The world is full of challenges, and the need for compassionate support has never been greater. Various professions focus on uplifting individuals and communities, creating a ripple effect of positive change. Understanding these roles can inspire business owners to engage meaningfully with their communities, whether through partnerships, volunteering, or dedicated corporate social responsibility. This comprehensive look at jobs related to helping people will delve into social work, education, healthcare, community organization, and counseling, showcasing how each plays a vital role in fostering a supportive and resilient society.

null

null

Educating the Helpers: How Learning Shapes Compassionate Careers That Uplift Others

Education serves as the quiet architect behind every act of service. It is not merely a credential or a checklist of courses; it is the framework that shapes judgment, calibrates skill, and nurtures the empathy that turns knowledge into help. When we speak of jobs that help people, we are talking about roles where outcomes matter—where decisions ripple through families, communities, and futures. In such work, learning is both compass and toolkit: it orients practitioners toward ethical choices and equips them with the concrete competencies needed to implement those choices in real life. Consider nursing, social work, teaching, psychology, or community organizing. Each field rests on a bedrock of discipline and method—anatomy and pharmacology, theories of development and learning, assessment techniques, and evidence-based practices—yet it is the human dimension that makes the outcomes meaningful. Without rigorous education, the capacity to heal, to mentor, to advocate, or to sustain a community fades into well-meaning sentiment rather than durable impact.

Across the spectrum of helping professions, formal study opens a doorway to understanding what it means to care well. A nurse must master physiology and patient safety protocols, but equally crucial is the ability to listen to a patient’s concerns, to explain a treatment plan in accessible language, and to work within a team that respects every voice at the bedside. A school counselor needs training in child development and mental health assessment, but also the discernment to recognize when a student’s struggles are rooted in trauma, poverty, or social inequity. A social worker must grasp policy, resource navigation, and the ethics of confidentiality, while also cultivating the resilience to bear witness to painful stories and to respond with steadiness. Education in these fields blends science with humanity, ensuring that professionals are not merely skilled technicians but trustworthy partners in people’s lives.

Beyond the acquisition of knowledge, the most transformative aspects of education lie in how it cultivates character. Ethical judgment, a respect for diverse backgrounds, and the capacity for tough conversations are not easily taught through lectures alone. They emerge through case discussions, role-plays, reflective writing, and supervised practice where mentors observe, critique, and encourage growth. In this sense, education becomes a social contract. It promises that those who choose helping roles will approach others with dignity, consent, and humility, even when the situations are complex or emotionally charged. This is especially critical when serving vulnerable populations who depend on caregivers to honor autonomy and to uphold rights while offering compassionate support. The discipline of studying how to communicate across cultures, or how to navigate consent in sensitive health decisions, translates into encounters that preserve safety and trust in real life.

Experiential learning is the bridge between theory and practice. Internships, clinical placements, and service-learning projects put students into environments where theory meets the friction of everyday life. A social work student might spend a semester in a shelter, witnessing how housing instability intersects with health, education, and employment. A nursing student rotates through hospital wards, learning not only procedures but also the rhythms of patient care—the pacing of wards, the timing of rounds, and the delicate balance between efficiency and presence. A future teacher gains not only instructional strategies but also firsthand experience with students who learn differently, which informs how to design inclusive classrooms. These authentic experiences deepen understanding and shift education from a repository of facts to a living practice, where students learn to adapt, improvise, and persist in the face of obstacles.

Policy discussions in recent years, including the 2025 OECD report on Future-Ready Education, reinforce the idea that schools must connect learning to real-world service. They argue for career-focused learning early on, where young people can explore helping professions through project-based activities, mentorship, and deliberate exposure to community needs. The aim is not to steer every student toward a single path but to illuminate a spectrum of possibilities and to help each learner see how their values align with a vocation that serves others. When curricula integrate service experiences with reflective study, students move from asking what a job pays to asking how they can contribute to a more just and humane society. This reframing matters because it aligns personal meaning with professional competence, sustaining motivation across the oft-challenging realities of frontline work.

