Espresso has carved out a distinguished niche in coffee culture, but many business owners may wonder: are espresso beans fundamentally different from coffee beans? Understanding this topic is crucial for making informed purchasing and preparation decisions. This exploration will clarify the distinctions—beginning with roast levels, moving onto brewing methods, and finally addressing grind size and consistency. Each chapter aims to enhance your grasp of how these factors influence the potential for profit and customer satisfaction in your business.

Dark Intent: Why Espresso Beans Aren’t a Different Species, but a Deliberate Roast Profile

The question many newcomers ask is simple yet revealing: are espresso beans the same as coffee beans? The honest answer is yes and no at once. The beans themselves are the same species, harvested from the same coffee shrubs, often the same varieties, and sometimes even the same lot. What changes is how those beans are treated after harvest and, crucially, how they are brewed. In the language of coffee, “espresso beans” function as a label that encodes a deliberate choice about roast level, grind, and a brewing method that together aim to coax a specific kind of coffee experience. There is no separate plant species, no magical bean that only works in a machine. There is, instead, a roasting and preparation philosophy designed to perform optimally under pressure and within a short extraction window. When we separate the bean from the brew, we find that the espresso method asks the bean to reveal its character in a way that contrasts with drip or French press, and that distinction often gets misread as a change of bean rather than a change of intention.

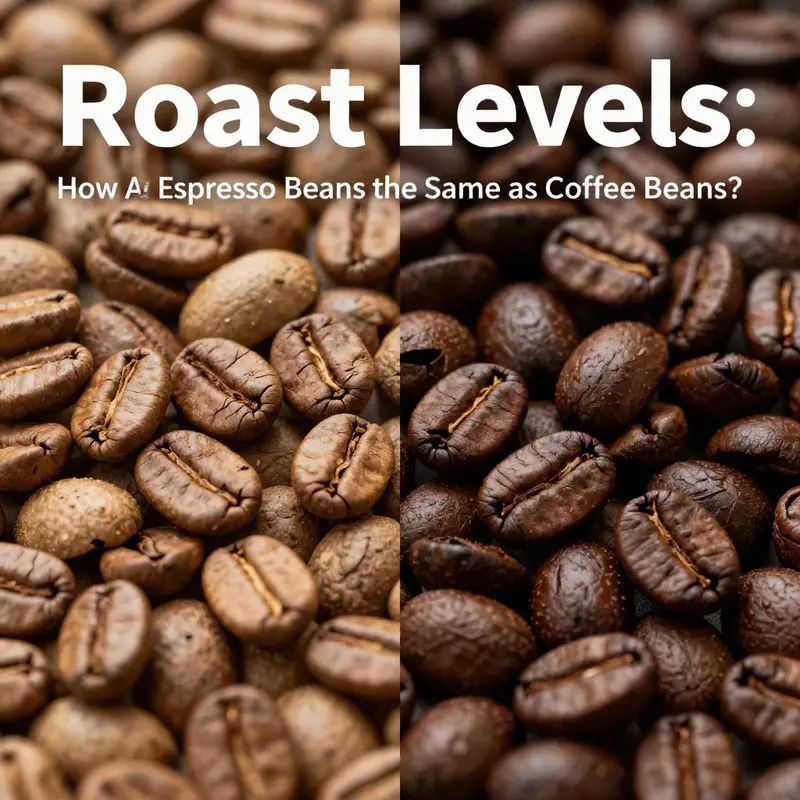

To understand this distinction, it helps to begin with roast level, the most visible and influential variable in the espresso equation. Espresso roasts skew dark, a choice guided by both chemistry and human taste. Dark roasts promote a bolder, more lacquered flavor profile. They temper acidity by kissing it with a gentle bitterness and toasty sweetness, which can feel like a concentrated form of comfort in a single shot. The oils that migrate to the surface during a longer roast also contribute to a fuller mouthfeel and to a crema that looks almost velvety in the cup. It is not that dark roasts erase brightness; rather, they tend to balance brightness in a way that remains harmonious when exposed to the intense pressure of a fast, high-temperature extraction.

