Stroke recovery is a complex process, often fraught with challenges that can impede an individual’s ability to perform daily tasks. In this context, Occupational Therapy (OT) emerges as a crucial component in rehabilitation, focusing on restoring motor control, enhancing cognitive functions, and facilitating social integration. Through evidence-based interventions tailored to individual needs, occupational therapists guide stroke survivors towards greater independence and improved quality of life. This article delves into five key aspects of how occupational therapy supports recovery: enhancing motor control and hand function, utilizing evidence-based interventions, modifying the environment for safety and accessibility, cognitive rehabilitation strategies, and bolstering psychological well-being and social reintegration. Each chapter highlights the integral role that occupational therapy plays in helping individuals reclaim their daily lives, ultimately fostering resilience and recovery.

Rewiring Daily Life: How Occupational Therapy Rebuilds Motor Control and Hand Function After Stroke

A stroke does not end a person’s story; it often marks the start of a careful, patient-driven process of rebuilding the everyday. Occupational therapy (OT) sits at the intersection of body, mind, and living space, guiding people toward renewed independence in tasks that once felt automatic. The focus is not only on moving a hand or a finger but on reestablishing the capacity to dress, eat, write, and care for oneself with confidence. In the aftermath of a stroke, many survivors contend with weakness, reduced coordination, and slower speed of movement in the affected upper limb. These impairments can disrupt simple acts like buttoning a shirt, turning a page, or lifting a mug. OT views these challenges through a practical lens: how can movement become reliable, efficient, and meaningful again in daily life? The best answers come from strategies grounded in neuroplasticity—the nervous system’s ability to reorganize itself in response to purposeful practice and problem-solving. By pairing goal-driven tasks with careful assessment and adaptation, occupational therapists help patients translate small gains into durable, everyday independence.

A cornerstone of this work is task-based motor control intervention. Rather than isolating a single joint or muscle, therapists design activities that resemble real life and require the integration of multiple movements. The patient might practice reaching for objects of varying size, grasping and manipulating small items like buttons or coins, turning pages in a book, or using utensils during meal preparation. Each activity is selected to be purposeful and motivating, with the patient’s own goals guiding the choice of tasks. Repetition in a functional context is essential because it strengthens not just a sequence of actions but the whole pattern of coordinated movement that underpins daily tasks. Through repeated practice, the brain updates its maps of how to move, fostering improved motor control and more fluid hand function. In evaluating progress, therapists look beyond raw strength to how well the person can initiate, sequence, and adapt movements to accomplish ordinary tasks under realistic conditions. For a practical overview of how these exercises look in daily life, see occupational-therapy-exercises-for-stroke.

