aid patients, and the third focuses on essential digital resources and workplace equipment that help streamline occupational therapy practices.

Harnessing Functional Assessment Tools: A Cornerstone for Effective Occupational Therapy

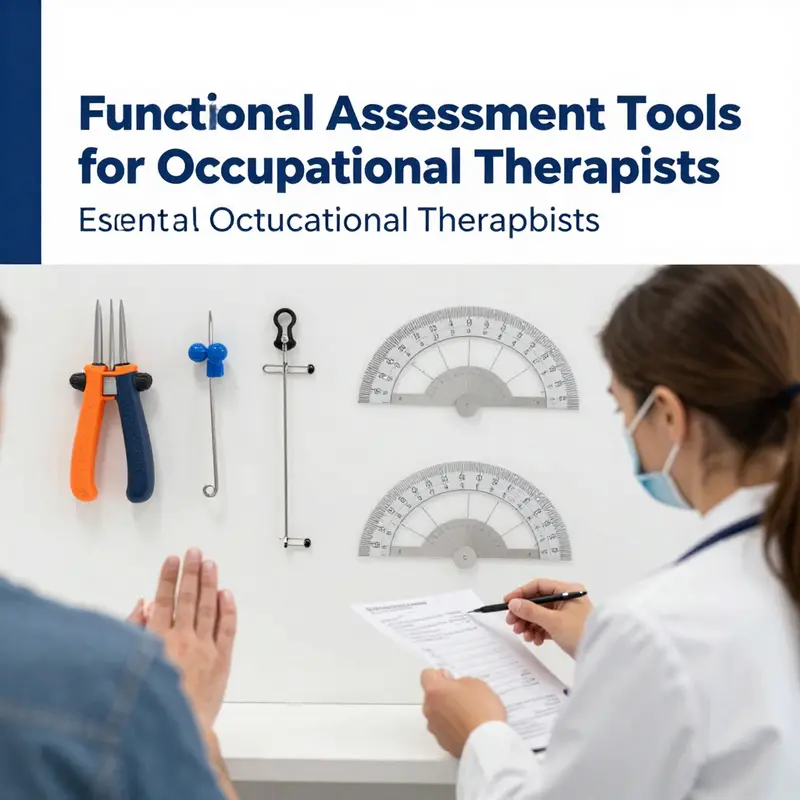

Functional assessment tools are central to the practice of occupational therapy, serving as the foundation upon which individualized treatment plans are built. These tools meticulously gauge a client’s ability to engage in day-to-day activities, revealing not only physical capacities but also cognitive and psychosocial aspects essential for meaningful participation in everyday roles. Through comprehensive evaluation, occupational therapists can identify specific challenges and devise interventions that restore independence and improve quality of life.

At the core of functional assessment lies the necessity to understand the client from a holistic viewpoint. Unlike generic medical exams that may focus solely on physiological parameters, occupational therapy assessments explore the interaction between a person’s abilities, the demands of daily living, and their environment. This person-centered perspective ensures that evaluation and intervention honor both the individual’s unique circumstances and personal goals.

One widely embraced approach is the use of client-centered tools such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). This instrument facilitates a dialogue where clients identify and prioritize activities that hold significance for them, enabling the therapist to measure performance and satisfaction in these self-chosen tasks. The COPM’s strength lies in its empowerment of clients, affirming their voice throughout the rehabilitation journey. It transforms assessment into a collaborative process, fostering engagement and motivation.

Parallel to subjective measures are standardized tests like the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS), which objectively analyze the quality of a person’s motor actions and cognitive processing during activities. By observing task performance in naturalistic or simulated settings, therapists can discern patterns of difficulty that might not otherwise be verbalized. The AMPS, for instance, highlights breakdowns in planning, sequencing, or physical execution, guiding therapists in crafting targeted interventions.

Tracking changes over time is equally crucial, especially when addressing progressive conditions or recovery phases. Tools such as the Deterioration of Performance Assessment (DPA) provide insight into how a client’s occupational performance evolves. By documenting shifts in ability, occupational therapists can adjust treatment intensity, methods, and goals responsively.