The relationship between roast and crema is particularly telling. Crema arises from tiny emulsions of oils, proteins, and sugars that bloom when hot water rushes through the compact bed of ground coffee under pressure. In a dark roast, these oils are more abundant on the surface, aiding crema formation. But crema is not a mark of quality by itself; it is a sensory signal that the extraction is going smoothly. A well-pulled espresso shot with a thick, caramel-brown crema often indicates that the grind size is well matched to the pressure and time, and that the roast has created a balance between sweetness and bitterness. The dark roast’s more pronounced oiliness and caramelization also contribute to a body that feels syrupy and persistent, a desirable trait for many espresso drinks that rely on a robust backbone to support milk or other flavors.

Beyond roast level, the grind and the brewing technique are inseparable from the bean’s ability to sing in an espresso machine. Espresso grounds need to be finer than those for drip coffee, but consistency matters even more than fineness. A grind that varies even slightly can produce uneven extraction, which results in sour notes, muddy flavors, or a lethargic crema. The eclectic goal of espresso grinding is to achieve a compact, even bed that water can traverse in a predictable, targeted time—usually around 25 to 30 seconds for a standard shot. The portafilter, tamping pressure, and distribution all play supporting roles to the roast level. If any one component deviates, the cup will reveal it—either as a sour edge, an overly bitter finish, or a crema that stands stubbornly thin. This is why many roasters and baristas speak of a dance between roast, grind, and technique: one misstep unsettles the balance that a given roast intended to carry through extraction.

A common misconception is that espresso beans must be a special type of bean. In reality, espresso can be made with Arabica or Robusta, or with a blend of both. Robusta, with its higher caffeine content and often bolder, more forgiving crema, is a favorite in many traditional espresso blends because it can contribute body and a distinct, chocolatey or nutty note that pairs well with milk. Arabica, on the other hand, can offer brighter acidity and more nuanced fruit or floral notes, which some roasters preserve even in a dark roast to maintain complexity. The point is that the bean’s origin and species are not what designates it as “espresso.” The decision to roast darker, to grind finer, and to brew under pressure is a separate set of choices that molds the coffee into a concentrated form that works in espresso-centric drinks.

Because the espresso brew is a high-pressure, short-time process, certain flavor components that shine in drip or immersion brews may recede in an espresso shot. Bright, high-acid notes often associated with single-origin beans can become muted when the extraction is fast and forces the sugars to caramelize more rapidly. In contrast, the darker roast amplifies sweetness through caramelization and brings out roasted notes—chocolate, cacao, spice—that accompany the crema’s texture. This does not erase the bean’s origins; rather, it filters them through a different lens, a lens calibrated by heat, pressure, and time. The result is a familiar coffee experience that might feel familiar and comforting, but with a weight and intensity that drip coffee seldom matches.

The market’s habit of labeling certain beans as “espresso beans” speaks to this blending of technique and taste. The label is often a shorthand for a roast profile and grind suitable for espresso machines and for a blend designed to produce a consistent shot across a range of stores and barista skills. It is a reminder that the drink is a crafted and contextual product as much as it is a simple beverage. The beans themselves, however, remain ordinary in the sense that they could be used for any method. A light- or medium-roasted coffee can be coaxed into an espresso using a finer grind and different extraction parameters, but the result may lose the bright clarity and nuanced acidity that a lighter approach preserves in drip brewing. Conversely, a dark roast without the proper grind and tamped suppression can yield a shot that feels flat or overly burnt. The point is not that one roast type is universally better; it is that espresso, as a method, elevates a particular roast profile into a concentrated, balanced, and crema-rich experience.

For home brewers who want to understand the practical implications, it helps to imagine the espresso workflow as a calibrated system. The bean enters with a set of expectations: it has a chosen roast level that will define sweetness, body, and stability against heat. The grinder then turns the bean into a powder that water can navigate quickly and evenly. The portafilter and the tamper create a compact, uniform surface that reduces channeling. Finally, the machine applies pressure and a precise temperature, forcing water through the bed in a short window that concentrates the flavors. If you change any link in this system—roast level, grind size, or tamp pressure—the final shot’s balance shifts. It’s not that the espresso beans are different beans; it is that the system is tuned to the roast profile and the brewing method to create an espresso-specific flavor arc.

This terroir idea—about where the bean comes from and what it can offer—meets a different reality in espresso. In lighter and medium roasts used for drip or immersion brewing, terroir can glow with bright fruits, florals, and a certain vivacity that tells the story of the farm and the climate. In espresso, that story is often refracted through deeper caramel and roast notes. The origin whisper becomes a deeper murmur behind molasses sweetness and roasted chocolate. In other words, espresso emphasizes body and balance over the high notes that might be more pronounced in non-espresso methods. That is not a judgment on the origin notes’ quality; it is a commentary on how the method shapes perception. The bean’s character isn’t erased; it is recast in the context of a short, intense extraction where sensory thresholds shift under pressure.