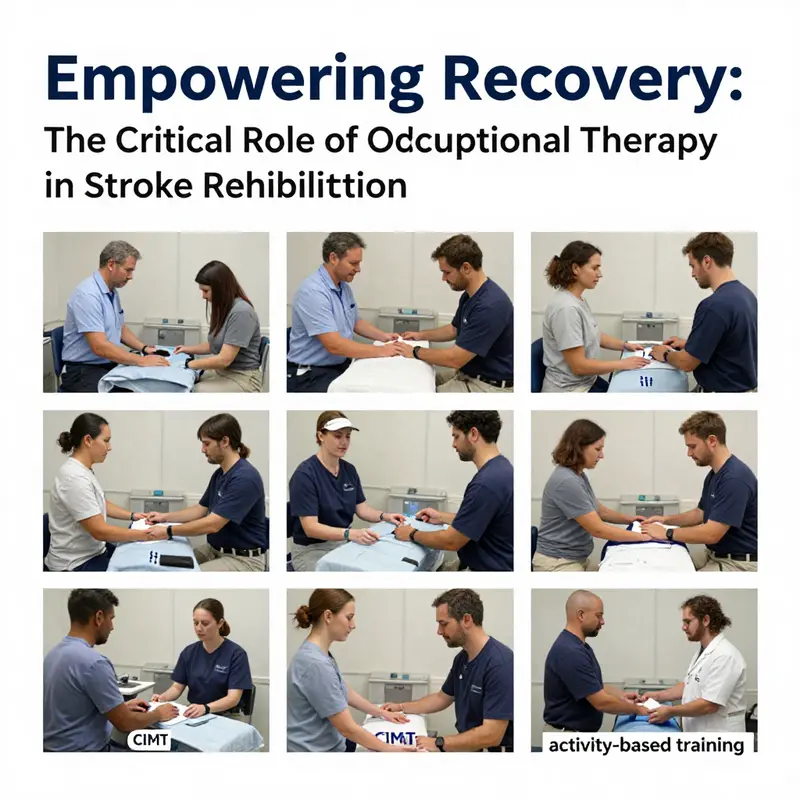

Among the most powerful tools within OT is constraint-induced movement therapy, or CIMT, which embodies a bold principle: using the affected limb more often leads to better functional recovery. By restricting the unaffected limb, CIMT compels the patient to engage the weaker arm, thereby challenging the nervous system to rewire itself toward more purposeful, coordinated use. This approach is not a one-size-fits-all prescription; therapists carefully select candidates based on the patient’s endurance, safety, and motivation. When implemented judiciously, CIMT can accelerate gains in dexterity and functional use of the affected hand, promoting a shift from compensation to genuine recovery. While CIMT often exists alongside other modalities, its core message aligns with the broader OT aim: meaningful repetition in realistic contexts yields durable improvements that translate directly into daily life.

Therapy also embraces activity-based training that centers on common, everyday actions rather than abstract movements. By retraining movement patterns within familiar settings, OT practitioners help patients reassemble the building blocks of independence. This means practice that mirrors dressing routines, meal preparation, and personal care, all tailored to the individual’s unique goals and living situation. The emphasis on goal orientation matters. When a patient values cooking for family or returning to a preferred hobby, therapy becomes a co-creative process where success is measured by relevance and achievement in daily life. The brain’s plasticity thrives on tasks that matter to the person and that are approached with clear, attainable steps.

Cognitive rehabilitation also plays a critical role within OT’s framework for stroke recovery. Impairments in attention, memory, and problem-solving can hamper day-to-day functioning long after motor symptoms begin to improve. OT integrates cognitive strategies with motor practice, teaching patients how to plan, sequence, and monitor their performance during tasks. For example, a patient may learn to chunk a dressing routine into smaller steps, use cues to maintain focus during a meal, or adopt problem-solving routines to manage a disrupted morning ritual. This cognitive-motor integration helps ensure that gains in movement translate into trustworthy independence rather than fragmented or inconsistent performance. It also supports safer engagement in home and community activities, which in turn nurtures confidence and reduces the fear of failure that often follows a stroke.

Beyond the clinic, occupational therapists extend their reach into the home and community, recognizing that recovery continues in the spaces where life unfolds. A home safety assessment becomes a foundation for sustainable progress. Therapists identify potential hazards, adjust layouts, and introduce adaptive strategies that maintain safety while preserving autonomy. Simple environmental modifications—such as reorganizing commonly used objects within easy reach, improving lighting, or rearranging a workspace—can dramatically reduce fatigue and frustration. Assistive devices, too, are considered through a critical lens of usability and relevance. From dressing aids to utensils with improved grasp or reachers that make retrieval tasks easier, devices are chosen not for their novelty but for their capacity to restore practical independence. Fatigue management and energy conservation are woven into this planning, teaching patients to pace activities, take strategic breaks, and distribute challenging tasks across the day so that endurance supports rather than undermines achievement.

The holistic approach of OT also integrates education for patients and caregivers. Understanding the why behind exercises, the how of safe movement, and the when of rest empowers families to participate meaningfully in recovery. Goal setting becomes a collaborative, ongoing conversation that honors the patient’s values, roles, and routines. Therapists help patients reconnect with meaningful roles—whether as a parent, a worker, a volunteer, or a neighbor—and frame recovery as a pathway back to those identities. This emphasis on psychological well-being and social reintegration is as essential as physical restoration. Confidence, self-efficacy, and a sense of belonging in home and community environments all depend on achieving progress in tasks that matter most to the person.

