Coffee is at the heart of many businesses, from cafés to catering services. As a business owner, understanding the lifespan of your coffee beans is crucial not only for maintaining the quality of your products but also for ensuring customer satisfaction. Coffee beans don’t have a traditional expiration date like perishable goods; instead, they have a ‘best-by’ date that primarily refers to flavor and freshness. In the following chapters, we will explore the nuances of coffee bean expiration, the factors leading to flavor degradation, the safety of consuming expired coffee beans, and effective storage methods to maximize freshness. This comprehensive overview will empower you and your business to navigate the world of coffee beans with confidence.

Do Coffee Beans Expire? Decoding Best-By Dates, Flavor Windows, and Safe Storage

Do coffee beans really expire, and should a printed date govern what you pour into your cup tomorrow or next week? The short, practical truth is that expiration on coffee beans is primarily about flavor, not safety. Roasted beans are hardier than their aroma would have you believe, and their most important clock is the one that governs freshness of taste and scent, not a health hazard. When we unpack what the labels mean and how storage conditions shape what reaches your palate, a more nuanced picture emerges. It helps to think of coffee as a living bouquet rather than a perishable commodity that must be discarded at the first hint of age. The goal is to keep flavor intact for as long as possible, or to adapt your brewing approach if the beans have aged beyond their peak. In that sense, the question, “Do coffee beans expire?” becomes a question about flavor trajectory, aroma, and the practical moments when a bean’s character begins to slip rather than about danger in the cup.

The most common guidance to anchor our understanding starts with a straightforward frame: roasted coffee beans typically carry a shelf life of roughly 12 to 18 months under proper storage. That range is a practical guideline for the period during which the beans will retain their best aroma, acidity, and the complex tapestry of flavors that characterizes a fresh roast. Within that broad window, the clock also depends on how soon after roasting the beans were packaged and how they have been stored since. In many cases, the printed “best-by” or “use-by” date reflects a manufacturer’s estimate of peak flavor quality rather than a safety cutoff. It is common to see peak flavor within a narrow window—often the first one to three months after roasting—though under ideal, sealed, cool, dark storage, that peak can extend to four or six months. The literature and industry practice acknowledge this nuance: the date helps retailers and home cooks anticipate flavor quality, not safety.

To understand what changes as time wears on a batch of beans, it helps to imagine the journey of flavor compounds. Coffee’s aroma is a delicate orchestra of volatile compounds: esters, aldehydes, ketones, and various acids all play their parts. When beans are roasted, these compounds are locked in and then slowly exposed to air and light, beginning a gradual dance of oxidation. The longer coffee sits, the more those lively notes—bright fruit, jasmine, cocoa, stone fruit, or toasted nuts—fade. The acidity that gives coffee its sparkle often drops away, leaving a cup that can taste flatter or, in less favorable circumstances, bitter or hollow. Caffeine, the familiar pick-me-up, remains relatively stable through storage, which means the shifting flavor and aroma are what primarily drive the perception of freshness and energy in a cup.