Education, then, does more than prepare individuals to perform tasks. It shapes a mindset—an orientation toward lifelong learning, ethical stewardship, and collaborative problem-solving. It teaches how to question assumptions, how to listen deeply, and how to translate understanding into action that respects human dignity. In disciplines like nursing, psychology, and teaching, a strong foundation is indispensable; but it is the cultivation of empathy and the refinement of judgment that enable professionals to respond with compassion when systems fail or resources are scarce. The result is a workforce capable not only of delivering care or instruction but of nurturing resilience within communities. This is where education becomes a public good: it multiplies the capacity to help, not simply by adding more hands on deck, but by ensuring those hands are guided by knowledge, ethics, and empathy.

Within this ecosystem of preparation, mentorship and experiential learning remain essential accelerators. A teacher who mentors a cohort of student teachers can model inclusive practice and collaborative planning, translating theory into classroom realities. A nurse who reflects on a demanding shift with a supervisor gains insight into patient-centered care and risk management. A social worker who partners with a field placement supervisor learns to balance advocacy with professional boundaries, developing a practical ethic of service that sustains long-term engagement rather than burnout. Such experiences do more than refine skill; they embed a practitioner in a culture of care. They teach the value of humility—recognizing what professionals do not know, seeking guidance, and continually updating one’s practice in response to new evidence and shifting community needs. In a sense, education trains the eyes that see problems clearly, the hands that can do something about them, and the heart that remains steadfast when the work becomes arduous.

For readers considering their own path, the landscape of helping professions is both broad and intimate. It invites exploration, not coercion, and it rewards commitment to growth over bravado. A practical route begins with curiosity about what roles resonate with one’s strengths and values. The path often weaves through formal study and practical experience, converging at the intersection where knowledge, capability, and compassion meet. To glimpse the breadth of possibilities, one can explore the array of options that exist for those who wish to help others. For a broader glimpse of the paths people follow to help others, consider the range of options in 17-careers-for-helping-people.

Ultimately, education in service-oriented fields aspires to more than employment. It aims to cultivate professionals who can view a person’s life as a complex network of needs, resources, and possibilities. This perspective underpins a commitment to ongoing learning, because needs evolve and new evidence changes how best to respond. The combination of rigorous science and humane practice—of precise technique and nuanced understanding—produces professionals who are equipped to handle uncertainty with steadiness and to advocate for systems that better serve all people. As societies confront public health challenges, educational disparities, and social inequities, the demand for well-prepared helpers becomes more urgent, not less. Education, in its most meaningful form, prepares people to meet that demand with competence, courage, and care. It makes compassionate action deliberate, informed, and sustainable, ensuring that the impulse to help endures as a practiced craft rather than a fleeting instinct.

External resource: OECD Future-Ready Education: Preparing Students for Jobs That Help People — https://www.oecd.org/education/future-ready-education-2025.pdf

Care in Motion: Healthcare Professions as the Heartbeat of Helping People

Care in Motion: Healthcare Professions as the Heartbeat of Helping People

The work of helping people through healthcare is a story told in small, daily acts as well as in decisive, life-changing moments. It is written not only in medical charts and exam rooms but in the quiet habits of listening, empathy, and steady presence. This chapter follows that thread across direct patient care, rehabilitation, prevention, public health, and the systems that organize care. It asks not only what these roles do, but why they matter to communities and to the people who inhabit them. The most urgent acts—the rescue in a moment of danger, the steady support that keeps a patient from sliding back into crisis—are built on a foundation of routine, ongoing care. In healthcare, helping people is both a spectrum of tasks and a shared discipline—one that depends on skill, humility, teamwork, and a relentless focus on dignity and equity.

Direct patient care sits at the core of this spectrum. Home health aides provide essential daily support for elders and disabled individuals, helping with activities of daily living, monitoring well-being, and enabling people to remain in familiar surroundings. In clinics and hospitals, nurses deliver ongoing, comprehensive care, balancing technical procedures with the human needs that underlie every clinical decision. Paramedics and emergency medical technicians answer quickly when crises arise, transporting patients to safety and stabilizing conditions long enough for treatment to begin. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners extend the reach of physicians, performing examinations, diagnosing conditions, and often prescribing care that keeps people out of more serious trouble. Each role carries a different arc of training, yet all share a unifying commitment: to ease suffering, support recovery, and restore a sense of control to people who may feel overwhelmed by illness or injury.