Furthermore, the Role Checklist serves as a valuable instrument that explores not only what clients do but what roles they perceive as important. Recognizing these roles—parent, employee, student, or community member—places the occupational therapist’s work within the broader social and emotional context of the individual’s life. Recovery of role performance often underpins increased self-esteem and life satisfaction, reinforcing the therapeutic process.

Recognizing the complexity of daily living, assessments extend into evaluating Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). These tasks, such as managing finances, shopping, or medication management, demand higher cognitive and physical demands than basic self-care. Scales measuring IADLs help identify those areas where support or skill-building is necessary to maintain independence.

For the aging population, functional assessment tools tailor evaluations to mobility and independence in later life. The Elderly Mobility Scale (EMS) specifically captures abilities like sitting balance, walking, and transferring, which directly impact safety and autonomy. Assessing these functions is critical in fall prevention strategies and for enhancing community participation.

Cognitive evaluation, integral for clients with brain injuries or neurodegenerative diseases, is addressed using instruments like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). This quick but effective screening targets memory, orientation, attention, and language—domains heavily influencing the capacity to perform complex occupations.

An additional layer of assessment focuses on executive functions, the high-level cognitive skills needed to initiate, plan, and complete tasks. The Executive Function Performance Test (EFPT) bridges traditional cognitive assessment with functional performance by observing clients tackling real-world tasks. This alignment with everyday challenges ensures therapists appreciate how cognitive deficits translate into practical difficulties.

In rehabilitation settings, the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is a gold standard for quantifying the degree of assistance a client requires. By rating performance in motor and cognitive domains, the FIM tracks progress meticulously, enabling therapists and multidisciplinary teams to make informed decisions about care transitions and support needs.

The strategic integration of these assessment tools allows occupational therapists to practice evidence-based care that is both measurable and meaningful. It anchors interventions in data, supports insurance and institutional documentation, and—in most importantly—centers the client’s lived experience.

In addition, the application of these tools is not restricted to clinics but extends into community, school, and home environments, adapting to diverse client needs. Such versatility exemplifies how occupational therapy is uniquely positioned to enhance participation across the lifespan and in varied contexts.

While physical and cognitive assessments dominate, occupational therapists also harness digital innovations to refine their evaluation processes. Mobile applications and electronic health records increasingly facilitate seamless data collection and sharing, optimizing continuity of care. Moreover, therapists can access downloadable resources, such as comprehensive toolkits in PDF format, to support their clinical decision-making effectively.

Equally important is the therapist’s clinical judgment in selecting and interpreting these tools. Functional assessments must be sensitive to cultural, linguistic, and individual differences to avoid misinterpretation. The ultimate aim is to build a therapeutic alliance where assessment fuels empowerment rather than mere diagnosis.

Furthermore, functional assessments contribute to health promotion and mental well-being by identifying occupations that enrich a client’s life and foster resilience. For deeper insight into how occupational therapy supports mental health, exploring tailored therapeutic exercises and engagement strategies can be illuminating. Discover detailed approaches on mental health support in occupational therapy here.

Occupational therapists rely heavily on rigorous training and continual professional development to maintain proficiency in these tools, ensuring assessments remain valid and reliable amid evolving best practices. Board certifications and professional associations provide guidelines and updates, empowering therapists to deliver high-quality care.

To explore and implement these functional assessment tools successfully, practitioners often refer to authoritative sources such as the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). AOTA offers comprehensive information on tool validity, normative data, clinical application, and research findings to support therapists worldwide.

Visit the AOTA Official Website for extensive resources on functional assessment.

In sum, functional assessment tools are indispensable in occupational therapy. They offer a structured yet dynamic means to unravel the layers of client ability and challenge. Through thoughtful assessment, occupational therapists unlock the potential for clients to return to valued activities and roles with greater independence and satisfaction. This indispensable process is not merely a measurement exercise but a profound step toward healing and meaningful living.