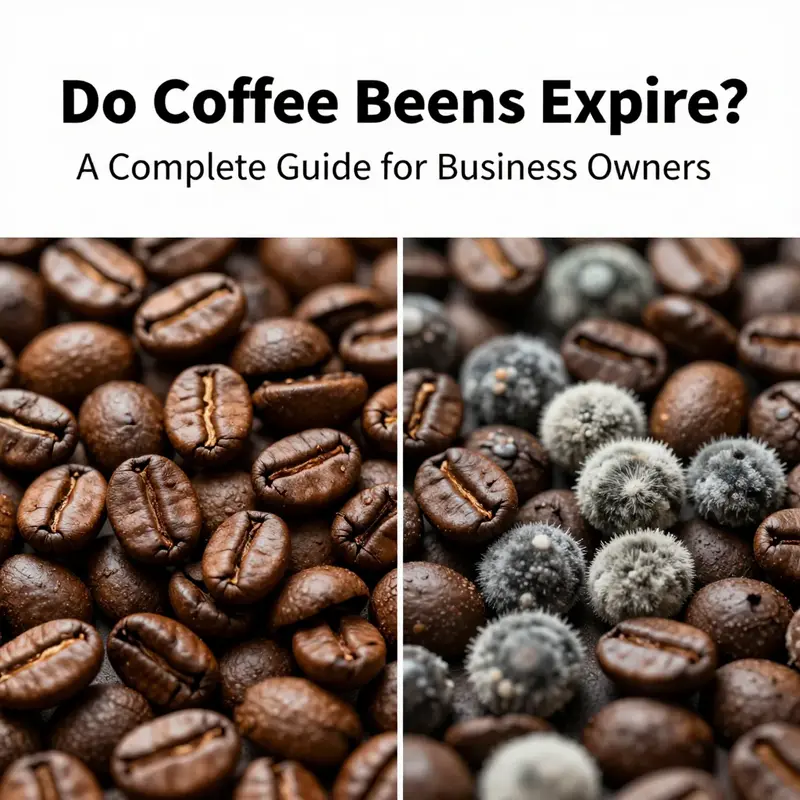

Storage conditions are the hinge on which flavor hinges. A dry, airtight environment in a cool, dark place slows oxidation and helps preserve aromatic compounds longer. When beans are stored in a sealed container with little exposure to air, light, and heat, they can keep their best qualities for a longer portion of the 12–18 month window. Conversely, moisture, heat, or direct light accelerates flavor loss and risks spoilage. While dry beans are naturally resistant to mold and bacterial growth due to their low moisture content, bad storage can invite other risks. The most common, practical signs of trouble are sensory: a dull, stale aroma; a muted or sour flavor; and, in extreme cases, off smells like mustiness, rancidity, or sourness that suggests oxidative or fat rancidity. If mold were to appear—white, green, or black patches on the surface—or if a strong, pungent, rancid odor emerges, these are clear signals to discard the beans. In short, the printed date is not a safety line in the sand; it’s a compass pointing toward peak flavor, with clear cues for when something has gone astray.

Ground coffee versus whole beans introduces another layer to the equation. Ground coffee loses its aroma and flavor more rapidly because grinding increases the surface area exposed to air. The protective advantages of whole beans—whole beans retain their volatile compounds longer because the interior remains insulated from oxygen—are real. This means a bag of whole beans can ride the clock a bit longer in terms of peak flavor if stored correctly, whereas ground coffee begins to fade quickly once opened. Even so, both forms can be safe to drink well past the printed date if they show no signs of spoilage and if your expectations shift accordingly. The difference lies in flavor potential and how forgiving your brewing approach is likely to be.

In practice, the literature suggests a pragmatic approach to consumption past the best-by date. If beans are only modestly past their date—say, one to two months—and have been well sealed and stored properly, they are generally safe to drink. Check for mold, discoloration, and strong rancid or musty smells. If any of these signs are present, discard. If the beans appear dry, dry and crisp rather than moist or clumped, they are more likely to yield a usable cup with modestly reduced flavor. When flavor is the priority, consider adapting your brew to coax out what remains. A higher brew temperature within the safe range, a slightly coarser grind, and a longer extraction can help you draw more flavor from older beans. Milk-based drinks can also soften the perception of diminished complexity, thanks to the mouthfeel and sweetness of dairy that can mask some flavor weaknesses.

However, as time extends beyond a few months past the date or if storage has been less ideal, the calculus shifts. If a batch is more than three months past its expiration date, particularly with imperfect storage conditions, many coffee lovers decide to avoid brewing with it altogether. The risk is not a health hazard in the sense of foodborne illness in typical dry-roasted beans, but there is a real possibility of a flat, off, or even rancid flavor that makes the experience unpleasant or unrecognizable from the original profile. In such cases, pouring the beans down the drain is a kinder fate than serving coffee that might be difficult to enjoy and could cause digestive upset for some individuals who are sensitive to rancid fats or mycotoxins in microenvironments. The preference, then, is to rotate stock, buy what you can use within a reasonable time frame, and minimize the number of opened bags resting on the counter or shelf.

This perspective aligns with a broader truth about food and drink in general: if storage remains dry, cool, and dark, and if the beans show no visible signs of spoilage or odor anomalies, you are likely safe from a health standpoint. The safety argument rests on moisture control and microbial growth. Dry beans are not hospitable to mold or bacteria in the same way perishable foods are, and the roasting process reduces moisture to levels that further inhibit microbial life. The danger, when it exists, is primarily the quality degradation that comes with time rather than a safety hazard. That said, there are exceptions. If beans have been exposed to warmth, humidity, or contaminated packaging, or if they show mold growth, signs of pests, or unusual odors that resemble solvents or rotten plant matter, discard immediately. The bottom line for safety and taste is to rely on your senses. Look, sniff, and taste in small quantities. A mild roast aroma that fades to a neutral or slightly sweet scent is often an acceptable sign that the beans are past their prime but still usable in a pinch. A strong rancid, sour, or musty odor is a strong signal to discard.

The practical implications for brewing are telling. If you choose to use older beans, you may notice reduced acidity, a flatter mouthfeel, and diminished aromatic complexity. The acids that keep coffee bright, such as chlorogenic acids and their derivatives, degrade over time, flattening what once might have been a bright, lively cup. The drink may lean toward a dull or bitter profile, even if the cup is clean and free of off smells. To maximize enjoyment, many home brewers adapt by selecting brewing parameters that intensify extraction of the remaining flavor notes. This might mean experimenting with a hotter water temperature within safe limits, a slightly finer grind to increase surface area, or a longer brew time to compensate for diminished solubility. Each adjustment should be guided by sensory feedback—if the brew tastes like flat water or exhibits an overpowering burnt or ashy edge, it’s a signal to recalibrate or to retire the beans.