In practice, the journey of stroke recovery through OT is iterative and personalized. Therapists continually reassess capabilities, adjust activities, and refine strategies to maintain momentum. The path forward is rarely linear; rather, it unfolds as a dialogue between what the patient can do today and what their goals demand tomorrow. The patient’s environment, support network, and lived experience shape the pace and shape of therapy. When caregivers are engaged as partners in care, the patient’s practice extends beyond therapy sessions, sustaining improvements and reinforcing new habits. Acknowledging the emotional weight of the recovery process, therapists also offer empathy and practical guidance that help survivors rebuild their sense of self—moving from vulnerability to competence, from dependence to contribution, and from isolation to participation in everyday life.

Ultimately, the objective is not merely to restore movement but to restore the sense that life remains rich with possibility. OT helps patients reimagine daily routines by aligning movement with purpose. It offers a bridge from the clinic to the kitchen, the bedroom, the bank, and the playground of the community. As upper-limb function improves, so does the ability to manage personal care and domestic tasks, return to work or volunteering, and engage with friends and family without the constant fear of failure. The chapter of stroke recovery that OT authorizes is written in small, attainable successes—each one a stepping stone toward renewed independence, dignity, and social participation.

For readers seeking additional practical examples that illustrate these principles in action, exploring stroke-focused OT exercises can provide a concrete sense of how task-based practice translates into daily gains. See the resource linked earlier for a diverse set of activities that target hand function and coordination in everyday contexts.

For a broader, evidence-based synthesis of OT’s role after stroke, consider the following external reference: Role of occupational therapy after stroke.

Harnessing Evidence-Based Occupational Therapy Techniques to Restore Independence After Stroke

Occupational therapy (OT) stands as a cornerstone of stroke rehabilitation, dedicated to restoring a person’s ability to engage in meaningful activities and regain functional independence. The aftermath of a stroke often leaves individuals grappling with impairments in motor skills, coordination, and cognitive abilities, which collectively undermine one’s capacity to perform daily activities such as dressing, cooking, or bathing. The targeted approach of occupational therapy addresses these challenges through interventions grounded in rigorous scientific evidence, ensuring therapies not only improve physical outcomes but also bolster cognitive and emotional resilience.

One of the fundamental strategies in occupational therapy for stroke recovery is task-oriented training, which focuses on practicing the very activities that patients wish to resume in their daily lives. By repetitively engaging in goal-directed tasks—be it buttoning a shirt, preparing a simple meal, or grooming—patients stimulate the brain’s neuroplastic capabilities. This repetitive, purposeful practice fosters the reorganization of neural pathways, leading to improved motor function and greater ease in performing everyday tasks. Unlike abstract exercises, task-oriented training ensures that rehabilitation is meaningful and directly relevant to each individual’s unique lifestyle and priorities.

A particularly impactful intervention within this context is Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT). This technique counters the common post-stroke phenomenon where the unaffected limb dominates, resulting in neglect or disuse of the affected side. By restraining the less impaired limb for extended periods, CIMT compels patients to use their impaired arm, actively encouraging motor recovery. This forced use harnesses the brain’s adaptability, promoting the strengthening of neural circuits controlling the affected limb and gradually restoring its functional capacity. The success of CIMT has been validated by numerous clinical studies demonstrating gains in upper-limb mobility and daily function.

Apart from direct motor rehabilitation, occupational therapy plays a vital role in adapting the patient’s environment to support independence and safety. Stroke-related impairments can make everyday homes and workplaces hazardous or difficult to navigate. Therapists conduct thorough assessments of living spaces to identify potential barriers and recommend modifications or assistive devices. These may include installing grab bars in bathrooms to reduce fall risk, introducing specialized dressing aids to support independence in clothing tasks, or rearranging kitchen layouts to facilitate safer cooking and food preparation. Such environmental adaptations minimize reliance on caregivers and empower stroke survivors to confidently manage their surroundings.

Cognitive deficits are often overlooked but critically impact a stroke survivor’s ability to function independently. Attention, memory, problem-solving, and executive functions are frequently compromised, making it difficult to plan and complete daily activities. Occupational therapists incorporate cognitive rehabilitation techniques to improve these mental capabilities alongside physical recovery. Through structured activities designed to enhance focus, memory sequencing, and decision-making, patients learn to compensate for deficits and regain control over complex tasks. Cognitive training might involve practical exercises such as managing medication schedules, organizing daily routines, or problem-solving scenarios that mimic real-life challenges.