Practical Assistive Devices: Selection, Customization, and Integration for Occupational Therapy

Assistive Devices: Practical Choices for Occupational Therapists

Occupational therapists rely on assistive devices to bridge the gap between a person’s current abilities and the tasks they want or need to perform. These devices range from simple, low-cost aids that restore independence in self-care to complex, technology-driven systems that transform an individual’s interaction with their environment. The therapist’s role is not merely to hand over equipment; it is to match devices to function, context, and goals, to ensure long-term use, and to adapt or customize solutions when standard options fall short. This chapter examines the decision-making processes, interdisciplinary collaborations, and implementation strategies that turn assistive devices from tools into meaningful supports in daily life.

At the heart of effective device selection is a clear evaluation. Assessment begins with a functional profile that captures the client’s strengths, limitations, routines, and priorities. A thorough profile includes physical parameters such as range of motion and grip strength, cognitive factors like attention and memory, sensory considerations including vision and proprioception, and environmental features such as home layout and workplace demands. Gathering observational data through task analysis is essential. Watching a person prepare a meal, manipulate clothing fasteners, or navigate a bathroom reveals subtle barriers that questionnaires may miss. Each observed breakdown becomes a target for intervention and a constraint on the choice of device.

Once needs are identified, the therapist narrows options through a pragmatic lens. Simpler solutions should be considered first because they are often less expensive, easier to maintain, and more likely to be accepted by the user and caregivers. Examples include non-slip mats, built-up utensil handles, and long-handled shoehorns. When basic devices cannot achieve the necessary functional gain, therapists consider more complex assistive technologies. These include adaptive seating, upper-limb orthoses, environmental control units, powered mobility, and electronic aids for daily living. The guiding questions are consistent: does the device enable the person to perform the targeted task reliably? Is it safe in the intended environment? Can the user operate it with available support? Will it integrate into the user’s life and routines?

Customization transforms assistive devices into bespoke solutions. Rehabilitation engineering and collaborative design enhance the therapist’s toolkit. Working with engineers or technicians, therapists can modify commercial devices, fabricate custom splints and mounts, or design user interfaces that accommodate specific impairments. Customization may be low-tech, such as padding a handle to improve comfort and grip, or high-tech, such as programming a switch interface for a powered wheelchair. When modifications are needed, therapists balance function and form: the altered device must still be cosmetically acceptable and easy to maintain. Interdisciplinary partnerships bring complementary expertise—engineers contribute materials and mechanisms, therapists bring human factors and task analysis, and users supply lived experience. This synergy often produces creative solutions that a single discipline cannot achieve alone.

Prescription is a clinical and documentation process. A sound assistive technology prescription includes a clear statement of goals, device specifications, trial outcomes, training plans, and follow-up arrangements. The prescription must be defensible: it should justify the chosen device based on assessment findings and expected functional outcomes. For funding and reimbursement, detailed documentation is essential. Therapists often need to demonstrate that less intensive alternatives were considered and why they were insufficient. Objective measures, such as timed task performance, independence ratings, and standardized assessments, strengthen a case for approval. The prescription should also outline contingency plans and carryover strategies to handle device failure or changing needs.

Trials and fitting sessions are central to successful long-term use. Short demonstration trials in a clinical setting can screen options, but home trials are often the decisive test. The device that works in the clinic may not suit the home where door widths, threshold heights, and kitchen layouts differ. A trial period allows the therapist to observe real-world use, gather feedback, and refine fittings. Training during trials emphasizes safety, maintenance, and troubleshooting. The therapist teaches the user and caregivers how to operate buttons, charge batteries, and secure straps. Clear, simple written or pictorial instructions support learning, and follow-up visits or telehealth check-ins reinforce skills. Embedding training within the tasks users value increases adoption and retention.

