Understanding the right occupational therapy equipment is pivotal for business owners involved in therapy practices. This article delves into various categories of tools that are indispensable in supporting clients’ recovery and skill development. Through this exploration, business owners will gain insights into vital equipment that enhances fine motor skills, gross motor functions, sensory integration, and cognitive training, ultimately creating a well-rounded therapy program for their clientele.

Fine Motor Foundations: How Fine-Motor Tools Shape the Occupational Therapy Equipment List

Fine motor skill development is the quiet backbone of functional independence. In occupational therapy, it is not enough to aim for movement alone; clinicians design and deploy a carefully chosen set of tools that cultivate precise finger control, robust hand strength, and coordinated movement. When therapists assemble an equipment list, they think in terms of a language of small, deliberate actions—pinching, grasping, manipulating, and releasing—that cumulatively unlock daily tasks such as dressing, writing, feeding, and personal care. The chapter you are reading delves into how a well-curated suite of fine motor tools translates into meaningful outcomes. It also reveals how equipment choices are tailored to the client’s age, diagnosis, and stage of recovery, while remaining consistent with established practice standards. In the broader arc of an OT program, these tools are not mere gadgets; they are practice-based instruments that guide therapy toward measurable gains in dexterity and independence, while also shaping the client’s confidence to engage in activities that matter to them most.

At the core of these tools is a simple premise: small, progressively challenging tasks build resilient motor patterns. Therapists begin with tasks that invite a safe, controlled attempt at movement, then gradually increase complexity as control emerges. This approach mirrors the way a child learns to write, buttons a shirt, or manage utensils. The equipment list for fine motor development includes a spectrum of options designed to target specific facets of dexterity. In one section, practitioners rely on manipulatives that isolate finger movements; in another, they incorporate tools that promote bimanual coordination and integration of symmetry across both hands. The aim is not to overwhelm but to scaffold, guiding the hand from exploration to skilled execution.

One foundational category centers on resistance and strengthening. Therapy putty and similar resistance materials offer multiple advantages beyond raw strength. They invite multi-directional fingers to bend, twist, and stretch, engaging the palmar arches, intrinsic hand muscles, and the pincer and tripod grasp patterns that underlie precision. The resistive continuum—soft, medium, and hard—allows progressions tailored to the client’s muscle tone, endurance, and comfort. For a child with developing dexterity, the act of squeezing and releasing putty translates into smoother transitions when gripping a pencil or holding a small object. For an adult recovering from injury, the same materials can retrain the subtle timing of finger flexion and extension essential for controlled handwriting or precise tool use. These tools remind us that strength and coordination are learned in the context of purposeful tasks, not in isolated muscle exercises.

Equally important are tools that train fine motor control in isolation and in tandem. Pegboards and pegs, for example, are classic measures of precise finger movements. The task of selecting a peg, grasping it with a stable tripod grasp, and guiding it into a hole requires finger isolation, eye-hand coordination, and bilateral coordination when performed with two hands. The repetitive nature of pegboard work helps establish reliable finger trajectories and reduces tremor or clumsy grips that can hamper daily tasks. When a child progresses from large to small pegs, from single-hand to two-handed manipulation, the activity maps onto increasingly complex tasks such as buttoning, lacing, or manipulating small fasteners on clothing. The same principles apply to adults relearning tool use after an injury, where repeated, graded practice yields smoother, more consistent performance.

To translate those skills into everyday life, therapists incorporate dressing boards, buttoning boards, and lacing cards. These tools simulate real-life dressing tasks, enabling clients to practice finger isolation, sequencing, and visual-motor integration in a safe, controlled environment. A child who can complete a small buttoning task on a practice board is gradually primed to dress independently at home. The sequencing demands—aligning fabric edges, positioning the button, and coordinating the opposite hand to secure front closures—build executive function and motor planning as well. Lacing cards extend the same logic to bilateral coordination and precision. The child threads a lace through a series of holes, coordinating finger movements with hand-eye alignment while maintaining posture and forearm stability. These activities seem modest, yet they form the granular steps that culminate in confident self-care and school readiness.

Tongs and tweezers provide another essential bridge between play and real-world function. Grasping tiny items, such as beads or pom-poms, with a tripod grip fosters precision and restraint in finger movements. The practice supports fine motor control necessary for penmanship, cutting with scissors, or manipulating small objects on a desktop or kitchen counter. In therapy, these tools often serve as a prelude to more complex tasks, including manipulating fasteners, manipulating small construction pieces, or assembling a small object with multiple components. As with other fine motor activities, the complexity of the task can be adjusted—changing the size of the objects, the distance between items, or the required speed of placement—to match the client’s growth. The underlying goal is not speed but accuracy and control, which in turn reduces frustration and builds confidence.