A more nuanced consideration is the distinction between packaging and storage patterns. The bag in which coffee is sold is designed to protect flavor, often featuring one-way valves that let CO2 escape while blocking oxygen from entering. This helps preserve freshness for longer if the bag remains sealed between uses. Transferring beans to an airtight, opaque container further reduces exposure to light and oxygen. The container choice matters as much as the storage location. A cool pantry corner, away from heat sources and direct sunlight, is preferable to a sunny cabinet or a countertop near a stove. Temperature stability matters too. Fluctuations—such as moving beans from a warm kitchen to a refrigerator and back—can cause condensation when the container is opened, leading to moisture intrusion that accelerates flavor degradation and potentially invites spoilage processes. If you choose to refrigerate or freeze beans for long-term storage, it should be done with caution and discipline. The beans should be placed in airtight, moisture-proof packaging, and you must allow them to return to room temperature in the sealed container before grinding. Ground coffee, with its greater surface area, does not tolerate repeated cycles of cooling and warming as well as whole beans, so freezing and thawing is generally more suitable for whole beans intended to be ground just before brewing.

In light of these dynamics, many coffee enthusiasts adopt a practical stock-management approach. Buy in smaller quantities, especially if you drink infrequently or are chasing a specific flavor profile. Prioritize a rotation system where the oldest beans are used first, ensuring you always have a fresh supply without letting bags linger past their prime. If a bag has been opened, transfer the beans to an opaque, airtight canister and keep it away from light and heat. If you have a larger stash, consider freezing the portions you are not currently using, ensuring they are sealed tightly to prevent moisture ingress. When thawing, avoid opening the frozen bag and exposing the entire contents at once. Instead, transfer a small handful to a separate container and use it within a few days. These practical steps can help align your coffee consumption with the natural flavor trajectory of roasted beans, delivering the best possible cup for as long as the beans remain pleasant to brew.

The discourse surrounding expiration also intersects with consumer expectations and the broader guidance from food-safety authorities. While the coffee community tends to emphasize flavor windows and the music of aromas, public health agencies frame shelf life in terms of safety and risk reduction. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, for instance, provides general resources on food safety and shelf life that can help consumers contextualize the idea of expiration dates across products. For readers who want to explore the official, value-neutral perspective on shelf life and safety, a reputable source such as the FDA’s consumer updates on food safety and shelf life offers a balanced framework for understanding how long products can be stored safely and what signs indicate deterioration. This broader lens reinforces the central message for coffee: your beans are not likely to harm you after their best-by date, but their flavor and aroma will decline, sometimes quite noticeably, as time passes and storage conditions falter.

Ultimately, the big-picture answer to the question—do coffee beans expire—is that they do not abruptly become dangerous after a printed date. Instead, they drift from peak flavor toward a flavor that’s less vibrant, and their aroma and acidity can become muted. The degree to which this matters depends on your palate, your goals for the brew, and how you store and handle the beans. If you cherish aromatic, nuanced cups, treat the best-by date as a compass for when to plan a swap to fresher beans. If you simply want a cup that is safe and drinkable, note the signs of deterioration and adjust expectations accordingly. The process is not about a binary safe-or-not threshold, but about managing a flavor-life cycle with practical care and sensory awareness.

In this light, the question moves from one of do coffee beans expire to one of how to steward flavor across time. A well-stored bag of whole beans retains its character longer than the same beans ground and left exposed to air. A gentle rotation of stock, mindful storage, and a willingness to adapt brewing methods as beans age—all these strategies help you extract the most from your coffee over the course of its flavor life. The printed date remains a useful guide, a kind of flavor weather report, but it does not obligate you to discard the beans the moment that date creeps past. Instead, use your senses, respect the signs, and enjoy the journey of coffee—from the moment of roasting to the moment it touches your lips. If a batch carries a faint, complex perfume of roast and fruit, savor it; if it arrives flat, drink it anyway with curiosity, perhaps in a milder brew that smooths the edges. Either way, the story of coffee beans is a story of flavor, time, and care rather than a simple countdown from cradle to grave.

For further context on shelf life and safe handling, you can explore authoritative guidance on food safety and shelf life provided by the FDA at https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/food-safety-and-shelf-life. This resource offers a broad framework to interpret shelf-life labels and to understand how storage conditions influence safety and quality across a wide range of foods and beverages, including roasted coffee beans. While the specifics of coffee flavor longevity are unique to aroma chemistry and brewing chemistry, the underlying principle remains consistent: storage matters, and sensory judgment matters even more when you’re deciding whether to grind and brew that bag today or save it for tomorrow.