Training itself must be graded and contextual. Skill acquisition benefits from breaking tasks into manageable steps, using repetition combined with real-life contexts, and providing immediate, specific feedback. For complex devices, building competency may require multiple sessions spaced over weeks. Therapists employ strategies such as backward chaining for multi-step tasks, environmental cues to prompt sequencing, and simplifying interfaces by labeling controls. Cognitive impairments demand compensatory techniques: combining auditory prompts with visual checklists or using automation to reduce memory load. The aim is to ensure safety and independence while minimizing caregiver burden.

Maintenance and durability are practical considerations that influence device selection. Devices exposed to moisture or heavy use require robust materials and clear care instructions. Therapists advise clients on routine checks, cleaning procedures, and signs of wear that necessitate repair. Where possible, selecting devices with local service support simplifies repairs and reduces downtime. For electronic devices, battery management and software updates can be common pitfalls. Therapists plan for these by arranging access to technical support and ensuring that users can perform basic upkeep, such as charging or replacing batteries.

Measurement of outcomes guides ongoing decisions. Therapists use both objective and subjective metrics to gauge effectiveness. Objective measures include task completion rates, time to complete tasks, and range of motion. Subjective measures capture user satisfaction, perceived independence, and device usability. Combining these perspectives yields a fuller picture of whether the intervention meets the person’s goals. Regular reassessment is necessary because needs change over time. A device that once offered great benefit may become insufficient as conditions progress or as the user’s goals evolve. Scheduled reviews allow timely upgrades, modifications, or discontinuation as appropriate.

Funding, procurement, and ethical considerations are intertwined. Funding streams vary widely and influence device choices. Therapists must be familiar with local funding policies, insurance criteria, and charitable resources. Ethical practice requires transparency about costs, realistic expectations, and alternatives. When resources are limited, therapists prioritize interventions with the highest functional yield and consider staged approaches—starting with inexpensive items and moving to complex solutions if needed. Involving the client and family in these decisions respects autonomy and fosters ownership of the chosen solution.

The adoption of digital tools has accelerated in assistive technology practice. Prescription aides, decision-support algorithms, and online repositories help clinicians match devices to needs. Emerging tools can integrate standardized assessment algorithms and evidence-based guidelines into the selection process. While these resources streamline workflow, clinical judgment remains essential. Digital tools should complement, not replace, the therapist’s expertise in contextualizing solutions for individual lives. Therapists should critically appraise digital recommendations, ensuring that suggested devices account for the user’s environment, culture, and preferences.

Successful implementation relies on environmental fit. Devices function best when the physical and social environment supports their use. Home modifications—such as grab bars, ramps, and lowered counters—often work in tandem with personal devices. Education of household members and workplace colleagues is also crucial. Small adaptations in routines or expectations can greatly increase the benefit of an assistive device. Occupational therapists act as advocates and educators, helping communities understand how devices reduce barriers and promote participation.

Sustainability and scalability matter when interventions move beyond a single client. Rehabilitation engineering programs and fee-for-service models that develop technical aids can scale solutions across populations. When a custom modification proves effective, documenting the design and making it reproducible can magnify impact. Therapists should document modifications, gather outcome data, and, when appropriate, share designs within professional networks. This approach supports innovation while maintaining quality and safety.

Interdisciplinary collaboration is not optional in complex cases. Occupational therapists coordinate with prosthetists, orthotists, physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, engineers, and manufacturers. Each discipline contributes specialized knowledge that refines device selection and training. For instance, a powered mobility assessment often involves a physical therapist for seating and posture, an engineer for mounting technical controls, and an occupational therapist for task-specific control strategies. These teams create holistic solutions that maximize function and minimize secondary complications.

Looking ahead, assistive devices will continue to evolve as sensors, artificial intelligence, and connectivity become more accessible. Devices that adapt in real time to user performance hold promise for dynamic support. However, technological advancement will not supersede the fundamental occupational therapy tenets: person-centered assessment, meaningful activity engagement, and contextualized intervention. Therapists will remain essential in interpreting data, translating technology into everyday use, and ensuring that devices serve human goals rather than technological novelty.