The integration of physical and cognitive rehabilitation within occupational therapy acknowledges that regaining independence is multifaceted. Enhancing motor skills without addressing cognitive challenges limits the effectiveness of recovery. Conversely, addressing cognitive function helps stroke survivors not only perform activities but also adapt to their new circumstances with greater confidence. This holistic approach promotes psychological well-being, reduces frustration, and facilitates smoother reintegration into social roles at home, work, and within the community.

To augment these therapeutic techniques, occupational therapists often educate patients and caregivers about energy conservation and fatigue management. Post-stroke fatigue is a common barrier to sustained rehabilitation progress. Learning to pace activities, prioritize tasks, and implement rest strategies can make therapy more manageable and improve overall quality of life. Educating families ensures that the support system around the stroke survivor understands these nuances, contributing to a collaborative recovery environment.

The role of assistive technology and adaptive equipment in OT cannot be overstated. Tools like specialized cutlery, reachers, or chair lifts, tailor-made for the individual’s condition, enhance the ability to perform tasks that might otherwise be impossible post-stroke. Engagement with technology and adaptive devices is carefully coordinated by therapists to complement therapeutic goals and maximize independence.

It is crucial that these interventions remain patient-centered, evolving with ongoing assessment and feedback. Personalized therapy plans ensure that treatment progresses in alignment with recovery milestones and patient preferences. This approach fosters motivation and engagement—two essential components for successful rehabilitation outcomes.

For those interested in delving deeper into comprehensive, research-backed practices on occupational therapy’s role in stroke management, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides detailed guidelines. These evidence-based recommendations further articulate the importance of multi-dimensional rehabilitation approaches that include occupational therapy as an integral component: NICE Stroke Guidelines.

In sum, occupational therapy utilizes a spectrum of evidence-based interventions—from task-oriented training and constraint-induced movement therapy to environmental adaptations and cognitive rehabilitation—to holistically support stroke survivors in reclaiming independence. This tailored, research-driven approach not only targets physical and cognitive impairments but also nurtures emotional well-being and social reintegration, laying a foundation for a meaningful and autonomous post-stroke life.

For readers seeking additional insight into specific therapeutic strategies and tools used by occupational therapists, exploring tools and equipment for occupational therapists offers valuable context on how these resources complement intervention plans and enhance recovery.

Transforming Spaces for Recovery: How Environmental Modifications Enhance Stroke Rehabilitation Through Occupational Therapy

A crucial yet sometimes overlooked facet of stroke recovery lies beyond direct physical rehabilitation exercises: the environment in which a survivor lives and functions. Occupational therapy recognizes this by focusing not only on restoring individual motor and cognitive abilities but also on reshaping the surroundings to support and amplify those gains. Environmental modifications are therefore integral to helping stroke survivors regain independence, reduce risk, and engage meaningfully with daily life.

After a stroke, individuals often face significant physical and cognitive challenges that impair their ability to perform basic tasks such as bathing, dressing, cooking, or moving safely around their home. These difficulties are not purely medical; they are compounded by obstacles present in the environment itself. Bathrooms with slippery surfaces, narrow doorways, or furniture arranged without consideration for reduced mobility can create barriers that threaten safety and limit autonomy. Occupational therapists assess a patient’s interaction with their living spaces to identify such barriers and craft solutions tailored to each person’s unique needs and abilities.

The goals of environmental modifications revolve around promoting functional independence and preventing secondary complications. Practical changes are implemented with a clear focus on enhancing safety and usability of the survivor’s surroundings. For example, installing grab bars in bathrooms provides stable support during transfers in and out of the tub or shower, significantly reducing fall risks. Removing loose rugs and cluttered objects eliminates tripping hazards. Adding non-slip mats and improving lighting further ensure safe navigation through often challenging areas. Adjusting furniture heights can accommodate limitations in balance, reach, or strength, enabling a survivor to sit, stand, and transfer with greater ease. These modifications empower stroke survivors to carry out essential activities with less assistance, thus restoring confidence and fostering a sense of control over their environment.