Another cornerstone of fine motor work lies in sensory-rich play that engages tactile discrimination and proprioceptive feedback. Sensory bins filled with rice, beans, or sand create a forgiving landscape where scooping, pouring, and retrieving small items become opportunities to refine grasp patterns and hand alignment. The tactile variety challenges the fingers to differentiate textures and resistive forces, which supports spatial awareness and effective hand positioning during more precise tasks. Sensory-motor integration is not an optional add-on; it is a crucial lens through which therapists interpret the client’s responsiveness to touch, pressure, and temperature, all of which influence grip and release. When a child learns to modulate grip based on the material’s resistance, they carry that modulation into writing, drawing, and tool use. The bins also function as a motivational platform, inviting curiosity and sustained engagement, which are essential for repetition and mastery.

Writing and tracing tools cap this suite with a focus on form, posture, and legibility. Specialized pencils, adaptive grips, and tracing boards address both the mechanics of handwriting and the broader demands of classroom tasks. A well-designed grip reduces fatigue and promotes a neutral wrist posture, while tracing activities support letter formation, motor memory, and kinesthetic awareness. For many clients, the transition from using simple writing tools to more complex tasks—such as taking notes or completing written assignments—depends on the quality of grip support and the stability of the arm and shoulder during writing. These tools are deliberately varied to accommodate different hand sizes, strength levels, and motor control profiles, ensuring that progress remains accessible across ages and abilities.

Adaptive utensils and cutlery extend the same philosophy to feeding and self-care. Built-up handles, larger grips, and modified shapes reduce the cognitive and physical load required to hold utensils effectively. The goal here is not to simplify the task but to promote efficient grip patterns that minimize strain and maximize control. In a therapeutic session, practicing with adaptive cutlery translates into improved self-feeding independence at home or school. The broader implication is that small adjustments to tool design can unlock a cascade of improvements in daily routines, from opening a jar to cutting meat or spreading butter. The equipment list thus interlocks with ADLs, reinforcing a holistic view of the client’s capabilities and the daily environments in which they operate.

Durability and technique are the practical underpinnings of all these tools. The literature and field experience converge on a single message: equipment must withstand frequent use and be used with proper technique to prevent strain. This is especially true in pediatric settings where equipment may be manipulated with vigor and by varied levels of coordination, as well as in adult rehabilitation where repetitive practice is common. Therapists routinely assess wear, clean and sanitize materials, and prescribe replacements when necessary. The equipment list is not static; it evolves with the client’s progress and with advances in practice guidelines. As of early 2026, durability remains a critical consideration, along with the emphasis on safe handling and the alignment of tool properties with therapeutic goals. A well-curated inventory empowers clinicians to adapt to diverse clinical contexts—from community clinics to schools to acute care—without compromising safety or efficacy.

In crafting a coherent fine motor program, therapists integrate the above tools into a narrative that resembles a carefully woven thread. Each element—putty for strength, pegboards for precision, buttoning boards for sequencing, tongs for control, sensory bins for tactile feedback, tracing and writing tools for handwriting, and adaptive utensils for daily living—contributes a distinct thread of practice. The fabric that emerges is a plan that is both individually tailored and broadly evidence-informed. This means the therapist continuously observes, measures progress, and recalibrates tasks to maintain engagement while ensuring that the client can transfer skills from the clinic into home, school, or work. In other words, the equipment list becomes a dynamic map rather than a fixed catalog, guiding the journey from exploration to independence.

For clinicians and students seeking a concise synthesis of how to match tools with outcomes, one can conceptualize this: early tasks build strength and stability; mid-level tasks refine precision and coordination; advanced tasks translate into fluid, efficient performance in daily life. The practitioner’s judgment—grounded in training, observation, and evidence-based guidelines—determines the sequencing, pacing, and context for each tool. It is a craft that requires patience, reflection, and a willingness to adjust to the subtle shifts in a client’s abilities and motivation. The result is not merely improved dexterity but greater autonomy, confidence, and participation in the life activities that matter most to the person.

To deepen understanding of how clinicians select and integrate equipment, consider a practical guide on tools and equipment for occupational therapists. This resource offers a structured view of standards, performance, and practical applications that can inform daily practice in any setting. tools and equipment for occupational therapists.