The language of coffee is full of nuance, and the espresso parameter set is a reminder of how technique and intention shape perception. When roasters publish espresso blends, they curate a balance that, in their view, holds up to milk and heat while delivering a recognizable signature on its own. Blends often blend an element of bold sweetness with a hint of brightness, ensuring that the crema carries a lasting impression even as the drink cools. Singles origin can still appear in espresso, but the roast will often be dialed toward a profile that avoids excessive acidity and emphasizes an all-around accessibility. For many drinkers, the appeal of espresso lies in this orchestration: a compact, intense shot that remains approachable, a small beverage that feels big in aroma and body.

The bottom line for the core question remains straightforward. Espresso beans are not different species or varieties of coffee. They are coffee beans that have been selected and roasted to a darker level and prepared for a specific brewing regimen. The choice of origin—Arabica versus Robusta, single-origin versus blend—remains independent of the espresso label. What changes is how the roast’s chemistry interacts with the grind, the extraction, and the machine. This interplay defines the espresso experience: boldness balanced with smoothness, a rich crema that signals proper extraction, and a sensory profile that can stand up to milk, sugar, or simply the act of sipping the shot itself. In that sense, espresso beans are not a separate category of bean; they are a carefully tuned application of a familiar bean family.

For readers who crave more precise guidance on how to approach roast choices and their effects, the literature offers a spectrum of practical cues. If you select a dark roast for espresso, you can expect a smoother, less acidic cup with a pronounced body and a crema that clings to the sides of the cup. If you lean toward a lighter roast for espresso, you may encounter brighter acidity and more nuanced flavors that can be challenging to extract consistently under pressure, but when balanced, they reveal a lively, tea-like complexity that some drinkers prize highly. The decision hinges on what you want from the experience—an approachable, consistent shot or a coffee that foregrounds the bean’s origin note but demands careful control of grind and technique.

Ultimately, the espresso label is a practical shorthand that captures a system—the combination of roast level, grind, and extraction method—that yields a particular kind of coffee. It is a reminder that coffee is not a single, monolithic product but a family of profiles that respond to how they are roasted and prepared. The bean remains the same in its essence; the espresso badge is about how we choose to use the bean to craft an experience that is quick, powerful, and richly textured. If you’re new to espresso, begin with a dark roast and a standard grind, then observe how the shot changes as you adjust grind size and tamp pressure. If you’re more adventurous, experiment with a lighter roast to see how a more delicate acidity and aromatic brightness survive the espresso process. In both paths, the core truth persists: espresso beans are not a separate species, but a specific roasting and preparation choice that optimizes ordinary coffee beans for a distinct kind of drink.

External resource for deeper reading: CoffeeGeek: 1kg Roasted Coffee Beans Explained — Structure, Properties, and How to Implement in Industry

From Roast to Crema: Demystifying Espresso Beans and Regular Coffee Beans

The question, at first glance, seems straightforward: are espresso beans the same as regular coffee beans? The instinctive answer—yes—belongs to common sense more than to any botanical taxonomy. Yet the fuller truth runs deeper and more nuanced. The bean you put into your grinder may come from the same plant, the same species, and even the same farm, but the experience that reaches your palate depends on a chain of choices that begins with roast level and ends with the pressure of an espresso machine. In between lies a practical choreography of grind size, dose, water temperature, extraction time, and the way a shot is balanced to yield crema, sweetness, and body. The espresso ritual, then, is less about the seed’s origin and more about how that seed is treated to perform under high-pressure, fast-tiring extraction. The idea that there exists a distinct class of “espresso beans” is a marketing shorthand as much as a coffee science label. The beans themselves are not a magical species apart; they are ordinary coffee beans that have been roasted and prepared for a specific brewing method. The distinction, when you strip away the marketing gloss, is not in the plant’s lineage but in the roast trajectory and the intended water-forced immersion that defines an espresso brew.