Timing plays a vital role in the effectiveness of these interventions. Environmental modifications are often most impactful when implemented during the recovery phase, roughly three to six months after the stroke event. At this stage, patients are typically most engaged in intensive rehabilitation and more responsive to integrating adaptive strategies that complement motor and cognitive therapies. However, the need for modifications persists beyond this period as stroke survivors transition toward long-term living with residual impairments. In this post-acute phase, occupational therapists shift focus to sustaining independence through training in assistive device use and refining routines that accommodate ongoing challenges.

Beyond physical adaptations, the concept of environmental enrichment has emerged as a powerful driver of neurological recovery. Enriched environments—those rich in sensory, cognitive, and social stimuli—have been shown to catalyze neuroplasticity, the brain’s remarkable capacity to reorganize after injury. This reorganization underpins improvements in motor function, attention, and problem-solving skills essential for everyday activity. By creating living spaces that stimulate engagement and provide opportunities for meaningful interaction, occupational therapy supports not only physical but also cognitive rehabilitation.

Occupational therapists play a central role in guiding stroke survivors and their families through this comprehensive approach to environmental adaptation. They conduct detailed assessments that consider physical layout, accessibility, safety risks, and personal routines. These assessments inform personalized modification plans that align functional goals with available resources and patient preferences. Education is a key component: therapists teach safe techniques for mobility and transfers, instruct on the proper use of adaptive devices, and advise on energy conservation to manage fatigue common after stroke.

An important aspect of environmental modification is its collaborative nature. Occupational therapists often coordinate with caregivers, family members, and other healthcare professionals to ensure that changes in the home or workplace are both practical and sustainable. This team approach enhances implementation success and provides emotional support critical to long-term adjustment. Furthermore, modifications extend beyond the home environment; workplaces and community settings are also evaluated to facilitate the reintegration of stroke survivors into meaningful roles.

Technological advancements and creative solutions have expanded the realm of possibilities for environmental adaptation. Examples include adjustable beds and chairs, smart lighting systems for improved visibility, and customized tools that accommodate limited hand function. These innovations, combined with traditional strategies, create a supportive framework that addresses the spectrum of challenges stroke survivors face. By harnessing both simple and sophisticated tools, occupational therapy continuously evolves to meet patient needs dynamically.

In sum, the integration of environmental modifications within occupational therapy represents a holistic method that accentuates stroke rehabilitation outcomes. Altering physical surroundings to reduce barriers not only makes daily tasks safer but also stimulates neural recovery mechanisms and nurtures psychological well-being. As survivors regain autonomy in familiar settings, they rebuild confidence and rediscover their identity beyond the stroke. These transformations in environment and ability together unlock a path toward renewed independence and quality of life.

For readers interested in learning more about the practical aspects of adapting living spaces to patient needs, the blog post How Do Occupational Therapists Assist in Adapting Environments for Patient Needs? offers valuable insights into this collaborative process.

More detailed guidelines and evidence-based recommendations on environmental modifications in stroke recovery are available through the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA): Stroke Recovery and Environmental Modifications.

Rewiring Lives: How Occupational Therapy Rebuilds Cognition, Skills, and Independence After Stroke

Even when the stroke has left the body weaker in some places and sharper in others, the daily rhythm of life remains the true measure of recovery. Occupational therapy emerges as a bridge between the mind’s aspirations and the body’s capabilities, guiding patients through tasks that matter to them. After a stroke, many survivors face not only motor and sensory changes but also shifts in attention, planning, problem solving, and memory. OT recognizes that regaining independence is a holistic process. It asks not only how to move a hand again, but how to plan a morning routine, how to choose clothes that fit a changed body, and how to engage with others in meaningful activity. In this light, recovery becomes less a race to restore a pre-stroke map and more a process of constructing a workable life within new limits, with dignity intact.

At the core of cognitive recovery is the deliberate reactivation of brain networks through practice that is purposeful and repetitive, yet highly meaningful. OT’s cognitive rehabilitation approach treats attention, memory, problem solving, and executive function not as separate silos but as intertwined capacities that enable daily performance. Therapists design tasks that demand planning, inhibition of distractions, and flexible thinking while also requiring motor control. The brain learns by doing, and repetition in authentic contexts strengthens the circuits needed to manage real life. The goal is to shift from generic cognitive drills to activities that resemble the person’s real responsibilities, such as managing medications, following a recipe, or coordinating a schedule. This shift makes cognitive gains transferable to daily life, which in turn bolsters confidence and participation in social roles.