As a concluding note, the alignment between the fine motor toolset and the client’s goals is what grants therapy its transformative power. A well-conceived equipment list acts as both canvas and toolkit, allowing therapists to paint a map of achievable milestones and to celebrate the small, steady steps that culminate in meaningful independence. The devices and activities described here are not ends in themselves but means to an end: a life with increased autonomy, dignity, and participation in everyday activities. The equipment list, when applied with care, reinforces a client-centered narrative in which every pinch, grasp, and release brings a person closer to the daily routines they want to own. The result is more than improved dexterity; it is a reinforced sense of self-efficacy that travels beyond the therapy room and into the heart of everyday life.

External reference: For a broader overview of standards, performance, and practical applications of occupational therapy equipment in contemporary practice, see https://www.therapysupply.com/blog/occupational-therapy-equipment-guide

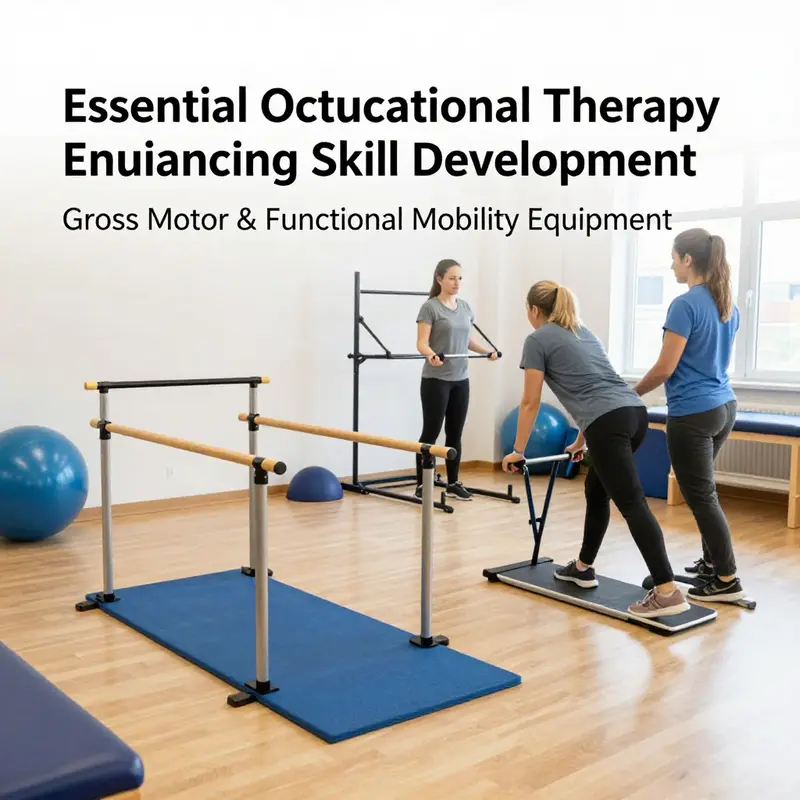

Stepping Forward: The Role of Gross Motor and Functional Mobility Equipment in Occupational Therapy Practice

Movement is more than a sequence of steps; it is a gateway to independence in daily life. In occupational therapy, gross motor and functional mobility equipment acts as the bridge between intention and action. Therapists select, arrange, and tailor tools so that a person can move with greater confidence, balance, and efficiency—from the first tentative weight shift to a confident, purposeful walk across a room. The equipment used in this domain is a carefully chosen, progressively challenging toolkit that supports not only biomechanics but the mind’s willingness to engage with activity, conserve energy, and take risks safely. The ultimate aim is participation: to enable a client to navigate home, work, school, and the community with less fatigue and fewer safety concerns.

The starting point for any equipment plan is a patient-centered assessment that respects both the body and the environment. Clinicians observe symmetry, endurance, tone, reflex patterns, and postural control while the person stands, moves, and transitions between positions. The assessment also considers the living situation, typical routes through the home or workplace, and the level of supervision available. Clear goals emerge from this, such as improving sit-to-stand efficiency, extending walking tolerance, or enabling safer transfers. Once goals are defined, the therapist weighs the range of devices that can scaffold movement and progressively reduce support as strengths develop. Durability, safety, ease of use, and compatibility with the person’s weight and size are as important as the clinical effect of any device.

