For business owners in the coffee industry, understanding the nuances of coffee preparation can significantly influence product quality and customer satisfaction. The choice of grinding coffee beans is particularly crucial, as the grind size can dramatically affect the brewing process and, ultimately, the flavor profile of the cup. Blenders often serve as a convenient tool for grinding coffee beans, but they may not deliver the consistency needed for high-quality coffee. This article explores three pivotal considerations: inconsistent grind size, heat generation effects, and control limitations when using a blender for grinding coffee beans. By delving into these aspects, business owners can make informed decisions about their coffee preparation methods.

The Case for Uniformity: Why a Blender Struggles with Consistent Coffee Grinds

The Case for Uniformity: Why a Blender Struggles with Consistent Coffee Grinds

Blender Grinding and the Heat Gamble: Preserving Coffee Flavor When You Grind Beans

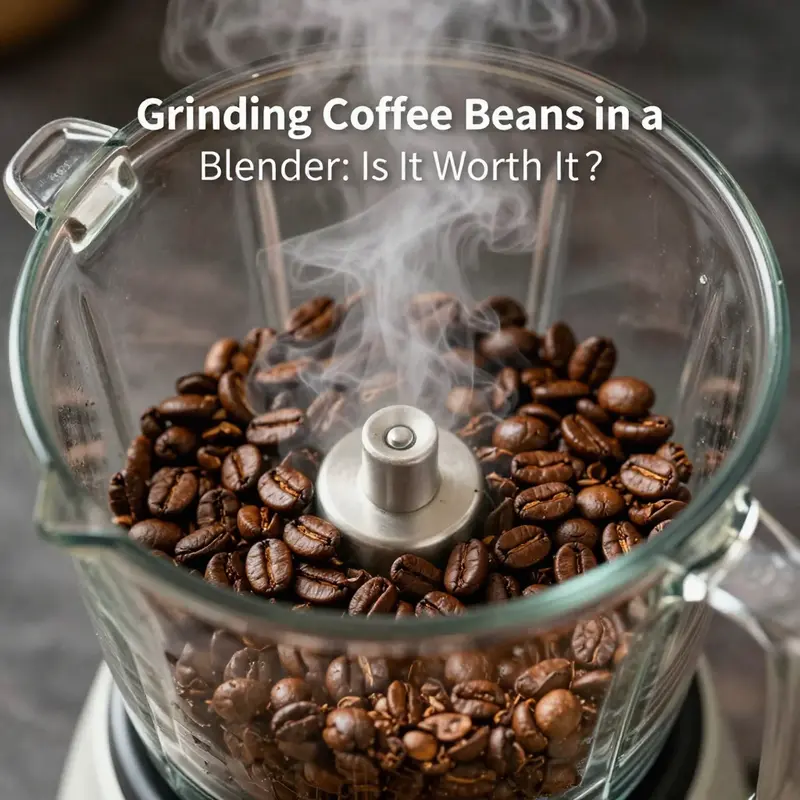

The question of whether a blender can grind coffee beans is familiar to anyone who has found themselves staring at a bag of beans while missing a dedicated grinder. The impulse is simple: if you own a blender, why not use it in a pinch? Convenience is a powerful lure, and the blender has a familiar, all-in-one promise. Yet the research of flavor and grinding physics gives a clearer view of what happens when those high-speed blades meet coffee beans and the heat that accompanies the process. The blender is not designed to grind coffee; it is designed to blend, emulsify, puree, and pulverize ingredients with an eye toward speed and uniformity for drinks, soups, and sauces. When you apply that purpose to coffee, you encounter a set of trade-offs that can subtly or dramatically shift the final cup. The core tension lies in heat, grind consistency, and control. Each of these factors interacts with the others, shaping aroma release, extraction during brewing, and the perceived balance of sweetness, acidity, and bitterness.