One established framework that captures this integration is Functional and Cognitive Occupational Therapy, or FaCoT, which fuses cognitive training with functional task practice inside meaningful life situations. The essence is to pair mental tasks with hands-on activities so patients relearn not only what to do but how to do it efficiently under fatigue, pain, or uncertainty. In practice, therapists guide patients through tasks that resemble daily routines, such as preparing a simple meal, budgeting a small amount, or organizing a closet. The integration helps patients recognize when memory lapses or attention slips occur and develop compensatory strategies before those problems derail performance. For examples of stroke-related cognitive exercises aligned with this approach, see occupational therapy exercises for stroke. This linkage between mind and action supports not just accuracy but the speed and smoothness of task completion, which matter greatly to independence over time.

Beyond cognition, FaCoT and conventional OT share a common goal: turning cognitive insight into durable functional gains. Therapists assess what a person can do now and what remains out of reach in daily life, then tailor interventions to close that gap. Functional assessments look at activities of daily living—dressing, bathing, feeding, grooming, and transfers between sit-to-stand and mobility tasks. Evaluations also include perceptual skills, spatial awareness, and the ability to sequence steps, since a misstep in any of these areas can derail a simple activity. As the patient progresses, the therapist introduces adaptive strategies that preserve energy and reduce fatigue. These strategies might include pacing tasks, using visual cues, or reorganizing a kitchen so frequently used items are within easy reach. In addition, home safety becomes a central concern, with therapists teaching fall-prevention techniques and guiding caregivers in supporting gradual independence rather than enabling dependency.

Movement rehabilitation is not left behind in these cognitive-centered plans. Occupational therapy embraces evidence-based motor approaches alongside cognitive tasks, and one well-known method is constraint-induced movement therapy, or CIMT, which prompts use of the affected limb by limiting the non-affected one. Although CIMT requires careful selection of candidates, when feasible it can drive meaningful gains in dexterity and coordination by overtly reversing learned disuse. OT practitioners weave CIMT into broader activity-based training, so practice focuses on real-life activities rather than isolated motions. For example, a therapist may guide a patient to button a shirt, tie a knot, or grip a cup while the unaffected arm remains restrained. The rationale is simple: repeated, goal-directed use of the affected limb promotes neuroplastic changes that translate into improved functional use. When CIMT is coupled with functional task practice, patients not only relearn movement patterns but also integrate them into routines that support independence at home and in the community.

Task practice in FaCoT is rarely abstract. Therapists use simulated real-life tasks that resemble the patient’s daily responsibilities, and the realism helps transfer gains to everyday life. Repetition is balanced with feedback, enabling patients to notice errors, adjust strategies, and monitor their own progress. This metacognitive loop—the awareness of one’s own thinking during problem solving—often strengthens self-management skills, a critical factor in long-term recovery. The approach recognizes that cognitive challenges such as slowed processing or distractibility can make even simple errands daunting. By embedding cognitive demands in meaningful activities, therapists give people a sense of mastery rather than frustration, which is essential for sustained participation in family life, volunteering, or return to work. The social dimension matters too, because engaging with others during these tasks supports mood, motivation, and accountability.

An OT plan also extends into the home environment, where safety and accessibility shape how much recovery can translate into daily life. Home assessments identify hazards, arrange furniture in ergonomically friendly layouts, and propose adaptive equipment that fosters independence. Simple aids—such as devices that extend reach, or utensils designed for easier grip—can reduce effort and minimize fatigue during meals or personal care. Importantly, occupational therapists educate patients and caregivers about energy conservation and fatigue management. They help families schedule activities during peak alertness, plan rest breaks, and alternate demanding tasks with easier ones. This approach does more than preserve function; it preserves identity. When people feel capable in familiar spaces, they are more likely to reengage with friends, maintain routines, and pursue meaningful activities like hobbies, volunteering, or caring for loved ones.