Within this framework, gait trainers and standing frames serve distinct but complementary roles. Gait trainers provide stability and guided movement when weight-bearing or step initiation is challenging. They help rebuild the neuromuscular patterns necessary for walking, offering adjustable height, varied support levels, and a secure frame that patients can lean into. Standing frames address upright postural alignment and the systemic benefits of weight-bearing, including improved circulation, bone density, and sensory integration. When used together, these tools allow therapists to choreograph a progression—from supported movement with a gait trainer to upright tolerance with a standing frame, and onward toward assisted ambulation with reduced external support.

Balance and core stability are central to functional mobility, and therapy balls, wobble boards, and balance cushions provide essential challenges that translate into everyday competence. An unstable surface compels the body to recruit deep stabilizers and refine weight-shift strategies. The therapist calibrates difficulty, starting with familiar tasks like seated reaching or static standing, then advancing to dynamic activities such as reaching, stepping in place, or light weight shifts with the pelvis. Proprioceptive and vestibular inputs from these tools can enhance self awareness of posture and movement quality. A well-structured sequence begins with a stable base of support, progresses to a balance board, and may incorporate a therapy ball in sit-to-stand practice or stepping tasks.

Parallel bars and other supported ambulation setups illustrate how therapists cultivate independence while maintaining safety. Parallel bars provide a robust yet adjustable scaffold for early gait training, enabling clients to practice leg and trunk coordination with reduced risk of falls. As confidence grows, therapists introduce more variability—altering bar height, adding manual cues, or integrating functional tasks like turning, stepping over obstacles, or transitioning to a more open environment. The strategic use of parallel bars is not about prolonging dependence but about shaping motor learning in a controlled, measurable way toward dynamic, real world movement.

Mobility devices such as wheelchairs or power assisted movement are integral when lower limb function is limited or when fatigue limits engagement. The emphasis in OT is on enabling choice and participation while safeguarding health and safety. A well thought plan might begin with a wheelchair for essential access, followed by focused interventions to promote transfers, posture, and trunk control that reduce secondary complications. Durable equipment that supports posture, such as seating systems with appropriate back supports or cushions, protects joints and reduces pain, thereby making community participation feasible rather than a barrier. The aim is not merely to move from point A to point B but to shape the quality of movement and the ease with which a person can engage in desired activities, from cooking and dressing to community navigation.

Environment-specific adaptations and task oriented training extend the benefits of mobility work beyond the clinic. Transfer boards and slide boards facilitate safe transitions between surfaces, while walking sticks or canes provide a progressive step toward autonomy as balance improves. The clinician emphasizes safe transfer techniques, proper body mechanics, and caregiver training to sustain gains between sessions. The broader goal remains: to expand the person’s participation in meaningful activities while maintaining safety, comfort, and energy efficiency in daily life.

Durability and maintenance emerge as central themes in clinical practice. Regular inspections, timely repairs, and a structured maintenance routine protect users from equipment failure and support long term progress. Clinicians rely on evidence based guidelines, adapt to different settings, and continuously align equipment choices with the person’s evolving goals. When devices are reliable and well maintained, the focus shifts to movement quality, goal attainment, and the joy of participation in activities that matter to the person. In this way, gross motor and functional mobility tools become the enabling chapters that unlock participation in the occupations people care about most.

Sensing Healing: How Sensory Integration Tools Shape the Occupational Therapy Equipment Arsenal