To understand why, it helps to revisit what makes a coffee bean what it is in the first place. Coffee beans are the roasted seeds of Coffea plants, most commonly Arabica or Robusta, sometimes a blend of the two. The flavor notes—citrus, florals, chocolate, caramel, berries, spice—are the product of genetics, altitude, soil, climate, and post-harvest handling. Those are the raw materials. What follows, however, is a transformation that happens in the roaster’s chair and in the brewer’s workstation. Roast is the crucible in which origin flavors are tamed, amplified, or rearranged. A lighter roast tends to reveal delicate floral and fruity notes, preserving acidity and brightness as signposts of origin. A darker roast suppresses acidity and accentuates sweetness, body, and the resinous, almost toasty quality that many associate with espresso profiles. Those characteristics are not exclusive to “espresso beans”—they are features of a roast profile selected to match a specific brewing method.

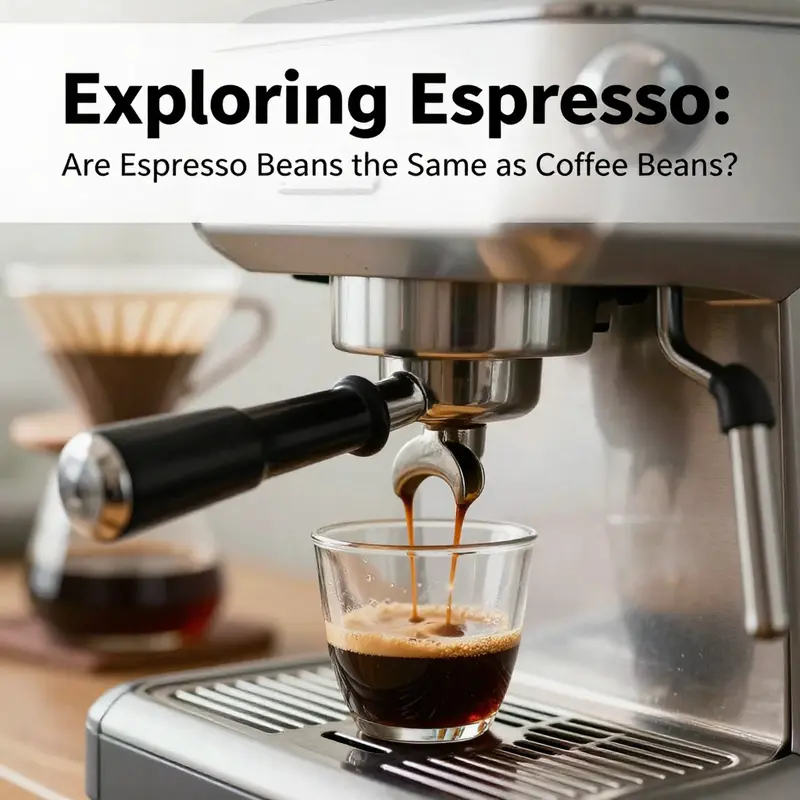

Espresso, as a brewing method, is defined by pressure, temperature, and time. An espresso machine forces hot water through finely ground coffee at high pressure, producing a concentrated shot in a relatively short span. This process extracts a core set of compounds quickly and intensely, emphasizing sweetness and body while carving away some of the expressive acidity visible in pour-over or drip brews. The result is a balance that can feel thicker and more dynamic in a single, small serving, with a velvety crema on top that signals oils and emulsified compounds rising through the pressurized flow. The grind is finer, the bed is compact, and the contact time is shorter than many other brewing methods. The overall equation—grind size plus pressure plus time—decides how the aroma compounds unfold and how the crema forms. This is where the practical difference emerges. If you take the same bean and grind it coarser for a drip machine, or use a different roast level, you will taste and feel a different beverage entirely. The bean is the same, but the alchemy of roasting and brewing has shifted the flavor axis.

The roast profile is the first and most visible dial you have as a consumer. Espresso roasts are typically darker than those used for standard drip coffee, but there is nuance beneath that generalization. Some roasters push the envelope with very dark roasts that push toward charcoal notes and a glossy, oil-slick surface. Others craft a ‘dark but balanced’ profile where sweetness emerges through chocolate and caramel notes, and acidity is kept in a friendly, forgiving range. The liver of this transformation is not only flavor but texture. Darker roasts tend to yield more body and a smoother mouthfeel, which harmonizes with the crema’s creamy, slightly viscous texture. It’s not only the taste but the sensation—the sense that the drink coats the tongue and lingers—that many espresso lovers seek. Lighter roasts, while potentially brighter and more delicate in aroma, can still make stellar espresso; they often require precise grind adjustments and perhaps a retrofitted recipe, as the high-pressure extraction will pull forward the nuances that light roasts carry. In a sense, the espresso preparation invites the drinker to chase contrast: a single shot that balances brightness with depth, or a blend designed to cushion a fruit-forward origin with the comforting sweetness of a deep roast.