In sum, the expiration date on coffee beans signals a window of peak flavor, not a danger period. It invites practical decisions about storage, rotation, and brewing technique to keep your cup characterful. When in doubt, trust your senses and lean on careful storage to preserve as much of that precious coffee coastline as possible. The goal is not to chase eternity in flavor but to enjoy the richest, most reliable cup within the time frame your storage ecosystem allows. And if a particular batch has already passed its personal peak, you still hold the option to repurpose it—perhaps as a base for cold brew or a bold espresso blend that benefits from a less delicate aromatic backbone—thereby honoring the beans’ journey rather than discarding them outright. The question of expiration, then, becomes a conversation about flavor, technique, and stewardship rather than a verdict on safety. It is a reminder that coffee is as much about how we treat it as it is about the beans themselves, and that thoughtful handling can extend the pleasure of a well-made cup even as time moves on.

null

null

Beyond the Best-By: Safety, Sensory Cues, and Realistic Timelines for Expired Coffee Beans

Every bag of roasted coffee beans carries a subtle clock. The printed best-by date is not a warning label for danger but a guide to flavor, aroma, and the bright, nuanced notes that coffee can offer at its peak. This chapter unpacks what expires in coffee beans, why, and how that expiration relates to safety. The distinction is important. A coffee bean can lose its luster long before it becomes unsafe to drink. Yet the way we store, perceive, and brew those beans can make the difference between a cup that tastes alive and a cup that tastes flat, stale, or disagreeable. When we talk about expiry in the context of coffee, we’re really discussing two intertwined ideas: the sensory lifespan—the period during which the aroma and flavor feel vibrant—and the longer-term question of safety, which is mostly about preventing mold and moisture-related spoilage. In practice, the two paths diverge, and understanding that divergence helps you decide what to do with older beans without overreacting to a labeled date.

The shelf life often cited in industry guidelines—roughly 12 to 18 months for roasted beans under proper storage—speaks to the peak flavor window. It is a signal that within that span, the beans are most likely to deliver their characteristic brightness, acidity, and complexity. Outside that window, flavor can fade, morph, or drift toward dullness or bitterness. Importantly, this window is about quality, not safety. Coffee beans are extraordinarily dry by the time they reach the consumer, a consequence of the roasting process that dramatically reduces moisture. Low moisture hinders microbial growth, which is why coffee can remain chemically stable long after its prime. If stored correctly, beans can stay safe to drink months or even years beyond the printed date. The risk that remains is not foodborne illness but the possible loss of the sensory qualities we seek in a bright cup.

To understand what happens as time passes, it helps to picture oxidation in a bag as a slow, relentless process. The volatile aromatic compounds that give coffee its signature perfume—fruity notes, floral brightness, chocolatey richness, nutty inflections—begin to break down. Within 30 to 60 days, many roasters and baristas would describe a detectable shift: aromas become muted, acidity softens, and the cup often tastes flatter or more one-dimensional. For many drinkers, that change marks a shift from “coffee at its best” to “coffee that’s still coffee.” The pace and degree of this shift depend on factors you can control—primarily how you store the beans. Exposure to light, heat, and moisture accelerates oxidation, while an airtight, opaque, cool environment slows it. Ground coffee, with its greater surface area, loses freshness more quickly than whole beans, so the relative urgency to use it up is even more acute.

Another layer to consider is the possibility of spoilage, though it remains relatively rare with dried coffee. When moisture seeps into a bag, or if beans are kept in a damp, warm closet or a poorly sealed container, mold can appear. Mold is not something to gamble with. The visible presence of white, green, or black spots on the surface, or a musty, sour, or rancid odor, are clear indicators that the product should be discarded. The moment you notice mold or any off-putting smell, you should not brew with those beans. In contrast, a clean, dry bag that smells like fresh coffee—even if the aroma is less vibrant than it once was—can safely be brewed, provided there are no other signs of deterioration. The safety line, then, rests on moisture control and perceptible spoilage signs rather than the date itself.

Health concerns, while a critical consideration for many, tend to be straightforward in this context. Coffee beans do not sprout dangerous pathogens in the same way as perishable foods such as meat or dairy. The roasting process already reduces moisture content to levels that are inhospitable to many bacteria. Consequently, the everyday risk of falling ill from drinking very old, properly stored coffee is minimal. Still, older coffee can cause mild digestive discomfort for some people. The fats and oils in roasted coffee can oxidize and produce compounds that irritate sensitive stomachs in certain individuals. In most cases, this is a matter of taste and tolerance rather than a health emergency. If you notice unusual stomach upset after drinking coffee from beans past their prime, it’s reasonable to stop and reassess your supply. This is especially true for people with sensitive digestive systems or for those who are particularly reactive to bitter or stale flavors.