Sensory integration sits at the heart of many occupational therapy plans, acting as a bridge between sensation and function. Therapists use tools that help the nervous system organize incoming information, regulate arousal, and support adaptive responses to daily life. When crafted into a thoughtful equipment list, these tools become more than toys or fidgets; they are instruments that open pathways to attention, self-regulation, motor control, and engagement in meaningful activities. The sensory toolkit is not a static catalog. It evolves with research, clinical observations, and the lived experiences of clients across ages and diagnoses. In practice, it is a carefully sequenced, play-infused approach that respects each person’s sensory history while offering safe, predictable opportunities to practice processing and modulation in real time. The result is not merely calmer moments in therapy but transferable skills that carry into classrooms, homes, and community settings. Within the broader occupational therapy equipment list, sensory integration tools occupy a pivotal position because they touch multiple domains: tactile discrimination, proprioception, vestibular processing, and coordinated movement. They also address a core barrier observed in many pediatric and developmental populations: the challenge of integrating multiple sensory streams into coordinated action. A weighted blanket may provide a sense of containment and predictability; a textured board invites tactile exploration; a vibration toy offers intermittent proprioceptive feedback; a sensory bin becomes a small world where curiosity and regulation intersect. Each item, chosen with intention, supports a child or adult as they learn to modulate their body’s responses to the world around them. The clinical rationale behind selecting sensory tools begins with a clear understanding of each person’s sensory profile. Some children crave heavy input to feel organized; others seek light, variable stimuli to stay alert without becoming overwhelmed. Therapists document sensory preferences and thresholds, then tailor the equipment mix accordingly. The goal is not to overwhelm or over-stimulate but to provide just-right challenges that invite active participation. In this sense, the sensory integration toolkit resembles a musician’s instrument case. Each tool offers a unique timbre and tempo, and the therapist carefully orchestrates how and when to deploy them to meet specific therapeutic aims. A session might begin with a calm, grounding activity to set the nervous system and gradually move toward tasks that require fine motor control or problem-solving. In such a flow, the equipment list becomes a narrative device, guiding transitions from vestibular orienting activities to tactile exploration to purposeful movement. Consider weighted blankets and vests as anchors in a session. The deep pressure they provide can help reduce autonomic overactivity and improve body awareness. For some clients, a short time under weighted input can lower the baseline arousal level, making subsequent tasks more approachable. The therapist watches for cues—changes in breathing, muscle tone, or eye contact—that signal readiness to progress or a need to pause. The decision to use a weighted item is dynamic and individualized, never prescriptive. Textured sensory boards then offer a tactile map of the body’s interaction with different textures, patterns, and resistances. Varied surfaces invite finger exploration, pushing and pulling motions, and precision handling. These boards are not mere curiosities; they are strategic tools to develop tactile discrimination, fine motor control, and hand-eye coordination. A child who differentiates rough from smooth textures may later apply this discrimination to more complex tasks, like dressing, feeding, or manipulating small objects with confidence. Proprioceptive input devices, including vibration toys and proprioceptive-rich fidgets, serve a complementary role. They provide bodily feedback that can recalibrate the nervous system during moments of overwhelm or restlessness. Gentle vibration, rhythmic pressing, or controlled squeezing helps the learner modulate their sensory state, then return to tasks with better attention and steadier movement. Sensory bins offer a broader, exploratory modality. Filled with rice, beans, kinetic sand, or other safe materials, bins engage the senses through touch, sight, and sometimes sound. They create a sandbox for practicing coarse and fine motor skills, sequencing, and imaginative play while fostering sustained attention. In teaching terms, sensory bins also become transparent assessment tools. A therapist observes how a client investigates a new material, how they bring hands to the task, how they manage mess, and how they adapt their approach when tools or materials are altered. Therapy putty and other resistive hand tools provide low- to moderate-load opportunities to strengthen intrinsic hand muscles, facilitate precision grip, and build endurance. A therapist might guide a client to pinch, flatten, roll, or manipulate putty while simultaneously prompting eye-hand coordination and carryover to handwriting, scissor use, and buttoning. The sensory toolkit is never static. Therapists rotate and combine elements to sustain engagement and target evolving goals. Interactive developmental toys with multisensory feedback—visual cues, sounds, touch, and motion—offer motivation while integrating sensory processing with cognitive and motor demands. These toys are designed to scaffold attention, encourage cause-and-effect learning, and support social interaction in turn-taking and communication. The beauty of these tools lies in their play-based foundation. Children often learn best through games they already enjoy, and sensory-integrative play aligns naturally with engagement, perseverance, and resilience. Yet it is essential to recognize that not all play is therapeutic by itself. The intervention requires careful observation, measurement, and adjustment. A successful sensory program blends structured activities with opportunities for spontaneous exploration. In this light, the equipment list becomes a dynamic curriculum. It supports not only individual goals but also collaborative practice with families, teachers, and other healthcare professionals. The family’s daily environment is a critical arena for extending what happens in the therapy room. When quiet routines, predictable materials, and gentle sensory challenges saturate home life, progress becomes more durable. Therapists guide families to select materials compatible with home spaces, maintain safety standards, and integrate sensory strategies into everyday routines. For example, a parent might incorporate a weighted blanket during quiet reading periods or use a small sensory bin as a calm-down station after school. The equipment list thus serves as a bridge between clinical practice and real-world function, ensuring that gains in regulation, attention, and motor skills translate into tangible activities of daily living. The selection of sensory tools is influenced by broader occupational therapy guidelines and evidence-based practice. Practitioners consult professional