Rehabilitation services illustrate another side of healing: the work of restoring function and independence after injury or illness. Rehabilitation specialists and physical therapists translate medical recovery into practical, attainable movements. They design exercise programs that respect a patient’s goals—whether returning to work, enjoying a hobby, or simply moving with less pain. The therapeutic relationship matters here as much as the techniques; therapists listen for what daily life requires and tailor their plans to fit real routines. In this space, progress is measured not only in range of motion or strength but in a patient’s confidence that healing is possible and that the body can adapt to new realities. The horizon broadens when we consider the people who support recovery outside the clinic walls—the caregiver who reinforces exercises at home, the family member who celebrates small victories, and the community programs that keep patients engaged in meaningful activity.

Wellness and preventive care extend the reach of healing into everyday life. Personal trainers and fitness coaches help people build sustainable habits, translating medical advice into practical, enjoyable routines. Health educators work to demystify disease prevention, translate complex guidelines into accessible messages, and empower communities to take charge of their own health. The aim is not merely to treat illness but to reduce risk and build resilience before problems arise. This preventive work often operates where healthcare and social life meet—in community centers, schools, workplaces, and online spaces—where consistent guidance can alter life trajectories long before a symptom appears. The strength of these roles lies in their forward-looking emphasis: shaping environments and routines so that healthy choices feel possible, affordable, and socially supported.

Public health roles widen the lens beyond the individual patient to populations, recognizing that health is shaped by housing, nutrition, education, environment, and access to care. Public health nurses, for example, focus on disease prevention, vaccination outreach, and health education across diverse populations. Epidemiologists study patterns of disease to anticipate and interrupt outbreaks, guiding policies and resource allocation to where they will do the most good. These positions require a blend of scientific rigor and community-minded communication, because protecting health at scale demands both accurate analysis and trustworthy outreach. In this sense, helping people becomes a collective enterprise, one that depends on data-informed decisions and the courage to address disparities that show up in every neighborhood.

Support and management roles ensure that the systems of care function smoothly. Health administrators keep facilities running, integrate budgets with patient-centered priorities, and navigate the complexities of policy, staffing, and supply chains. Health informatics specialists harness technology to manage patient data, streamline workflows, and improve outcomes. These roles may feel more abstract than bedside care, but they are essential to delivering reliable, high-quality care. When a hospital operates efficiently, clinicians can focus more fully on patients; when information flows transparently, patients experience less confusion and greater trust. The modern healthcare landscape increasingly intertwines clinical expertise with digital capacity, and that blend expands what it means to help people. Telemedicine, remote monitoring, and data analytics open new pathways to support patients who might otherwise slip through gaps in care. In communities with geographic or transportation barriers, these innovations translate into real, lived access to care and timely intervention.

Amid these clinical and systemic aspects of care, the human element remains constant. The stories of resilience—like the public courage shown during emergencies—underscore the immediate, tangible impact of helping professions. The rescue efforts attributed to Xu Xinjian exemplify how urgent care and teamwork can avert tragedy. Equally powerful are the everyday acts: the clinician who notices a patient’s fear behind routine questions, the nurse who steadies a worried family member, the social worker who coordinates a safety net of services so a person can remain at home. These moments reveal that healthcare is not only about treating a diagnosis; it is about recognizing a person’s story, honoring their dignity, and supporting a path forward that honors their values and priorities. In many cases, the work extends into volunteer and community leadership—an illustration of how professional helping roles can radiate outward into broader social life. The Xiaolan example of volunteer coordination and community organizing echoes this truth: assisting health does not stop at the clinic door but continues in schools, boards, and neighbor networks where resources are mobilized and trust is built.

From a professional development perspective, the field offers diverse entry points and evolving trajectories. A direct-care worker may advance into supervisory roles or specialize in areas like palliative care, geriatrics, or pediatric home health. A nurse practitioner or physician assistant might explore subspecialties or expand into leadership positions that shape policy and care delivery at scale. Rehabilitation specialists may branch into specialized therapy areas or research that improves treatment protocols. Public health roles invite opportunities to design interventions that reduce inequities and measure impact at community levels. Health informatics and administration invite cross-disciplinary collaboration, blending clinical insight with technical and managerial skills. The path is rarely linear, but it is consistently oriented toward increasing the capacity to help. It is a profession that rewards curiosity, continuous learning, and a willingness to adapt as technologies, populations, and needs evolve.