What does proper storage actually entail? The practical answer is simple, but its impact is profound. Keep beans in a cool, dark place, away from heat sources and direct sunlight. A dedicated coffee canister with an airtight seal is ideal, provided it is kept in a cabinet or pantry rather than a sunny countertop. Avoid storing coffee in the fridge or freezer unless you intend to freeze for long periods and have a plan to prevent condensation. Freezing can preserve flavor, but it can also introduce moisture when you move beans back to room temperature unless you take care to seal them in moisture-proof packaging and only thaw what you plan to use. If you do freeze, portion the beans into small quantities so you only thaw what you need for a short period, minimizing repeated exposure to temperature changes. The essence of storage is to minimize oxygen exposure. Oxygen is the prime driver of oxidation, and oxidation saps aroma and flavor with each passing day.

Another practical dimension concerns the distinction between whole beans and ground coffee. Whole beans retain their structural integrity longer because the surface area with which oxygen interacts is smaller. Ground coffee exposes a larger surface area, accelerating aroma loss and flavor decay. That is why most guidance places longer, more forgiving windows around whole beans—often recommending use within 3 to 6 months of roasting for best results—while ground coffee is best used within 1 to 2 months for peak freshness. Of course, these figures are flexible. If your storage is nearly ideal and you’re not chasing a precise flavor profile, you can still brew decent coffee from beans that are a bit past their prime. The key is to adjust expectations: the cup may lack brightness, and you might notice muted acidity or a more muted aroma. You may even discover that the coffee carries a different character—one that some prefer for a particular brew method, while others might discard it in favor of newer stock.

Given these realities, when should you discard? The simplest rule is to rely on sensory cues rather than the calendar alone. If the beans smell rancid, sour, musty, or off in a way that doesn’t resemble coffee, or if you see mold, discard them immediately. A taste test can also reveal trouble. If the brewed coffee tastes chemically, stale, or unusually bitter with little sweetness left to balance it, it is a sign that the beans have passed their best window. It is worth noting that mild flatness or a muted cracker-dry aroma does not automatically mean danger. It signals a decline in quality and the need to purchase fresh stock if you want a more satisfying cup. For the home roaster and the home brewer, this decision is often a pragmatic one: choose to use the beans for a baking or cooking project if their aroma and flavor have deteriorated, but reserve fresh stock for daily coffee rituals.

The practical art of salvaging older beans lies in adjusting the brewing approach rather than bracing for disappointment. When beans are older but still safe to drink, consider methods that extract more from what remains. A coarser grind can reduce extraction resistance, preventing over-extraction of bitter notes that often become more pronounced as flavor components oxidize. Lowering the water temperature slightly—while ensuring adequate extraction time—can help balance acidity and bitterness that emerge in aged beans. Extending the brew time modestly or trying longer contact methods, such as a longer immersion in a French press or a slower pour-over, can pull out more of the residual sweetness and body. Those tweaks won’t recreate the original aroma, but they can yield a more pleasant cup than a hurried, under-extracted brew from stale beans. Experimentation with grind size, immersion time, and water temperature should be deliberate, guided by a cup that tastes off yet still enjoyable enough to drink rather than discarded at the sink.

The emotional and experiential dimension of expiry also matters. Coffee is not purely a chemical product; it is a ritual, a memory, and a sensory event. The moment you open a bag and release that first, familiar coffee aroma, you’re anchoring to a memory of mornings past. When the aroma fades, the ritual can still be meaningful, but the emotional payoff changes. For many, the decision to discard is tied to that experiential value—whether a cup remains worth the time, effort, and money spent, given the current sensory reality. A cautious approach—checking for odor, visual signs, and taste—serves both the palate and the pantry. It preserves the integrity of your daily ritual without denying the practical reality that flavor shifts with time. In this light, expiry becomes less a moral verdict and more a practical guideline: a compass for choosing freshness, not a verdict on safety.

Ultimately, the relationship between expiry, safety, and flavor is nuanced. Coffee beans that have passed their best-by date may still pose no safety risk if stored correctly and show no spoilage. The trade-off is a cup that has lost some of its sparkle, a nuance of acidity, and an aroma that no longer performs the way it did at peak. The best practice is to use fresh beans when flavor matters most, but when circumstances call for it—when fresh stock is not available or when budget considerations come into play—older beans can still serve a purpose. They can do double duty in coffee drink applications where the aim is not to reveal a bouquet of notes but to deliver warmth, caffeine, and a familiar comfort. Treat expiry as a quality signal rather than a danger warning, and your relationship with coffee can remain practical, flexible, and flavorful—even when the clock on the bag ticks past its printed date.