standards to determine which tools align with safety, efficacy, and ethical use. The American Occupational Therapy Association provides practice resources that help clinicians choose tools that meet rigorous criteria for safety and effectiveness. Those resources underscore the importance of using evidence-informed strategies and ongoing assessment to refine equipment choices. Within this framework, durability and proper use become central considerations. Many sensory tools are used repeatedly and must endure active handling, cleaning, and occasional rough play. Materials should be hypoallergenic, washable where possible, and free from small parts that could pose choking hazards for younger clients. This is especially critical for younger children or individuals who manipulate objects with intense force. Durability is not just about the product’s lifespan; it is about the tool’s ability to sustain consistent clinical outcomes without breaking down or altering sensory feedback in ways that could mislead or hinder progress. In some regions, the manufacturing landscape supports these demands through specialized hubs. Writers and clinicians often look to producers in locations known for textile-based sensory items or other durable materials. Such regional specialization can influence the availability of washable textures, colorfast fabrics, and safe, soft plastics that stand up to frequent cleaning and disinfection. When selecting suppliers, therapists weigh factors like material safety data sheets, washability, and ease of sanitation, alongside cost and lead times. Even the most robust tool must be incorporated into a structured plan. A well-designed sensory program uses these items as part of a larger intervention sequence that addresses goals across motor, cognitive, and social domains. For instance, a session might begin with a vestibular activation activity to prime the state system, followed by tactile discrimination tasks using textured boards. Next, proprioceptive or heavy work activities could be integrated to support a stable foundation for fine motor tasks like cutting, buttoning, or handwriting. Throughout, therapists embed reminders about safety, positioning, and appropriate supervision to ensure a calm, productive environment. The care pathway also involves careful documentation. Clinicians record which tools were used, for how long, and what responses or progress were observed. This ongoing data collection informs adjustments to the equipment mix and session structure. It can reveal patterns, such as which textures consistently elicit calm engagement or which activities produce the most improvement in posture and reach. In addition to clinical practice, sourcing sensory integration tools becomes a strategic decision for facilities. Reputable manufacturers in specialized regions focus on producing washable, hypoallergenic, and durable items designed for clinical use. Collaboration with such suppliers supports long-term program sustainability and helps ensure safety and efficacy. The broader equipment list gains depth through these tools, reinforcing the idea that sensory integration is not an add-on but an integral part of a comprehensive OT strategy. For healthcare providers, rehabilitation centers, and educational settings seeking reliable suppliers, a complete guide emphasizes not only what tools exist but how to evaluate them for safety, efficacy, and practicality. An extended resource highlights standards, performance, and practical applications across a spectrum of OT contexts. This literature also notes that ongoing research, professional development, and cross-disciplinary collaboration are essential to keep practice current and responsive to emerging needs. It reminds practitioners to view sensory tools as dynamic elements that adapt to each client’s evolving profile rather than fixed assets. For those exploring how sensory strategies integrate with specific conditions, the literature on autism and sensory processing disorders offers practical insights. In ASD care, sensory integration tools support regulation, attention, and participation in daily activities, while respecting the diverse sensory preferences within the spectrum. Practitioners often tailor tool choices to individual sensory profiles and to family routines, ensuring that the strategy remains feasible and sustainable. If you want to delve into these connections, consider exploring resources that discuss autism-focused approaches and how they intersect with activity demands and environmental supports. occupational therapy for autism provides a useful overview of how sensory strategies align with developmental goals and daily routines. This integration of theory, practice, and home application helps ensure that the sensory toolkit supports meaningful change beyond the therapy room. When considering sourcing and implementation, it is also useful to reference external guidance that consolidates current practice guidelines. A comprehensive OT equipment guide published in late 2025 highlights the role of sensory integration tools within the wider equipment list, detailing assessment procedures, material considerations, and implementation strategies. The guide emphasizes how clinicians balance evidence with clinical judgment to select tools that meet diverse client needs while maintaining safety and efficiency in busy clinical settings. The chapter’s emphasis on sensory integration tools is not meant to overshadow other OT equipment categories. Instead, it illustrates how these tools interlock with fine motor development aids, gross motor supports, cognitive and perceptual training devices, and activities of daily living aids. The objective is to create a cohesive, client-centered practice where every piece of equipment contributes to a holistic growth arc. In sum, sensory integration tools are a cornerstone of the occupational therapy equipment list because they address fundamental neural regulation mechanisms that underlie learning and participation. They offer a flexible, evidence-informed pathway for improving attention, emotional regulation, and motor coordination through playful, purposeful activities. As therapists observe how clients respond to texture, pressure, motion, and weight, they learn to fine-tune the environment, the materials, and the sequencing of tasks. The result is a therapy experience that feels intimate and responsive while delivering durable, transferable gains in daily living. For readers seeking practical guidance, the following resources provide both theoretical framing and actionable recommendations, helping to bridge clinical expertise with real-world application. External resource: https://www.therapysupply.com/insights/occupational-therapy-equipment-guide. This article offers a comprehensive, evidence-based lens on equipment selection, including sensory integration considerations, and can serve as a stepping stone for clinicians refining their own sensory toolkits. As the field continues to evolve, the sensory integration toolkit will remain a dynamic centerpiece of the occupational therapy equipment list—an evolving language through which therapists help clients sense, adapt, and thrive in the world around them.