For therapists seeking practical guidance on device selection and intervention strategies aligned with therapeutic techniques, a resource on common therapeutic approaches can provide helpful context and methods to integrate device-based solutions into treatment plans: techniques used in occupational therapy.

For an in-depth examination of integrated rehabilitation engineering programs and technical aid delivery, see this authoritative study which outlines program models, development methods, and case examples that illustrate the interdisciplinary approach described here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10123456/.

The Digital Clinic Floor: How Wearables, EHRs, and the OT Workspace Shape Everyday Therapy

Occupational therapy sits at an intersection where human care, practical science, and everyday living converge. The chapter you are about to read explores how digital resources and the physical workspace collaborate to support assessment, intervention, and progress in daily activities. In contemporary practice, the tools and equipment an occupational therapist selects are not isolated gadgets but parts of an integrated system. They enable clinicians to observe, evaluate, and intervene with a precision that was unimaginable a generation ago, while also shaping the patient experience to be more engaging, collaborative, and empowering. The workspace itself—an orderly, well-equipped environment—serves as a stage where technology and touch work in concert to restore independence, safety, and confidence in everyday tasks. The shift toward digital resources does not replace the hands-on, person-centered core of therapy. Instead, it amplifies it, providing data-informed insights, scalable patient education, and remote access that extends care beyond clinic walls. A thoughtful synthesis of digital tools and workplace equipment thus forms the backbone of modern occupational therapy practice, guiding treatment from initial evaluation to meaningful daily participation.

At the heart of this transformation are electronic health records (EHRs). EHR systems do more than store notes; they provide a living thread that links the therapist’s observations with progress over time. When an OT documents ROM measurements, sensory assessments, and functional outcomes in real time, the entire care team gains visibility into the patient’s trajectory. This visibility is not merely about compliance or accountability. It supports a nuanced, collaborative approach to goal setting, where changes in the patient’s performance are interpreted against a robust history of data. The benefits extend beyond the clinician’s desk. Real-time updates foster smoother communication with physicians, nurses, rehabilitation assistants, and family members who participate in home programs. The patient and their caregivers also experience a more transparent treatment process: they can review the plan, monitor changes, and better prepare for the next therapy session. Privacy and security, of course, are integral to any discussion of digital records. Effective OT practice embeds strong access controls, clear consent protocols, and patient-centered data governance, ensuring that the benefits of digital documentation do not come at the expense of trust or safety.

Beyond documentation, telehealth platforms have opened a wide corridor for assessment and intervention. Teletherapy enables remote evaluations that preserve time and physical stamina for patients whose mobility is limited or whose schedules are constrained by work, caregiving, or transportation barriers. A well-designed telehealth encounter leverages video observation of functional tasks, caregiver reporting, and remote instruction to support home-based interventions. For many clients, the ability to practice in their own environment—seeing how a self-feeding routine or morning dressing task unfolds on familiar terrain—yields insights that are harder to capture in a clinic. Telehealth also creates a continuity of care during hospital-to-home transitions, rehabilitation stays, or community-based programs where follow-up is critical to sustaining gains. Clinicians use asynchronous tools—recorded demonstrations, digital checklists, and secure message exchanges—to reinforce learning between live sessions. While the technology is powerful, its value rests on thoughtful practice design: clear goals, reliable internet access, user-friendly interfaces, and contingency plans for technical hiccups. The digital bridge also invites caregivers into the therapeutic process as active partners, equipped with home-practice instructions that they can review and implement with confidence.

Assistive technology and smart systems sit at another crucial junction of therapy and daily life. Adaptive computer interfaces, voice-activated software, switch-access programs, and smart home controls are not merely devices; they are enablers of autonomy. For a client with limited hand function, for instance, a switch-activated system or a voice-driven interface can transform a kitchen task that once required assistance into one the person can manage with minimal support. Similarly, intelligent environmental controls—lights that respond to voice or motion, thermostats that modulate comfort, and door systems that accommodate varied mobility levels—reduce the cognitive and physical load that often accompanies simple activities such as cooking, grooming, or managing medications. The goal is not to replace skills but to compensate for barriers where they exist, offering alternative pathways to the same functional end. In this sense, assistive technology becomes a co-therapist, guiding the sequence of steps, reminding the patient of safety considerations, and providing immediate feedback about performance.