External reference: For a pragmatic overview of safety considerations tied to expired coffee, see Healthline’s discussion of whether you can drink expired coffee and what experts say about safety and taste. Healthline: Can You Drink Expired Coffee? Here’s What Experts Say

Beyond the Best-By: Mastering Coffee Bean Storage to Keep Flavor Alive

When we talk about whether coffee beans expire, the conversation often veers toward safety and spoilage. Yet the more practical question for most coffee lovers is this: how long will coffee beans taste truly vibrant after roasting, and what can I do to push that flavor window as far as possible? The simple answer is that roasted beans carry a best-by date, not a safety deadline. They begin the gradual slide from bright aroma and nuanced acidity toward a more muted profile the moment they leave the roaster. But that decline is not a cliff. It unfolds in a gentler arc when beans are protected from the elements that speed chemical change. In practical terms, freshness hinges less on a printed date and more on how well you shield the beans from four relentless antagonists: oxygen, light, heat, and moisture. Understanding these enemies helps explain why a bag labeled as still within its date can taste dull, while beans stored with care can surprise you with renewed vibrancy months later. The core idea is simple and actionable: to keep flavor alive, you must seal the beans from air, block light, minimize temperature swings, and keep humidity low. If you can master that, you give yourself a longer, more forgiving peak flavor window, even if the calendar suggests a date is coming up fast.

The flavor degradation that travels with time is mostly a matter of chemistry rather than danger. When beans are roasted, they contain a constellation of volatile aromatic compounds. These molecules are fragile. They drift away in a process called oxidation, especially when air has access to the beans. Within about 30 to 60 days, many roasts begin to lose their brightness—notes that once sparkled as fruity, floral, nutty, or caramel tones fade into a more one-dimensional profile. Acidity softens, the sense of clarity in the cup wanes, and the overall complexity wanes. While the beans remain safe to drink beyond this peak window, the brew may taste flatter, if not frankly tired. The excellent news is that the safety message here is reassuring: coffee beans are low in moisture, a key reason they resist rapid mold or bacterial growth. As long as you avoid damp, warm conditions, you are unlikely to encounter spoilage that would threaten your health. The major risk does not lie in dangerous pathogens; it lies in missed opportunities for flavor because the environment and handling let oxidation, heat, light, and moisture chip away at what makes coffee so delightful in the first place.

To frame a practical approach, it helps to acknowledge the four main enemies one by one and then see how a mindful routine can counteract them. Oxygen is the primary culprit. Coffee beans are created with a fragile balance of oils and aromatics. When oxygen sneaks in, those oils oxidize, producing stale or rancid notes that can manifest as dullness or bitterness. Light acts quickly as well. Ultraviolet rays and even blue-hulled indoor lighting can degrade delicate compounds, altering aroma and flavor long before a cup tastes off. Heat accelerates all of these chemical processes. A warm kitchen shelf or a sunlit counter can turn days into weeks in flavor terms, hastening the march toward a flat profile. Moisture completes the quartet. Coffee’s relatively low moisture content is a shield, but humidity can introduce water into the bean environment, encouraging unwanted reactions and, in extreme cases, mold growth, especially if a bag is compromised or stored in a damp place.