Heat is the most immediate and perceptible consequence of grinding coffee in a blender. The blades rotate at high speeds, generating friction as they shear through the dense, resinous structure of roasted beans. That friction translates into heat, and even brief grinding sessions can warm the coffee grounds. In a world where aroma compounds are the currency of quality, warming matters. Many of the delicate volatile compounds that give coffee its signature bouquet—floral notes, citrus, berry brightness, and the elusive bouquet that hints at a freshly baked pastry—are fragile. They begin to evaporate or transform as temperatures rise. The result is a cup whose fragrance is diminished even before it reaches the brewing stage, and whose flavor palette can tilt toward the more bitter or overstressed end of the spectrum if over-processed by heat.

Flavor degradation from heat is not merely about sweetness or tang; it is about the very structure of aroma. Coffee is a complex matrix of oils, acids, and a spectrum of volatile molecules that communicate with our senses in a chorus. When heat is introduced during grinding, some of these volatile molecules volatilize or rearrange, while certain oils can become prematurely released and then partially oxidize. The net effect is a ground coffee that smells less bright and tastes less nuanced. Instead of a crisp, layered aroma that opens up as you brew, you might encounter a more one-note profile or a slightly burnt impression. That burnt note is not the same as a scorching roast; it is more like the taste of oils heated beyond their optimal stability—the kind of edge you notice when a cup feels flat or overly toasty in the finish.

Another consequence of heat in a blender is the difficulty it creates in achieving a uniform grind. The ideal grind size for coffee is not a single number; it is a range that aligns with your brewing method. Espresso demands a fine, even powder; French press requires a coarser texture with some porosity; pour-over benefits from a uniform medium grind that allows even extraction. A burr grinder excels precisely because it creates predictable, reproducible particles and minimizes heat buildup during grinding. A blender, with its blunt approach and high shear, tends to produce a mix of coarse and fine particles. You end up with a heterogeneous grounds bed, which means inconsistent extraction. Some particles flood with water, yielding weak, under-extracted flavors, while finer particles compact and resist water flow, contributing to over-extraction and bitterness. The result is a brewed cup that can veer toward a muddy body or a sharp, dry finish, depending on the ratio of fines to larger fragments and how quickly the water navigates the bed of grounds.

These physics-based realities have practical consequences for the way we approach grinding in a blender. Short pulses, small batches, and cooling pauses can mitigate some heat buildup, but they do not fully compensate for the fundamental lack of control that a dedicated grinder provides. The lack of precise particle-size control matters because the extraction kinetics of coffee are highly sensitive to surface area and porosity. In a blender, you may never quite know whether the majority of your grounds are as fine as dust or as coarse as grit, and that ambiguity translates into variable flavor from cup to cup. This inconsistency can be frustrating for anyone who has invested in coffee for flavor clarity, aromatics, and a clean cup.

The best-case scenario for blender grinding is not a flawless replica of a burr-ground grind but a tolerable compromise. If you find yourself in a situation where a blender is your only option, there are mindful practices that can help preserve flavor and minimize the heat penalty. First, work in small batches. A modest amount of beans will heat less during the short grinding bursts than a full container will. Second, use short pulses rather than continuous blending. Pulsing reduces the average blade speed over time and introduces micro-rest periods that allow some of the heat to dissipate. Third, monitor the grind texture with frequent checks. Grinding until you observe a consistent size is less practical in a blender than in a burr grinder, but you can still aim for a uniform range by pausing to inspect and re-blend if needed. Fourth, cool the grounds intermittently. Spreading the grounds on a cool surface for a moment or transferring them to a cooler container can help reduce heat buildup before brewing begins. And fifth, be mindful of the brewing method. The compromises of blender grinding are not equally costly for every method. A pour-over or drip brew may tolerate a somewhat uneven grind better than a precise espresso shot, where finish quality hinges on a tight extraction profile.

Jumping from theory to practice, it becomes clear that the blender’s heat is a practical limit on flavor preservation rather than a fatal flaw in capability. If you are new to coffee and exploring the hobby, managing expectations is essential. The blender can deliver a coarse, workable coffee powder, enough to produce a drink that is drinkable and satisfying on a casual day when other tools are unavailable. For many home roasters and casual coffee drinkers, this is a temporary workaround rather than a recommended long-term strategy. The sensory difference between a cup brewed from blender-ground coffee and one ground with a burr grinder is not merely academic; it translates into a tangible taste and aroma gap that becomes more noticeable as you refine your palate and compare multiple brews side by side.