Cognitive and Perceptual Training Tools: Mapping Meaningful Minds onto the Occupational Therapy Equipment List

Cognitive and perceptual training equipment sits at a pivotal crossroads in the occupational therapy toolkit. It is where mental processes—the attention that keeps a task on track, the memory that guides steps through a sequence, the problem-solving mind that adjusts plans on the fly, and the visual-spatial system that helps us orient objects in space—meet the tangible, hands-on world of therapy. This chapter treats these tools not as isolated gadgets but as active partners in living. They are chosen and arranged with the same care that a therapist uses when selecting activities for a patient’s daily life, because the ultimate aim is not to test a skill in abstraction but to scaffold a person toward functional independence. In practice, cognitive and perceptual training equipment can range from simple, low-tech materials that invite immediate, tangible manipulation to sophisticated digital platforms that adapt in real time to a client’s evolving abilities. Yet regardless of complexity, the most effective use of these tools always draws a clear line to real-world tasks, ensuring that gains in the clinic translate into smoother performance at home, at work, or in the community. This is where the wisdom of professional organizations, such as the American Occupational Therapy Association, informs daily practice. Their guidelines emphasize task-specific, goal-oriented activities that are tailored to an individual’s functional needs, a reminder that cognitive work is most powerful when it is meaningful and directly connected to daily routines. For practitioners seeking a compact path through the landscape of cognitive and perceptual training, a practical touchstone is to consider the function each tool serves and the everyday context in which the client operates. In this light, the equipment list for cognitive and perceptual training becomes less about cataloging items and more about mapping a client’s cognitive ecology—attention, memory, executive function, perception, and visuospatial skills—onto a sequence of purposeful tasks that resemble the activities the person cares about in life. The starting point is often a simple, engaged prompt: a puzzle that requires sustained focus, a memory game that sequences events in a familiar process, or a visual tracking exercise that mirrors the way a client reads a room for safety. The beauty of cognitive and perceptual tools lies in their adaptability. Low-tech options such as memory games, pattern matching, and sequencing tasks can be modulated by changing the complexity of the steps, the speed of presentation, or the size of the materials. For clients emerging from brain injury or a neurological condition, this adjustability is essential. It allows therapists to calibrate the task to match the person’s current processing speed and gradually increase demand as competence grows, a stepwise climb that respects fatigue and cognitive load while preserving motivation. In the same breath, high-tech solutions—digital platforms and adaptive software that offer immediate feedback and scalable difficulty—are not a replacement for human judgment but a powerful complement. These platforms can present tasks that blend memory, attention, and executive function within ecologically valid contexts. They can also provide objective data about response times, accuracy, and progression, helping therapists fine-tune interventions with precision. Yet the aim remains the same: to engage cognitive systems in ways that resemble real-life challenges. A robust cognitive training session might begin with a brief, goal-oriented assessment of current abilities, followed by tasks that elicit specific cognitive processes. For example, a session could identify a client who struggles with sustained attention during household chores and then introduce a sequence-based task that mirrors multi-step cooking or cleaning routines. The equipment used—ranging from memory boards and visual scanning activities to timed sequencing tasks and adaptive cognitive software—should be selected not merely for its novelty but for its potential to cultivate functional persistence and task initiation. In this sense, the cognitive and perceptual toolbox operates through a triad of components: engagement, challenge, and feedback. Engagement is fostered when tasks resemble meaningful activities and when the client understands the purpose behind each activity. Challenge is built by gradually increasing demands—lengthening sequences, reducing cues, or introducing competing stimuli—so that cognitive systems expand capability without collapsing under overload. Feedback, whether intrinsic or augmented, reinforces learning by signaling progress and guiding error correction. Throughout this process, the clinician remains vigilant about safety, especially when tasks involve visually guided actions or risk-prone sequences. The equipment itself must be durable, user-friendly, and adaptable to different settings, from clinics to homes, to ensure continuity of practice. The longevity of cognitive tools is enhanced by design elements that accommodate various levels of cognitive demand, such as adjustable timers, variable task lengths, and modular activities that can be reconfigured to suit evolving goals. A well-curated cognitive and perceptual training arm therefore presents a spectrum—from tactile, hands-on activities like sorting and matching to interactive digital experiences that reward