Emotional well-being and social participation are inseparable from physical recovery. Depression and fatigue commonly accompany stroke and can undermine motivation and adherence to therapy. An integrated OT strategy acknowledges these emotional factors and supports resilience through meaningful tasks, social engagement, and small victories. Group sessions, peer support, and problem-solving discussions give survivors a sense of companionship and shared purpose. The work of OT becomes not merely about acquiring skills but about rebuilding confidence in the face of vulnerability. When the person can contribute to family life, manage a modest kitchen routine, or handle personal care without constant assistance, the social world expands rather than narrows. In many cases, these changes ripple outward, enhancing relationships with caregivers and reducing caregiver strain, which in turn reinforces the patient’s sense of value and belonging.

Bringing these cognitive and functional dimensions together requires a coordinated, person-centered approach. Occupational therapists work within interdisciplinary teams to align goals with medical status, home resources, and the patient’s personal priorities. They translate clinical findings into practical plans, help bridge hospital discharge to home, and pace the tempo of recovery to match fatigue levels and medical stability. Education for families and caregivers is a cornerstone, ensuring continuity of practice, consistency in expectations, and a shared language for progress. The ultimate aim is not to return to a pre-stroke baseline alone but to sculpt a sustainable life in which the person can pursue roles once thought unattainable, whether at home, at work in modified capacities, or in community life. This perspective frames OT as a living therapy, adaptable to changing needs, rather than a fixed set of exercises.

Viewed through this lens, occupational therapy becomes a dynamic partnership—one that honors the person’s goals, negotiates the realities of fatigue, and harnesses the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself in service of independence. For a deeper exploration of the FaCoT model and its evidence base, see the external resource: https://www.mdpi.com/1423-0380/23/6/2758.

Restoring Identity After Stroke: Occupational Therapy’s Role in Psychological Recovery and Social Reintegration

Occupational therapy (OT) does far more than rebuild muscle strength and fine motor control; it helps stroke survivors reconstruct a sense of self and reconnect with the life they value. When routines, independence, and familiar roles are disrupted by a stroke, people often face problems that are emotional and social as much as they are physical. Occupational therapists target those invisible but crucial losses—confidence, purpose, and participation—by designing personalized, meaningful interventions that restore daily competence and encourage community engagement.

A central principle of OT in stroke recovery is meaningful occupation: using activities that matter to the person as the primary vehicle for rehabilitation. Rather than isolated repetition of movements, therapists embed practice in tasks that reflect a patient’s roles and interests. Preparing a simple breakfast, handling a bank card, gardening, or returning to a hobby are chosen not only to exercise impaired muscles or attention but to produce real-world success. These successes are powerful. Completing a familiar task affirms capability, reduces helplessness, and rebuilds self-esteem. Over time, repeated mastery of meaningful tasks counters feelings of apathy and low motivation, common emotional sequelae after stroke.

Occupational therapists set collaborative, goal-oriented plans. Goals are functional and personally relevant—dressing independently for an older adult, managing medication for someone with chronic conditions, or using public transport to meet friends. This goal-directed approach gives therapy a clear purpose and a path for measurable progress. Clients are involved in selecting goals, which fosters ownership and autonomy. Small, scaffolded wins are celebrated and used to motivate further effort. Therapists teach strategies to break complex tasks into manageable steps, use visual or verbal cues, and apply compensatory techniques when full recovery of a function is unlikely. These tools maintain dignity and reduce anxiety by offering practical routes to independence.

Cognitive and emotional challenges are often intertwined after a stroke. Problems with attention, memory, executive functioning, and problem-solving can limit the ability to return to everyday roles. Occupational therapists integrate cognitive rehabilitation with everyday activities. For example, a therapy session might mimic preparing a meal while also training prospective memory by using checklists and timers. This dual focus trains cognitive skills in context, improving transfer from clinic to home. Emotional support is woven into the process: therapists validate grief and frustration, normalize setbacks, and coach clients in managing stress and fatigue. Techniques such as graded activity, energy conservation education, and paced task practice reduce overwhelm and prevent relapse into inactivity, which can compound depression and social withdrawal.