This evolving landscape also highlights the importance of interprofessional collaboration. No clinician works in isolation; every patient benefit hinges on teams that communicate across disciplines, share knowledge, and coordinate care across settings. In such teams, the patient remains the center, and every member—whether they are providing direct care, enabling data flow, or addressing social determinants—contributes a vital piece of the healing mosaic. A culture of collaboration extends beyond the hospital walls to the communities those walls serve. It means listening to patients’ lived experiences, learning from them about what works in daily life, and adjusting care plans to fit realities rather than expectations. It also means acknowledging that health equity requires intentional outreach, culturally sensitive practice, and policies that ensure access to care regardless of income, location, or circumstance.

For readers charting a path through these possibilities, a reminder arises from the breadth and depth of healthcare professions: helping people through health is both a science and a humanities—the science of immunology, pharmacology, and physiology, and the humanities of empathy, patience, and trust. The practical steps—education, certification, hands-on experience, and mentorship—are complemented by a persistent commitment to improve communities. As digital tools reshape care delivery, there is also a renewed emphasis on preserving the human dimension of care. Technology should augment compassion, not replace it; data should illuminate needs, not obscure the person behind the chart. The balance is delicate but essential.

Within this frame, one can see how the broader theme of helping people extends beyond any single job title. It encompasses social workers guiding families through housing and safety concerns, teachers and educators extending learning to children and adults, counselors supporting mental health and career development, disaster relief workers coordinating rapid response, and legal aid attorneys advocating for justice when health decisions intersect with rights and resources. All these roles contribute to a more compassionate, resilient society. The healthcare professions described here sit at the heart of that ecosystem, sustaining health in the body and well-being in the community.

To connect these thoughts with the wider landscape of helping careers, consider how many paths begin with a simple, resolute choice: to be useful when others need it most. If you are exploring opportunities that align with a desire to make a meaningful difference, this chapter invites you to look at the continuum—from hands-on care to system-wide improvement—and to imagine how your talents might occupy a place within it. For a broader view of related pathways, you can explore a collection of careers designed to help people in diverse contexts: 17 Careers for Helping People.

As the field continues to grow, so too does the recognition of healthcare as both a profession and a public good. The resilience of communities depends on the steady presence of skilled workers who can respond to immediate needs and invest in preventive, sustainable health. This is not merely a career track; it is a commitment to seeing health as a shared responsibility, one that requires continual learning, collaboration, and unwavering care for the person at the center of every enterprise. The chapter that follows will expand on how other helping domains—social work, education, and advocacy—interweave with healthcare to form a comprehensive fabric of support. Together, these threads create a society more capable of recognizing need, responding with competence, and sustaining hope in difficult times.

External resources: For a broad overview of healthcare occupations and their outlooks, see the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics entry on healthcare occupations: BLS Healthcare Occupations Overview.

Weaving Neighbors into Networks: How Community Organization and Volunteerism Shape Careers That Help People

A steady thread runs through many of the jobs that aim to help others, a thread that sometimes stays hidden behind the more visible acts of care. That thread is community organization and volunteerism—the deliberate, sustained work of mobilizing people, resources, and ideas to address shared needs. When we speak of roles like social workers, teachers, nurses, or disaster responders, we are also speaking of ecosystems. These ecosystems rely on networks built by everyday citizens who show up, coordinate, and persist long enough to transform a neighborhood’s health, its learning opportunities, and its sense of safety. In this sense, helping people is not only about individual acts of kindness or specialized expertise; it is also about building durable systems that enable those acts to be timely, accessible, and just. The chapter that follows treats community organization and volunteerism not as a footnote to professional life but as a foundational practice that enlarges the horizon of what helping work can be and who can do it. It is a story about neighborhoods as laboratories of care, where people learn to lead, listen, and leverage their networks to meet real needs, from distributing essential supplies in a time of crisis to mentoring a child through a difficult school year, from coordinating a shelter response after a flood to advocating for policies that prevent harm in the first place.