For the curious reader who seeks a more granular understanding of the heat phenomenon and wants to balance the desire for convenience with flavor integrity, it helps to consider the broader framework of grinding tools and their intended purpose. Blenders are optimized for speed and uniform liquidization, not for preserving the delicate chemical balance that defines specialty coffee. The recommendation that emerges from the research is neither harsh nor dogmatic: use a burr grinder when possible, or a purpose-built blade grinder that is optimized for coffee and designed to minimize heat transfer. In a pinch, a blender can work, especially if you employ very deliberate technique—short pulses, small batches, frequent checks, and cooling routines. The key is to recognize the boundary between acceptable short-term improvisation and long-term habit that may erode the coffee’s flavor potential over time.

From a sensory perspective, the difference is not just about a single note being off. It is about the orchestra of flavors—the brightness of acids, the depth of roasted sweetness, the caramel and chocolate undertones, and the way aroma blossoms in the cup as it cools. When heat from grinding reduces volatile compounds, those notes recede, and the cup can feel flatter, lacking the lift that a well-pulled pour or a properly timed extraction provides. The brew becomes a proxy for what the beans might have offered at their peak, rather than a true reflection of the roast and the bean’s intrinsic character. This is not merely a matter of personal preference; it is a matter of chemistry and physics playing out in the kitchen, reminding us that the tools we choose shape the results we experience.

For those who want to compare blender grinding with a more precise method, the evidence is clear. A burr grinder remains the standard bearer for consistent grind size and temperature management. It creates narrow particle-size distribution, which translates into predictable extraction curves and a cleaner cup. A dedicated blade grinder, specifically designed for coffee, often serves as a practical compromise when a burr grinder is out of reach. It can deliver a more controlled grind with less heat than a high-speed blender, though it still cannot match the precision of a burr mechanism. The bottom line is that heat generation is not an abstract concern; it is a tangible variable that colors the entire brewing process, from extraction kinetics to the final aroma and palate. When you accept this, your approach to grinding becomes more strategic rather than merely expedient.

The social and psychological dimensions of grinding coffee in a blender also deserve a moment of reflection. There is a sense of improvisation and spontaneity in turning to a blender when a dedicated grinder is not at hand. That moment can be empowering, a creative workaround that keeps a morning routine intact. Yet this improvisation should be tempered with an awareness of the potential trade-offs. If flavor quality matters, or if you are preparing coffee for guests or for a tasting session, the cost of heat-induced aroma loss and uneven extraction might be more noticeable. In such moments, a quick reset—cool beans, small batches, and a careful pulse sequence—becomes more than a practical trick; it becomes a mindfulness practice about how we treat ingredients and how we value the sensory outcomes of our brewing chemistry.

As a practical note, the conversation about heat is also a broader reminder about how tools constrain or enable our culinary and sensory ambitions. The blender’s heat is not the villain; it is a design reality that requires a more deliberate approach if we insist on using the device for coffee grinding. If you want to explore a structured path toward improved control, you might look at resources that discuss how practitioners approach precision and repeatability in tasks that require fine motor control and careful timing. For readers who enjoy cross-disciplinary perspectives, the related material on hands-on exercises and adaptive techniques offers a useful parallel to how coffee preparation can benefit from methodical practice and disciplined pacing. occupational-therapy-exercises-for-adults.

The overall conclusion that emerges from the blended evidence is a balanced one. A blender can grind coffee beans, yes, but it does so with a heat-influenced consequence profile and a grind texture that is far less predictable than the profile provided by a burr grinder. If your priority is flavor precision and consistency, a dedicated grinder is the sound investment. If you find yourself without a grinder and need something workable for a single cup, a blender can serve as a stopgap, provided you adopt a contrived routine: grind in small batches, pulse briefly, monitor the grind texture, and keep the process cool to preserve as much aroma as possible. The flavor payoff is inherently uncertain in this scenario, but the practical value of a usable cup remains, especially on mornings when time or equipment constraints demand ingenuity.