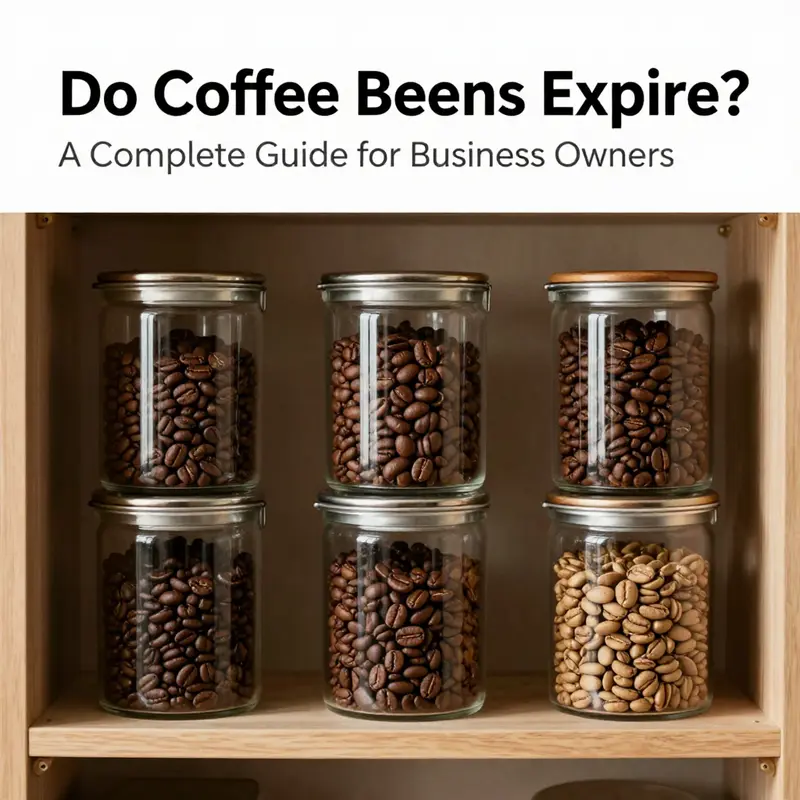

With these challenges in mind, the design of a storage system becomes a compact set of decisions that preserve freshness without turning coffee into a science experiment. The container is the first and most visible choice. The best containers are airtight, opaque, and non-reactive. Opaque materials such as stainless steel, ceramic, or dark glass block light from reaching the beans. A tight-sealing lid helps keep air out and aromas in. The goal is to prevent air exchange without encouraging the kind of airtight suffocation that can trap odors or cause condensation when temperatures shift. In many cases, the original bag the beans came in, especially if it has a one-way valve, can be a good option. That valve is designed to vent the CO2 that fresh beans release while preventing ambient air from rushing back in. For most home storage that does not involve a roaster’s specialty packaging, this valve feature remains a practical and valuable tool. Of course, avoid transparent jars or plastic containers that let light into the bean layer or impart plastic odors through the seal. The oils that carry flavor are sensitive to light stress, and once degraded, they are difficult to restore simply by brewing harder or longer.

Room temperature storage at a cool, dark cupboard is the most accessible and reliable approach for many households. Room temperature does not mean the kitchen counter near the stove or on a windowsill where sunlight and heat can accumulate. It means a cupboard or pantry that stays away from appliances that radiate heat, does not receive direct sun, and remains relatively stable in temperature. When beans are stored this way in an opaque, airtight vessel, the practical effect is to slow the oxidation process enough that the beans retain their character for a meaningful period. If you typically brew within two to four weeks of purchase, this method often yields excellent results. You may notice the flavors smooth out slightly as the beans settle, a natural progression that some coffee lovers actually welcome, because it mirrors the natural maturation of roasted coffee in a more controlled environment. The beans do not need to be hidden away forever; they simply benefit from a calmer atmosphere where air, light, heat, and moisture stay at bay.

Freezing is a tool for larger quantities or for long-term storage when you cannot consume beans within a few weeks. Freeze only if you have a clear plan for usage and you follow strict precautions. The key is to freeze in a completely airtight, vacuum-sealed environment. Any exposure to air or moisture can compromise the beans when they are thawed. Importantly, avoid refrigeration as a long-term storage home for coffee beans. Refrigeration cycles can cause condensation when you move beans from cold to room temperature, inviting moisture-related off-flavors and even mold. If you decide to freeze, divide the beans into small portions, perhaps around 100 grams each, and seal them in individual vacuum bags or airtight containers. When you need to use a portion, remove it from the freezer and let it thaw fully at room temperature before opening the bag. Only then do you release the seal, allowing the beans to come to ambient conditions gradually. This careful approach minimizes condensation on the beans themselves. Freezing should be a last resort for most home users because the processes involved can introduce complexity, and daylight, heat, or moisture exposure during thawing can erode the very benefits you hoped to preserve.

Of course, even with the best storage practices, there are common missteps that creep into routine. A frequent mistake is buying larger quantities than you can reasonably use within the ideal freshness window. The temptation to stock up on a generous supply often backfires when the clock on flavor has moved past its peak. Relatedly, grinding is a major flavor pitfall. Ground coffee reacts with oxygen far more quickly because its increased surface area accelerates oxidation. The rule of thumb is simple: grind just before brewing. Pre-ground coffee almost always betrays the best effort of a good roast. Another practical misstep is neglecting to purchase beans in sizes appropriate for your usage rate. A 1-kilogram bag can seem economical, yet if you only brew a few times a week, much of that bag will age beyond its peak, losing its memorable character. The simplest solution is to buy smaller quantities more frequently, a cadence that aligns with your actual consumption and allows you to experience beans closer to their peak aromas.

From a more technical perspective, the lifecycle of roasted beans informs how we approach expiration dates. The industry standard shelf life of 12 to 18 months, under proper storage, outlines a broad safety and quality window. But the practical peak flavor window tends to be tighter, with aromatic nuance at its richest within the first few weeks and tapering after about a month or two for many roasts. This is not a mandate to discard after a date; it is a caution that flavor quality will decline with time, and the rate of decline is mitigated most effectively by controlling exposure to air, light, heat, and moisture. The date printed on a bag acts as a guide for flavor, not safety. Roasted beans’ resilience against spoilage is comforting, yet it also invites a discipline of mindful usage. If stored properly, you can trade some of the initial sparkle for convenience, without sacrificing the chance to brew a satisfying cup.

A pivotal part of any storage philosophy is recognizing when flavor has passed its prime. Signs to watch for include a faded aroma that no longer invites you to sniff the grind, a muted or dull acidity when you taste, and a general lack of complexity in the cup. An overlooked cue is the sense of aroma after grinding and pouring hot water; the strength of the initial scent can foreshadow the cup’s brightness. More alarming are overt signs of spoilage—visible mold, a musty or sour smell, or a rancid note when brewed. While mold is rare with dry beans, it is not impossible in the right conditions, such as damp, warm storage. In those cases, discarding the beans is the safest course, even if they look fine at a glance. You should always trust your senses: if the beans look dull, smell off, or taste disagreeable, it is wiser to discard them and brew anew with fresher stock.