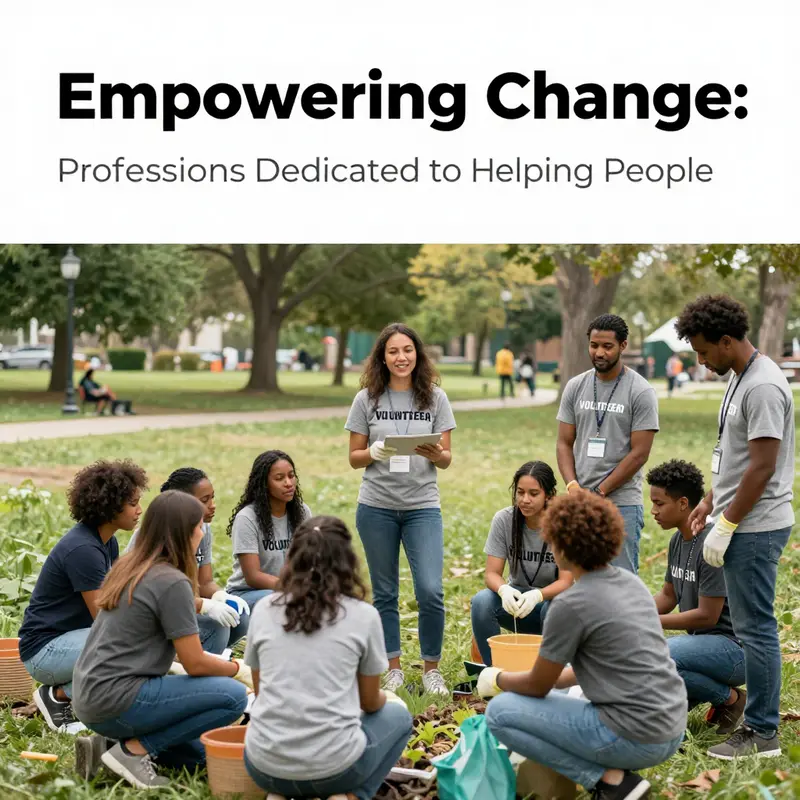

The power of organized volunteering lies in its ability to translate individual motivation into collective action. When a group of neighbors agrees to pull resources together, the energy grows beyond the sum of its parts. There is a natural chemistry in such collaborations: people discover strengths they did not know they possessed, and others discover roles that fit their skills and passions. The process creates trust, a currency more valuable than any single donation or grant. Trust becomes the glue that allows volunteers to work across differences in age, background, and experience, aligning them toward a common purpose. This is not mere sentiment; it is a practical capability. Strong volunteer networks reduce redundancy, fill gaps left by overburdened public services, and accelerate the delivery of help to those who need it most. They enable organizations to respond with flexibility to shifting conditions—whether a heatwave, a pandemic, or a sudden job loss in a community—and to sustain interventions long enough for real impact to take root.

Cultural contexts shape how these networks emerge and operate. In Japan, for instance, neighborhood associations have woven a centuries-old fabric of shared responsibility into daily life. These groups exemplify a long-standing tradition of neighbors helping neighbors, a social architecture that supplements government efforts rather than replacing them. The practice reflects a broader principle: meaningful help often grows from local knowledge, trusted relationships, and a willingness to share scarce resources in practical, visible ways. Volunteering in such settings is not simply about donating time; it is about integrating care into the rhythms of everyday life. This intimate scale—where a volunteer helps with a welfare program during weekend gatherings, or where residents coordinate a clean-up day to protect public health—demonstrates how community organization can be both intimate and expansive. It proves that the roots of professional helping work are often planted in voluntary soil, where early experiences of leadership, empathy, and service take hold and mature into formal careers later on.

From a practitioner’s viewpoint, the roles of volunteer coordinators and community organizers are crucial in turning benevolent intention into sustainable action. They exercise leadership not by commanding others but by clarifying needs, mapping capacities, and cultivating participation. They translate vague aspirations—reducing poverty, expanding educational access, protecting the vulnerable—into concrete projects with timelines, budgets, and evaluation. Their work touches many layers of society: schools, clinics, shelters, disaster-relief hubs, and cultural or faith-based organizations. They build teams that reflect the diversity of the communities they serve, recognizing that different perspectives strengthen problem-solving and broaden the range of solutions. Their skill set blends logistical acumen with interpersonal sensitivity: the ability to convene diverse stakeholders, to negotiate conflicting priorities, and to sustain momentum through the inevitable setbacks of ambitious social programs. The result is not merely a one-off distribution of goods or a temporary volunteer drive; it is the cultivation of social capital—the networks, norms, and mutual expectations that enable communities to weather storms and to grow stronger in the aftermath.