In framing the larger article—can you grind coffee beans in a blender?—this chapter reinforces the central message: tool choice matters for flavor outcomes, but knowledge about the process can help you navigate constraints. The blender is not ideal, but in a pinch, with discipline and careful technique, it can produce acceptable grounds for brewing. The trade-offs are real, and the decisions you make about batching, pulsing, and cooling are the levers that determine how much of the bean’s terroir you retain in the cup. For those readers who value a transparent, evidence-informed discussion, this perspective aligns with the broader understanding of how grinding technologies influence extraction dynamics, aroma preservation, and the final sensory experience. And for the curious minds who want to explore the topic further from related angles, the linked resource offers a broader context on how grinding methods compare in practice, reinforcing that heat management and precision are central to achieving a satisfying cup, regardless of the chosen device.

External resource: https://www.thespruceeats.com/coffee-grinding-blender-vs-grinder-1879567

Control Limits and Cup Quality: Why a Blender Struggles to Grind Coffee Beans Consistently

A blender is often the first impulse of convenience when beans need to be prepared quickly. The impulse feels reasonable: it whirs, it chops, it seems to produce something that resembles ground coffee in a matter of seconds. Yet the moment you attempt to translate that quick grind into a reliable cup, the cracks appear. The blender, designed for mixing and chopping rather than for disciplined particle control, presents a set of stubborn limitations that ripple from grinder mechanics to cup flavor. The conversation about grinding coffee beans in a blender is not merely about a single technique; it is a discussion about how the right tool, controlled by the right parameters, shapes the very texture of flavor before you even brew. If you are chasing a balanced brew—whether for a delicate pour-over or a stubbornly intense espresso-like shot—the blender’s limitations tend to show up in the cup as uneven extraction, inconsistent aroma, and a sensation that the coffee refuses to behave the way you expect.

At the heart of this challenge lies particle size distribution. In coffee terms, consistency is king. For a robust extraction, you want a uniform bed of particles that lets hot water flow through at a steady pace, with every fragment meeting the water at a similar surface area. A burr grinder does this by design. It crushes beans into evenly sized pieces, producing a spectrum of particles that a skilled barista can anticipate and compensate for with technique. A blender operates with a very different purpose in mind. Its blades spin rapidly, flinging material outward through collision and shear. The result is a chaotic mix: some fragments grind into fine dust, others remain as larger, uneven shards. That chaos matters because during brewing, water meets those particles at different rates and for different lengths of time. The fine dust can over-extract, pulling bitter notes and astringency from the beans. The larger pieces can under-extract, leaving a sourish tang or a flat mouthfeel that lacks the liveliness we associate with a well-made cup. In practical terms, this translates into a cup that tastes inconsistent from brew to brew, even when you think you have replicated the time and method with care.

Heat is another stealthy adversary of grind quality. High-speed blades generate heat through friction. A momentary surge of heat can alter delicate flavor compounds and shift the oil profile liberating from the grounds. Some of those aromatics—bright esters, fruity nuances, or nuanced floral notes—can evaporate or transform under heat stress, leaving the cup flatter than intended. The flavor changes may be subtle, but in the world of coffee, those subtle shifts matter. When baristas and home brewers talk about flavor clarity, they are often describing how cleanly a coffee presents its aromatic spectrum. A blender’s heat tends to blur that spectrum, reinforcing the sense that the cup is more about bitterness or dullness than it is about bright or nuanced characteristics. This is not merely a matter of degrees of flavor; it is a question of how aroma compounds and volatile oils survive the grinding process long enough to be captured by the brew. That is why many sources frame the blender as an acceptable, not ideal, option—useful in a pinch, not the go-to for serious coffee quality.