Grounds and grind size play a central role in shaping how espresso beans show their character. The grind acts as a gatekeeper for extraction. In espresso, the bed of ground coffee should be compact enough to resist quick channeling, yet not so dense that water cannot permeate. A consistent, fine grind ensures even extraction; otherwise, you may end up with over-extracted, bitter patches alongside under-extracted, sour pockets. The goal is a uniform slurry that allows hot water to meet a broad surface area of coffee. The habit of tamping—pressing the grounds into a tight, level surface—adds another layer of control. If the tamp is uneven, you create channels where water rushes through, leaving behind a weak, uneven shot. When the grind is appropriate and the tamp is well executed, the shot pours with a golden crema, a sign that oils and micro-emulsified compounds are forming a harmonious emulsion under pressure.

All of this points to a practical reality: any regular coffee bean can be prepared as an espresso, provided it is roasted with an eye toward espresso extraction and ground finely enough for a high-pressure brew. The opposite is also true: a bean roasted specifically for espresso can still be used in a drip brewer, a French press, or a cold brew setup, though the resulting flavors will shift with the method. This is where the espresso bean label—often a marketing cue—meets the science of taste. Roasters who market a bean as an “espresso roast” may have selected a profile that emphasizes sweetness and body, but they are not declaring a separate species or a bean from a different plant. They are declaring a roasting and blending strategy, tempered by the way the drink will be prepared in a machine that can extract those attributes quickly and intensely.

Blends and single-origin beans offer different routes to the espresso cup. A blend can be crafted to secure a reliable crema, a consistent sweetness, and broad compatibility with milk beverages. The roaster may mix beans with complementary acidities, body, and aroma so that, when ground and fused with heat, water, and pressure, the result remains predictable across different days and machines. In contrast, a single-origin espresso aims to reveal the distinctive fingerprint of a particular region, altitude, or farm. On the one hand, a single-origin espresso can be a tour through terroir—blackberry from a high-altitude coffee, jasmine and citrus from a mineral-rich soil, or chocolate and cocoa notes from a mature bean. On the other hand, the same single-origin roast can require tighter control over roast progression and grind size to avoid sharp acidity or pale sweetness. For the beverage enthusiast, this is where the art of espresso tasting enters the dialogue: you learn to identify the origin’s innate traits within the framework of the roast, the grind, and the brew method.

The sensory landscape of espresso is a study in contrasts. The crema is not merely a garnish; it is an integral part of the overall experience. The crema’s thickness and persistence are influenced by the bean’s oil content, roast level, grind size, and the machine’s pressure profile. Espresso beans that yield a robust, long-lasting crema often contain oils that stay suspended longer under pressure. This is why many roasters highlight crema when describing a roast intended for espresso. But crema should not be mystified as the sole marker of quality. A shot with minimal crema can still carry a well-structured balance of sweetness and acidity, provided the espresso is well extracted. Conversely, a shot with an abundant crema can still taste flat if the roast is out of balance with the extraction profile. The sweetness in espresso often betrays the interplay between roast and brew: a properly roasted bean can express caramel-like sweetness, nutty notes, and soft fruit tones in harmony with the body created by the extraction process.

When thinking about whether espresso beans are the same as coffee beans, the most practical conclusion is that the beans themselves are not fundamentally different in species or origin. The differences are culinary and mechanical: roast level, grind size, and the brewing method all converge to shape the flavor, texture, and aroma of the final cup. A bean might be a mid-roast, single-origin Arabica from a mountain farm. Roasted for espresso, ground to a fine consistency, and pulled under high pressure, that same bean becomes the star of a concentrated beverage with body, sweetness, and crema that can carry a dash of milk or stand strong on its own. If you swap the roast to a lighter profile and switch to drip brewing, you might draw out an entirely different set of flavors—citrus brightness, delicate florals, or a wine-like acidity—without changing the seed’s identity.