This ecosystem also serves as a powerful training ground for individuals seeking to enter helping professions. Volunteering offers authentic exposure to the challenges people face and the constraints institutions operate under. It provides a platform to practice listening deeply, communicating clearly, and solving problems under resource constraints. The experience of coordinating a neighborhood food drive, organizing a tutoring circle, or facilitating a peer-support group can illuminate the day-to-day realities behind policy statements or professional theories. For many, these experiences reveal a vocational calling or sharpen a sense of purpose that informs later career decisions in social work, education, healthcare, nonprofit management, or public health. The value is twofold: volunteers gain practical skills and confidence; organizations gain energy, new ideas, and a broader pool of potential staff or board members who already understand the community they aim to serve.

Within this framework, volunteerism often serves as a bridge to paid roles that center helping others. The pathway can begin with small, local acts but expand into leadership opportunities that shape organizations themselves. A volunteer coordinator might evolve into a program manager, learning how to secure resources, measure outcomes, and advocate for policy changes that expand access to services. A tutor who sees a child’s spark at the end of a tutoring session may become a mentor, a teacher, or a program designer who builds scalable educational interventions. The experiences of mentoring, organizing, and problem-solving become transferable assets that enrich resume narratives and deepen professional competence. In this sense, volunteering is not a separate track from paid work; it is a fertile ground where compassion and capability are cultivated in tandem, ready to flourish into responsible, impactful careers.

To make this progression tangible, consider a few archetypes that recur in community-driven help work. A social worker who begins with neighborhood outreach often learns the realities of poverty and mental health by listening directly to those affected, then translates those insights into resource connections and counseling pathways. A disaster-relief volunteer who learns to triage needs under pressure may later manage a nonprofit program that coordinates long-term housing or recovery services. A mentor who helps a disengaged student find study habits and confidence can evolve into a program director who designs learning supports for under-resourced schools. Each arc demonstrates how volunteer experiences seed professional development, creating a lineage that connects intimate, local act to broad, systemic impact.

Crucially, the value of organized volunteerism extends beyond individual gains. It strengthens the very fabric of civil society. When communities mobilize, they demonstrate that care is a collective enterprise, not an optional add-on. The practice builds civic trust, fosters accountability, and invites broad participation in decision-making. It creates spaces where people from different backgrounds can collaborate on shared purposes, an environment in which empathy grows into action and action grows into institutions. This is the sense in which community organization is foundational to the broader enterprise of helping—because it teaches how to translate concern into coordination, and coordination into sustainable care. In such settings, policy and practice begin to reinforce one another: volunteers identify gaps, communities advocate for change, and public services adapt to meet evolving needs. This reciprocal dynamic is a powerful reminder that the most effective help comes from networks that are as resilient as they are responsive.

The chapter would be remiss without acknowledging the ethical and cultural considerations that govern volunteer work. Freedom to associate and participate in community life—concepts explored in scholarly examinations of civic engagement—underpin the legitimacy and vitality of volunteer-driven efforts. When people can organize around common aims without fear of reprisal, they are more likely to bring diverse perspectives into problem-solving, challenge inequities, and sustain long-term commitments even when immediate donations wane. This collective liberty is not a fringe benefit; it is the condition that allows volunteers to test ideas, celebrate successes, and adapt when things do not go as planned. From a practical standpoint, it means providing trainings that emphasize consent, cultural sensitivity, and inclusive leadership. It means listening to those who are most affected by the issues at hand and ensuring that their voices guide the design and evaluation of programs.

For readers who want a clearer sense of how these pathways translate into real career opportunities, consider exploring the broader landscape of helping professions. A resource that maps a wide range of roles—drawing on experiences in social work, education, health care, disaster response, nonprofit management, and community organizing—can illuminate how volunteering can evolve into formal employment or leadership. One such entry point highlights a spectrum of possibilities that begin with service and lead to professional roles that sustain long-term impact: 17-careers-for-helping-people.