Control matters more than most people expect. A burr grinder enables you to dial in grind size with precision tailored to the brewing method. For espresso, the grind is fine and compact; for pour-over, it is medium; for French press, it is coarser, allowing a longer contact time without clogging. A blender, by contrast, offers a binary sense of “coarse” or “fine,” with little room for the gentle graduations that brew methods demand. Even when you attempt to compromise with pulse intervals or constant stirring, the underlying dynamics remain fundamentally less predictable than a burr grinder’s mechanical stability. The empty promise of control—“I can set this to medium” or “I can pulse in shorter bursts to avoid heat”—crashes against the reality that blade systems are not designed for even particle creation. That disconnect is the core reason the blender struggles to deliver consistently balanced extraction across different brews.

This is not to deny that a blender can produce usable coffee, especially when speed is essential and the margin for error is large. It is to acknowledge that the margin for error is what separates the casual, acceptable cup from a more precise, repeatable experience. In a pinch, you can attempt to harness a blender’s potential with disciplined technique: use short pulses rather than continuous runs; stop intermittently to check the particle size; let the machine rest to avoid overheating; and rinse and recheck the grind frequently as you approach the target consistency. You might also consider pre-grinding in fractions, then combining those fractions to approximate a steady grind, though this is rarely a perfect workaround. The main aim remains to minimize heat generation and to maximize uniformity in particle size, two goals that blade-driven devices struggle to meet when pressed into the service of coffee grinding.

One useful way to frame the blender debate is to compare it to a broader design philosophy: when a tool is optimized for a general-purpose task, it often cannot deliver the reliability required for a specialized result. This is a lesson not only for coffee gear but also for any task that depends on consistent material behavior. In the broader context of home labor and instrument use, it is a reminder that some activities demand what practitioners call a “controlled environment.” In coffee, this means a stable grind with predictable extraction. In a workshop or studio, it means a process that can be repeated with precision. The blender’s strength lies in its versatility and speed, not in its capacity to provide a uniform feed for water. The result is a cup where the zest of origin and roast can get overshadowed by the uneven texture and the unpredictable pace of extraction.

This nuanced understanding is not merely academic. It informs the practical choices a home brewer makes. If you own a blender and are curious about its performance for coffee, approach the process with humility and clear expectations. The first step is to acknowledge the limits: you are trading precision for speed. The second step is to implement a disciplined protocol that explicitly addresses the blender’s tendencies: short bursts to minimize heat buildup, frequent checks to gauge particle size, and a willingness to pause and reassess after producing a sample. The third step is to be mindful of brew method requirements. Espresso demands a uniform, fine grind with controlled pressure and extraction; pour-over requires a uniform medium grind to achieve even saturation; French press tolerates a coarser texture but still benefits from some degree of uniformity for steady extraction. The blender’s limitations are magnified precisely where these methods press for control. Understanding that helps a home brewer decide when a blender is a practical choice and when it is a compromise that may not justify the trade-offs in taste.

To anchor these ideas in a broader practice of tool selection, consider the parallel in occupational contexts where professionals weigh technique against tool. In this chapter’s adjacent domain—skills required to execute daily tasks reliably—the principle remains consistent: technique can sometimes compensate for instrument limitations, but not indefinitely. This is where the internal discussion around techniques used in occupational therapy becomes instructive. The emphasis on method, sequence, and careful adjustment resonates with how a coffee enthusiast should approach grinding with a blender. If you want to explore that discipline’s approach to method and adaptation, you can read about the broader range of techniques used in occupational therapy, which emphasizes careful control of process and outcomes. Techniques Used in Occupational Therapy.