An important thread in this discussion is the practical relationship between what a date means and what a consumer can achieve in daily life. The best-by date is a flavor forecast, not a safety marker. The underlying chemistry of coffee indicates a robust life for safety beyond that forecast, but with a caveat: the quality of the experience depends on your storage discipline. In other words, the calendar is a guide; your storage routine writes the real story of how long a batch of beans stays expressive in your cup. If you combine a well-sealed, opaque container with a cool, dark storage spot, a sensible consumption pace, and occasional disciplined use of freezing as a fallback, you extend your ability to enjoy a sufficiently lively cup well past the initial days after roasting. You don’t need to chase a perfect, museum-like freshness; you simply need to align your practices with the physics of flavor and the rhythms of your own coffee habits.

The practical takeaway is straightforward. Treat of the storage environment as the steward of flavor. Use a container that blocks air and light, keep the beans in a cool, dark place, grind only as you brew, and stay away from the temptations of overly large quantities. If you anticipate longer storage than a couple of weeks, consider freezing in tightly sealed portions, ensuring full thawing at room temperature before opening. Remember that the primary risk to flavor is exposure to air and heat; the safety risk is minimal, but taste risk is real. In most homes, output hinges on routine rather than miracle solutions. A calm, deliberate approach—to seal, shade, and temperature stability—will yield a cup that remains intriguing, even as the calendar advances.

To help frame this in real-world terms, it is useful to tie these ideas back to the broader concept of expiration versus freshness. The roasted coffee bean’s shelf life is a guide to the period during which the beans retain their peak aroma and complexity, not an indicator that the beans will suddenly become poisonous after a date. With proper storage, the difference between a bean that’s 2 weeks old and one that’s 8 weeks old can be subtle, especially if you are mindful of grind size and brew temperature. On the other hand, a bag left unprotected for months will reveal the truth in the cup: diminished brightness, flatter acidity, and a less dynamic mouthfeel. The chapter’s focus remains practical: minimize the four enemies—oxygen, light, heat, and moisture—and you preserve the bean’s expressive potential for longer than you might anticipate.

If you want to push the envelope further, consider the living dynamics of your kitchen. A pantry that stays consistently cool, away from sunlight and humidity, serves you far better than a sunlit shelf or a cabinet above a stove. Likewise, a dedicated storage vessel that you use exclusively for coffee helps prevent cross-odors from creeping in. The aroma of coffee, though often celebrated, is a shared experience with the surrounding air. The more you can shield it from neighboring scents, the more the true character of the roast remains discernible when you grind and brew. That means avoiding storing coffee near strong-smelling spices or cleaning products that can impart unwanted notes to the oils in the beans. While these details may seem minor, they accumulate across days and weeks, shaping your daily cup in ways that might surprise you if you let them.

In the end, the question of whether coffee beans expire touches two realities: the science of flavor and the pragmatics of daily life. The science says flavor fades as oxidation and other chemical processes progress, with peak flavor staying within reach for a limited period after roasting. The pragmatics say you can stretch that period through disciplined storage, thoughtful portioning, and prudent use of freezing when needed. The result is a coffee experience that remains engaging longer than a simple best-by date would suggest, without crossing into the realm of risk or safety concerns. This balanced view respects both the craft of roasting and the rituals of brewing, acknowledging that freshness is not a fixed attribute but a dynamic quality that you steward through everyday choices.

For those who want a concise, practical summary of the steps that matter most, here is the essence: choose an airtight, opaque container; store in a cool, dark place; avoid grinding until just before brewing; and limit long-term storage by buying quantities you can use within a few weeks. If you must store longer, freeze small portions in vacuum-sealed packaging, and thaw only when ready to brew. These choices, carefully applied, allow you to enjoy a cup whose aroma and brightness remain more of a celebration than a compromise, even as time passes. The journey from roast to cup is a chemistry lesson in patience as much as a ritual of delight. And by respecting the four enemies—oxygen, light, heat, and moisture—you give your coffee beans a better chance to deliver their best possible behavior when they finally meet the water.

External resource: https://www.seriouseats.com/ultimate-guide-to-storing-coffee-beans

Final thoughts

In conclusion, while coffee beans possess a shelf life characterized by ‘best-by’ dates that relate primarily to flavor and freshness, they don’t pose a safety risk after this period, provided they’ve been correctly stored. Flavor degradation is a natural process that affects the taste profile of coffee beans over time, making it vital for businesses to recognize the importance of proper storage methods. Keeping beans in a cool, dry, and dark environment ensures they maintain their desired qualities for as long as possible. By understanding these aspects, you can confidently manage your coffee inventory, ensuring the best experience for your customers while minimizing waste.