As this exploration circles back to the central premise of the article, it becomes evident that the work of helping people is inseparable from the work of building and sustaining communities. The volunteer who coordinates a neighborhood nutrition program or the neighbor who participates in a once-a-month cleanup are not just performing acts of charity; they are investing in social infrastructure that supports health, education, and safety for the long haul. These efforts create pathways for others to participate, learn, and grow, reinforcing the notion that care is both a practice and a policy. When communities organize well, they enable professionals to do their jobs more effectively and humanely. When professionals respect and collaborate with volunteers, they expand the reach and relevance of their services. The synergy is real, and its effects ripple outward—from individual resilience to school achievement to public health outcomes. The result is a more compassionate, more capable society, one in which helping people becomes a shared venture, not a solitary calling.

External resources can enrich this understanding and offer broader context on how voluntary associations shape social life. For a deeper theoretical lens on how community organizations empower people and influence civic life, see Freedom of Association on ScienceDirect. Freedom of Association.

Internal link: readers seeking concrete career pathways tied to these experiences may find value in reviewing approaches and opportunities described in the resource that compiles diverse roles focused on helping people, including how volunteering can transition into professional tracks. For a concise overview of potential career trajectories, explore the article 17-careers-for-helping-people.

Together, these perspectives remind us that the jobs to do with helping people begin long before a title appears on a resume. They begin in the everyday acts of showing up, offering a listening ear, and organizing people around a shared purpose. They begin in the quiet confidence that communities can become stronger when neighbors step forward with intention and care. And they continue as individuals discover new ways to turn that care into lasting, meaningful work that serves others today and builds the capacity to help tomorrow.

Counseling as a Lifeline: Navigating Personal Growth and Career Guidance in the Helping-People Landscape

Counseling as a career is more than one profession among many. It is a lifeline that connects people to their own capacity to endure, adapt, and grow. The work rests on listening, yes, but it is built on structure, technique, and a steady practice of evidence-based approaches. Counselors help clients face pain, confusion, and change with clarity and dignity. They guide, they reflect, and they co-create plans that make life more workable. This is not just talk; it is a collaborative process that translates fear or uncertainty into steps, milestones, and meaningful progress. In this way, counseling stands as a pillar within the broader family of helping roles, one that blends science with humanity to support real-world outcomes.

The field is richly varied, embracing multiple specializations that reach different populations and settings. Mental health counselors work in clinics, hospitals, and community centers. They support children and adolescents, adults, and elders dealing with anxiety, depression, trauma, and addiction. LGBTQ+ individuals may find affirming space in these services, while families navigate dynamics that affect daily life. School counselors operate where learning and development meet personal growth, guiding students through academic challenges, social pressures, and planning for the future. In the realm of work, career counselors focus on helping people understand themselves and translate that understanding into education, training, and employment choices. Across outpatient clinics, emergency departments, private practices, and nonprofit organizations, the core practice remains the same: listen deeply, speak honestly, and partner for action. Telehealth has expanded reach in recent years, delivering support to rural areas, urban clinics, and anywhere in between. The variation in settings underscores a simple truth: helping people is not confined to a single room or a single method. It is a dynamic practice that adapts to context while maintaining a steady commitment to client well-being.

A central distinction within the field is the role of career counseling. It sits alongside traditional mental health work but emphasizes a developmental horizon. Career counselors help people understand who they are—values, strengths, interests—and what they want to become in education and work. This is not a one-off coaching moment; it is a developmental journey that unfolds over time. The process begins with self-knowledge, often gathered through interviews, inventories, and reflective exercises. From there, counselors help clients translate those insights into concrete plans: choosing majors or certificates, identifying transferable skills, pursuing internships, and building networks. They also illuminate the labor market—what kinds of roles exist, what skills are in demand, and how to prepare for them. This broader lens helps clients navigate uncertainty with a roadmap rather than a guess, which can be especially powerful after a major life transition, such as entering the workforce after school or shifting careers mid-life.