Wearable sensors and biofeedback devices are reshaping how therapists observe movement, posture, and efficiency. The data they generate introduce a level of objectivity that complements clinical judgment. Gait patterns, reach trajectories, finger tapping speed, and trunk stability can be quantified over the course of a treatment plan, creating concrete benchmarks for progress. When integrated with the patient’s activity logs and EHR, these metrics illuminate how improvements in strength or coordination translate into real-world function. Biofeedback can also foster patient engagement by offering real-time information during a task. A client can, for example, see a visualization of how their posture shifts when reaching for an object, which encourages self-correction and awareness—critical elements in rehabilitation. The challenge lies in balancing data collection with patient comfort and privacy, ensuring sensors are unobtrusive and that data interpretation remains clinically meaningful rather than overwhelming. The clinician’s skill in translating streams of numbers into actionable insights is essential; data alone does not drive change, but it can illuminate patterns that guide coaching, task modification, and progression.

Within the realm of evaluation and intervention, the equipment in the therapist’s cabinet and clinic play a foundational role. Practical measurement devices—such as goniometers for joint range of motion and simple tools for manual dexterity assessment—continue to be indispensable. Modern practice may also incorporate digital ROM devices or smartphone-based measurement apps that offer higher reliability and easier documentation. Such tools fit naturally into a clinic that values precision while remaining respectful of the patient’s comfort and time. Equally critical are the training and rehabilitation devices that support motor learning and functional recovery. Balance boards, resistance bands, therapy balls, and proprioceptive cues provide controlled, progressive challenges that help patients rebuild strength, coordination, and confidence. The design of therapy activities often hinges on real-world relevance: tasks that resemble daily routines, such as preparing a simple meal, organizing a workspace, or performing a self-care sequence, become the vehicles through which therapeutic gains transfer to life beyond the clinic. When these tasks are embedded in a multisensory, responsive environment—where the patient can see, feel, and hear progress in real time—motivation and adherence are often strengthened, and the therapist can adjust the difficulty in a fluid, individualized manner.

The role of digital resources in supporting patient education cannot be overstated. A well-curated toolkit of digital handouts, video demonstrations, printable checklists, and home program templates helps patients engage with therapy between sessions. PDF-based resource packs, widely accessible on tablets, laptops, and smartphones, can be shared with patients and families to reinforce instructions, safety tips, and exercise sequences. When these resources are integrated with the EHR, therapists can assign specific materials, track which items were reviewed, and adapt home programs based on patient feedback and performance data. In this way, digital resources do more than disseminate information; they create a structured learning pathway that respects individual learning styles and literacy levels. The patient’s ability to revisit instructions at their own pace reduces anxiety and supports mastery, particularly for cognitive or neurological challenges where repetition and consistency matter.

The physical workspace itself matters as much as the digital toolkit. An efficient OT clinic balances comfort, accessibility, and workflow. A well-designed desk area supports organized note-taking and quick access to digital resources. A patient chair and an adjustable treatment bed accommodate a range of body sizes and therapeutic tasks, while an instrument cabinet or cart keeps essential supplies organized and within reach. Storage solutions reduce clutter, which in turn minimizes cognitive load during complex sessions. The layout should encourage safe, independent navigation for patients and ensure that assistive devices—whether for seating, transfers, or daily activities—are readily available and correctly sized. In a typical space that respects the principles of universal design, equipment is selected not only for current tasks but also for future needs, anticipating changes in function and mobility that may arise during the course of rehabilitation. In such an environment, technology does not overwhelm; it supports. The therapist remains the guide, but the tools provide a structured, responsive framework that helps patients practice, monitor, and generalize skills in meaningful contexts.