Social reintegration is a clear OT priority. After a stroke, many people withdraw from social roles because they fear embarrassment, struggle with mobility, or lack confidence in managing outings. Occupational therapists use graded exposure and simulated real-life scenarios to rebuild social participation. In structured sessions, therapists rehearse activities like grocery shopping, crossing a street, or navigating a café. They train practical skills—managing money, operating a phone, or using public transit—and teach communication strategies for those with language or cognitive impairments. These rehearsals reduce fear of failure and equip individuals with routines to fall back on when they return to the community.

Community-based programs and home visits are essential OT methods for promoting social engagement. Therapists assess the actual environments where life happens: kitchens, bathrooms, workplaces, and neighborhoods. They identify barriers and propose realistic modifications—rearranging furniture for safer mobility, recommending adaptive cutlery, or advising on bathroom grab-bars and shower chairs. These changes are often low-cost but high-impact. Making a living space more accessible encourages independence and invites social interaction by reducing reliance on caregivers. Occupational therapists also work with caregivers and family members, teaching them supportive strategies that encourage participation rather than foster dependence. This family-centered education balances safety with autonomy and reduces caregiver strain by clarifying realistic expectations.

Return to work and vocational roles is another area where OT bridges physical and psychosocial recovery. Therapists evaluate job demands and create graded return-to-work plans, often coordinating with employers to modify tasks or schedules. Vocational rehabilitation might include workplace simulations, assistive technology recommendations, or phased re-entry. Securing a meaningful role at work—or finding an alternative that fits post-stroke abilities—provides financial stability and restores identity, contributing substantially to psychological well-being.

Occupational therapy also addresses stigma and social identity. Stroke can change how individuals see themselves and how others perceive them. Therapists help clients develop narratives that integrate impairment into life stories without allowing it to define them entirely. Group OT sessions and community programs create peer support opportunities. Sharing experiences with others facing similar challenges reduces isolation, normalizes struggles, and fosters practical problem-solving. Group activities can also serve as social skills practice, offering a safe space to try new behaviors and rebuild confidence.

Technology and adaptive equipment widen possibilities for participation. From simple devices like reachers and dressing aids to communication software and mobile reminder apps, OT specialists match tools to goals. Training in assistive devices is always embedded in meaningful tasks, ensuring the technology actually improves daily life. On the social side, learning to use a smartphone for video calls or social media can reconnect people with distant friends and family, supporting emotional recovery.

Measuring psychological and social outcomes matters. Research shows that OT interventions that focus on meaningful activity and participation improve self-care abilities and social involvement. Evidence links these improvements to better mental health outcomes—reduced depression, enhanced self-efficacy, and increased life satisfaction. Therapists use standardized assessments and client-reported outcomes to track progress in areas such as social participation, mood, and role performance. These measures guide ongoing therapy and demonstrate the holistic impact of OT beyond physical metrics.

Ultimately, occupational therapy’s contribution to stroke recovery lies in its holistic, person-centered approach. It treats the whole person—mind, body, and social context—rather than isolated deficits. By reconnecting people with meaningful activity, rebuilding practical skills, adapting environments, and facilitating social reentry, OT restores capability and identity. This restoration reduces emotional distress and opens pathways back to valued roles in family, work, and community.

For further reading on evidence supporting these outcomes, see the systematic review in the Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation: https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-025-02317-9

For more about how occupational therapy supports emotional and mental health during rehabilitation, explore this resource on how occupational therapy supports mental health: https://coffee-beans.coffee/blog/how-occupational-therapy-supports-mental-health/

Final thoughts

Occupational therapy proves to be an invaluable asset in the journey of stroke recovery, encapsulating a holistic approach that caters to physical rehabilitation, cognitive enhancement, and mental well-being. By focusing on improving motor skills, addressing cognitive deficits, modifying environments, and fostering social connections, occupational therapists empower stroke survivors not just to regain their independence but to thrive in their daily lives. In recognizing the seamless interplay of these components, we see how OT serves as a cornerstone in the recovery process, enabling individuals to reclaim not only their routines but their confidence and sense of purpose. As we move forward, the significance of occupational therapy in stroke rehabilitation cannot be overstated; it is essential for business owners and communities alike to advocate for these services that fundamentally transform lives.