From a practical stance, there is a natural curiosity about what a blender can still do well in the realm of coffee. If you accept the trade-off and proceed with a blended grind, there are concrete steps that can improve the likelihood of a decent cup. Begin with small, controlled pulses—no more than a second at a time—allowing a short rest between bursts to dissipate heat. Stop as soon as you notice the grind becoming dust-like in some portions, but chunky in others. Rather than letting the blender run until you reach a target, you are guiding a process that remains inherently imprecise. It helps to test-brew in small quantities, tasting and adjusting your expectations with each iteration. If you are aiming for pour-over, you might find a rough, medium grind that flows through the filter with a moderate but steady rate, albeit with a higher degree of friction and a slight risk of channeling. For French press, the blend may attempt to approximate a coarser texture, but the extraction will still tend to be uneven, producing a cup that can lean toward muddiness rather than clarity. The key is to focus on process more than the illusion of control and to accept the cup as a product of an imperfect operation rather than a precise craft.

The research results behind the blender’s limitations are consistent across many accounts: the lack of control over particle size, the inability to adjust grinding variables, and the resulting poor uniformity in extraction. These are the core reasons most professional and informed home baristas reach for a burr grinder as a first choice. A burr grinder’s constant-geometry design reduces variance, keeps heat at bay, and enables a sequence of adjustable steps that align with brew methods. The chapter’s sources emphasize that the best path to quality is precise, uniform particle sizing and minimized thermal influence. In other words, the blender remains a compromise rather than a tool of choice for serious coffee practice. Yet the fact that it can work in a pinch is important too. The reality is you can, with care, move a blender toward an acceptable outcome, but you must respect its limits and treat the grind as a stepping-stone rather than a final, repeatable standard of flavor.

In closing the practical arc of this discussion, consider the journey from bean to cup as a chain of decisions about control, timing, and temperature. Each link in that chain is susceptible to the influence of your grinding method. A reliable burr grinder closes the loop with precision, giving you a repeatable platform on which to build your brew method and roast profile. A blender tests the resilience of your palate and your patience, challenging you to coax consistency from a tool not designed for it. The difference is not only technical; it is also a matter of taste philosophy. Do you want a cup that reflects a controlled, repeatable process, or do you want a cup that acknowledges the human element of improvisation, where warmth, speed, and a dash of unpredictability shape the final experience? Either path can yield a satisfying drink, but the blender’s path is a story of compromise, not perfection.

If you are intrigued by the broader conversation on how tools influence outcomes beyond coffee, it is worth exploring other disciplines that wrestle with similar questions about control and technique. The idea that technique and process can sometimes compensate for imperfect tools is echoed in many crafts and care practices. For readers who want to explore a parallel discipline, the discussion of techniques used in occupational therapy offers a complementary lens on how professionals balance tool capability with method, sequence, and patient-centered outcomes. This cross-disciplinary perspective helps remind us that in any skill, from grinding to therapy, the path to quality is navigated not by tool alone but by the discipline of technique and the humility to recognize limits. For readers who crave a deeper dive, the external resource linked below provides a broader view of the careful, technique-forward mindset that those in therapy cultivate as they support practical daily activities with adaptive strategies and mindful practice. See the external reference for more context on method-led outcomes: https://www.theprocoffee.com/why-you-should-never-use-a-blender-to-grind-coffee-beans/

In sum, grinding coffee beans in a blender can be a practical stopgap, but it comes with a clear price: uneven particle size, heat-induced flavor shifts, and limited control that undermine consistency across brewing methods. A burr grinder, preferably with a set of grind sizes calibrated to your preferred brew method, remains the preferred instrument for home baristas who care about flavor balance, aroma retention, and extraction smoothness. If the blender must stand in for a moment, treat it as a temporary bridge rather than a final solution, and let the cup you chase be shaped by the awareness that some corners of the kitchen demand a steadier hand and a more deliberate plan. The right approach is to pair thoughtful technique with the right tool, and to acknowledge that the most satisfying cups often grow from a careful craft rather than a convenient shortcut.

Final thoughts

In conclusion, while it is technically possible to grind coffee beans in a blender, business owners should be aware of the limitations related to inconsistent grind size, heat generation impact, and lack of control over the grinding process. Understanding these factors can help coffee entrepreneurs make better decisions about their equipment and the quality of coffee served to customers. Investing in a dedicated coffee grinder, particularly a burr grinder, is likely to yield superior results and improve customer satisfaction across the bustling coffee landscape.