incremental mastery. The simplest exercises can serve as foundational scaffolds for more complex tasks. A memory game, for instance, can be extended into a routine that involves planning, organization, and self-checking strategies, thereby bridging short-term memory with executive functioning. The practitioner’s role is not to prescribe a single pathway but to illuminate several viable routes and then collaborate with the client to select the path that feels most accessible and meaningful. In this process, the alignment with daily life is central. Activities are chosen not for their intrinsic difficulty but for their capacity to evoke the tasks clients want to perform—getting ready in the morning, following a recipe, managing a shopping list, or navigating a transit route. The cognitive tasks are embedded within contexts that approximate those real-world situations, making the therapy feel purposeful and empowering rather than abstract or clinical. An important aspect of this approach is the integration of cognitive and perceptual training with activities of daily living (ADLs). When cognitive demands are tethered to practical tasks, clients experience visible, transferable gains. A client working on planning and sequencing might practice with a kitchen task that requires following a recipe, measuring ingredients, and timing steps to prevent a burned dish. This kind of integrated practice demonstrates to clients that cognitive improvement has concrete, everyday value, which in turn strengthens motivation and adherence to treatment plans. For therapists seeking to deepen the impact of these tools, the literature supports a strategy that blends task-specific training with environmental adaptations. The environmental context in which cognitive tasks occur can either facilitate or hinder success. Subtle adjustments—reducing clutter, establishing consistent routines, or providing external reminders—can complement cognitive drills and help clients apply new skills in familiar settings. The goal is to cultivate a durable cognitive habit that outlasts the therapy session itself. In practice, this means selecting and sequencing tools to reflect a client’s priorities and current life demands. A client with attention deficits might benefit from a structured routine that interleaves short, varied activities, each clearly cued and time-bound. A client with visuospatial challenges could work on visual pursuit and figure-ground discrimination through pattern-matching exercises that progressively increase complexity, followed by a real-world task such as organizing a bookshelf or navigating a cluttered room with a clear plan. The choice of equipment is therefore less about the novelty of the device and more about its capacity to illuminate a functional goal. The most effective cognitive and perceptual training programs are those that remain flexible, evidence-informed, and client-centered. They require ongoing assessment and adjustment, with progress documented through observable improvements in daily functioning rather than isolated test scores. When integrated thoughtfully, cognitive tools become something more than a set of boxes on a shelf; they become instruments that help people reclaim autonomy, reestablish confidence, and reframe what is possible in the face of cognitive or perceptual limits. For readers seeking deeper context about how these tools fit into evidence-based practice, the field’s guidelines emphasize that cognitive training should be task-specific and goal-oriented, tailored to functional needs, and aligned with the individual’s daily life. To explore further, you can consult authoritative resources such as the official occupational therapy guidelines by the American Occupational Therapy Association. See the AOTA Official Website for a detailed overview of current evidence-based practices in cognitive and perceptual training. To connect this guide with more practical examples and personal narratives, consider the insights available at the blog post on cognitive activities for adults in occupational therapy Cognitive activities for adults in occupational therapy. This resource helps illuminate how clinicians translate theory into routine tasks that people actually perform every day. In sum, cognitive and perceptual training equipment is most valuable when it helps a client move from isolated cognitive tasks to integrated daily life, bridging the gap between what the brain can do in a clinic and what a person can do at home, at work, and in the community. The equipment list becomes a living map of that journey, guiding therapists toward practices that respect the person’s goals while harnessing the full potential of cognitive and perceptual growth. For a broader perspective on professional guidelines and best practices in this domain, refer to the official guidance from the field’s governing body at https://www.aota.org/. External resource: https://www.aota.org/.

Final thoughts

Incorporating the right occupational therapy equipment is essential for optimizing client outcomes. By understanding and investing in tools for fine motor skill development, gross motor and functional mobility, sensory integration, and cognitive training, business owners can enhance their therapy services. This equipment not only benefits clients but also establishes your practice as a proactive leader in rehabilitation and therapy. Selecting tools that align with therapeutic goals translates into improved performance and client satisfaction, creating a more effective therapy environment.