All these elements—digital records, remote platforms, assistive technologies, wearables, measurement devices, and a thoughtfully organized physical space—interact to create a seamless therapeutic journey. Data from wearable sensors may feed into the EHR, where clinicians interpret trends and adjust interventions. Telehealth sessions can be used to introduce new home-based tasks, while in-clinic sessions focus on hands-on skills and progress assessment. The patient’s learning experience is enriched by direct demonstrations, guided practice, and the immediate feedback provided by sensors or smart devices. This integrated approach supports a patient-centered model of care in which treatment decisions are grounded in real-world performance, not merely in theoretical ranges or isolated test scores. It also acknowledges that therapy occurs across multiple environments—clinic, home, school, or community settings—each with its own demands and opportunities for practice.

The digital and physical components of OT practice also impose responsibilities. Clinicians must design workflows that are efficient and resilient in the face of technical challenges. They must ensure that patients understand how to use digital tools, protect their privacy, and maintain engagement with home programs. The clinical team must stay up-to-date with evolving platforms, standards of care, and ethical considerations around data collection and sharing. Training across administrative staff, clinicians, and caregivers is essential so that technology serves as an ally rather than a barrier. When this alignment exists, the therapy process gains momentum: assessments become more precise, interventions become more adaptable, and outcomes become easier to monitor and communicate to patients, families, and other care providers.

As you reflect on the landscape of tools and equipment described here, consider how this integrated approach translates into everyday practice. The clinical encounter becomes a collaborative investigation into what a person can do, what they want to do, and what adjustments might enable them to participate in meaningful daily routines. A well-chosen mix of digital resources and physical equipment helps therapists observe performance more reliably, teach skills more efficiently, and empower patients to take ownership of their rehabilitation. The patient’s home, workplace, and community become windows for practice and feedback, expanding the possibilities for independence far beyond the therapy room. In this sense, the OT’s toolkit is not merely a collection of devices but a carefully choreographed ecosystem that supports patients through the full arc of recovery and adaptation.

For readers who want to explore the practical dimensions of expanding an OT toolkit with evidence-informed methods, the discussion of techniques used in occupational therapy provides a helpful synthesis of approach and method. This resource, which you can explore here: Techniques used in occupational therapy, bridges theory and practice by illustrating how therapists tailor strategies to individual goals, functional contexts, and patient preferences. Such insights remind us that tools are only as effective as the clinical reasoning that guides their use, and that the most successful therapy arises when digital resources and physical equipment are aligned with patient-centered outcomes, safety, and dignity.

In sum, the modern occupational therapist works with a dynamic landscape of digital resources and workplace equipment that together enable more precise assessments, more engaging interventions, and more reliable progress tracking. The synergy between the clinic floor and the cloud, between hands-on skill practice and wearable data, between printed handouts and interactive demonstrations, creates a robust framework for helping people reclaim independence in daily life. As digital tools become more sophisticated, the core of OT remains steadfast: understanding the unique activity challenges of each person, supporting meaningful goals, and guiding the gradual reimagining of daily life so that activity and independence can coexist with safety, confidence, and joy. The chapter you have read highlights how technology and environment are not separate chapters in a clinician’s story but two threads woven into a single, continuous narrative of care. AOTA provides a broader view of how digital tools are transforming occupational therapy practice, illustrating the ongoing evolution of the field and inviting ongoing professional learning and thoughtful integration of new capabilities.

External resource for further exploration: American Occupational Therapy Association — https://www.aota.org/

Final thoughts

The tools and equipment employed in occupational therapy are integral to providing effective care and enabling patients to regain their independence. Business owners have a crucial role in supporting occupational therapists by facilitating access to these resources and ensuring an environment conducive to rehabilitation. By investing in functional assessment tools, assistive devices, and digital resources, practices can enhance patient care and foster better therapeutic outcomes. Ultimately, the commitment to equipping occupational therapists will translate into improved quality of life for clients and greater success for your business.