This is not merely a footnote in coffee lore. It has practical implications for home brewers and café professionals alike. Understanding that the roast and the brew method operate as a system helps you tailor your purchases to the kind of espresso experience you want. If you crave boldness and a forgiving, milk-friendly shot, you may look for a darker roast or a carefully blended espresso blend designed to deliver consistent crema and sweetness even when the grind and machine vary a bit. If you chase clarity and distinct origin notes in your espresso, you’ll seek single-origin roasts with meticulous roasting profiles and a grinder calibrated to reveal those nuances without tipping into sourness. In both cases, the bean remains the same underlying material; the transformation is culinary engineering—the roasted profile and the machinery working in concert to coax the best from that seed.

For those who want a grounded, evidence-based path to deeper understanding, there is a wealth of resource material that explains how roast profiles affect sensory outcomes and how different extraction techniques influence flavor. A respected authority in this domain outlines how the interaction between roast level and brew method shapes acidity, sweetness, body, and aroma, and how different coffees respond to high-pressure extraction. This science emphasizes that the sensory character of espresso emerges from the sum of its parts: origin, roast, grind, dose, water quality, and the machine’s pressure dynamics. It is not a riddle about the seed alone but a coordinated act of cultivation, processing, and engineering. The takeaway is clear: espresso beans are not a separate botanical category; they are coffee beans prepared with a specific roasting and brewing intention. The label signals a recipe, not a plant taxonomy.

In practice, the espresso lover’s toolkit is a blend of curiosity and technique. Start by choosing a bean that matches your preferred flavor direction—some like the robust sweetness of a dark roast with chocolatey notes; others prefer the lively brightness of a medium or light roast that still holds up under pressure. Grind size should be fine and uniform, with reductions to accommodate different machines if you notice channeling or uneven extraction. Dose consistency and tamp pressure matter as much as the bean’s roast. Temperature stability, water hardness, and cleanliness of the machine all contribute to a balanced shot. The more you align these factors, the more you realize that the difference between espresso beans and regular coffee beans is a matter of artistic application rather than botanical designation.

To close the loop, consider the broader landscape of how we talk about beans and methods. The marketing language around “espresso beans” can be helpful for signaling a roast profile and a brewing purpose, but it should not obscure the fact that the essence of the bean remains the same. This clarity helps avoid the trap of assuming a particular roast is inherently superior for espresso. The reality is that both light and dark roasts can yield excellent espresso outcomes, depending on the drinker’s taste, the machine, and the skill with which the extraction is tuned. As with many crafts, mastering espresso involves knowing when to let a certain roast show its character and when to let the brewing method shape the perception of that character. The bean is the stage, and the roast and brew are the performance. The more fluent you become in this language, the more you appreciate that the espresso experience is not a clash of bean types but a conversation between seed, heat, pressure, and time.

For readers who want a structured, research-informed foundation, there are established guidelines and evidence-based frameworks that describe how roast progression influences sensory attributes and how extraction mechanics drive flavor balance. These resources emphasize that the science of coffee—roasting, grinding, brewing, and tasting—produces predictable patterns when properly controlled. They also remind us that the human palate remains central: the best espresso is the one that satisfies the drinker’s preferences, whether that means a velvety, milk-friendly shot or a crisp, nuanced, single-origin profile. The journey from bean to cup is a craft that invites experimentation, discipline, and curiosity, rather than a fixed dogma about what a particular label should signify.

If you want a structured map to deepen your understanding beyond personal preference, the Specialty Coffee Association provides a thorough, evidence-based perspective on roasting and brewing standards. Their guidance can illuminate why certain roast levels pair so gracefully with espresso extraction, and why precise grind and extraction control matter so much for crema and sweetness. This is not a commandment to worship at the altar of any one method; it is an invitation to explore how different roasts reveal different facets of a bean’s character when subjected to the right amount of pressure, heat, and time. In the end, the question of whether espresso beans are the same as regular coffee beans dissolves into a satisfying realization: yes, they are the same beans, and the artistry lies in how you treat them to unleash the spectrum of flavor known as espresso.

External resource: For a deeper, science-based exploration of roast profiles and extraction, consult the Specialty Coffee Association at https://sca.coffee.

null

null

Final thoughts

Understanding the distinctions between espresso beans and regular coffee beans not only enriches your appreciation for quality coffee but directly impacts your business’s product offerings. Recognizing the nuances of roast levels, brewing methods, and grind sizes can lead to enhanced customer satisfaction and potential growth in sales. Embrace these insights to elevate your coffee repertoire and stand out in the competitive market.