The demand for skilled counselors is rising for several reasons. Increased awareness of mental health issues has reduced stigma and opened doors for legitimate help. People recognize that emotional and career well-being are intertwined with overall functioning. The modern economy, with its rapid changes and shifting requirements, heightens the need for personalized support rather than generic advice. Counselors are increasingly involved beyond one-on-one sessions. They contribute to research, shape program design, and participate in policy discussions that address access and quality of care. Some pursue roles in higher education, teaching the next generation of practitioners; others explore research that informs best practices across communities. There is room for innovation, too. Counselors can contribute to community outreach, development of school-based mental health programs, and workplace initiatives that foster growth and resilience. The field rewards lifelong learning, curiosity, and the discipline to apply evidence to diverse client needs.

Training and ethical practice form the backbone of effective counseling. Most paths blend solid theoretical foundations with practical experience. Students engage with core theories in psychology and counseling, then bring those ideas to life through supervised internships and clinical practica. Licensure or credentialing is common for clinical and some school-based roles, providing a guardrail that protects clients and maintains professional standards. Even when a formal license is not required, ongoing professional development remains essential. Clinicians stay current with research on trauma, neurodiversity, cultural responsiveness, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Supervision and peer consultation are not afterthoughts; they are essential mechanisms for reflection, accountability, and growth. They help practitioners recognize blind spots, test new approaches, and ensure that care remains person-centered and evidence-informed. In this light, counseling is a practice of continuous improvement, anchored in ethics, confidentiality, and respect for every client’s dignity.

The impact of counseling becomes most visible in moments when a client feels truly heard and empowered to act. A child who learns to regulate emotions gains a tool for daily life. A student who discovers a clear pathway through a maze of courses experiences relief and motivation. A worker who negotiates a more meaningful role finds confidence and purpose returning to work. Career counseling can translate complex markets into navigable steps. It helps clients articulate their values, assess skills, explore possibilities, and pursue opportunities with a concrete plan. The counselor’s toolkit—interviews, inventories, reflective exercises, and goal-setting frameworks—supports autonomy. The aim is not dependency but empowerment. Resilience grows as clients learn to cope with setbacks, adapt to new contexts, and maintain momentum toward their goals.

Yet every path of service carries challenges that demand resilience and imagination. Access barriers persist, particularly for people in underserved communities. Cost, geography, and stigma can delay or deter help-seeking. Cultural sensitivity is a fundamental competency, not an add-on. Counselors must attune to diverse family structures, belief systems, and communication styles while acknowledging systemic barriers to education and employment. Ethical practice requires clarity about confidentiality, boundaries, and risk assessment. Ongoing supervision, mentoring, and peer support help keep practice aligned with values and evidence. The field also asks practitioners to balance warmth with professional boundaries, empathy with accountability, and hopeful ambition with realistic timelines. When navigated thoughtfully, these tensions deepen trust and expand the reach of help.

Counseling thrives when it collaborates with other helping professions. Social workers address housing, safety, and basic needs; teachers and school staff support learning and social development; nurses and clinicians manage health concerns; community organizers mobilize resources for marginalized groups. Multidisciplinary teamwork creates a seamless web of support that improves accessibility and outcomes. In schools, counselors coordinate with teachers, administrators, parents, and community partners to foster environments where learning and well-being can flourish. In workplace settings, career counselors can partner with human resources and leaders to craft clearer career pathways, offer targeted training, and ease transitions that reduce burnout. The shared aim across these roles is to weave support into everyday life, so people can pursue growth with fewer barriers and more confidence.

To place counseling within the broader spectrum of helping professions, it helps to remember that the field offers many entry points and trajectories. If you are drawn to listening, reflection, and strategic planning, counseling provides a sturdy foundation across contexts—from mental health support to educational guidance, from private practice to policy-oriented roles. For readers exploring the pathways that lead to such work, one guide highlights the diversity of helping careers. It reinforces the idea that the impulse to help can unfold through multiple channels, and that counseling remains a powerful, scalable way to translate that impulse into lasting outcomes. For an overview that frames these possibilities, see the resource: 17-careers-for-helping-people.

The journey of becoming a counselor is not only about secure work or a clear title. It is about cultivating a professional identity that blends science with empathy, practice with reflection, and care with accountability. It invites continuous learning, supervision, and collaboration. It invites professionals to hold space for clients while also challenging them to grow. For those who want to make a durable difference—through crisis moments and through ordinary days—counseling offers a path that honors individuality while building shared resilience. It is a career that grows with the person being helped, recognizing that every client’s journey is unique and that every supportive conversation can seed a healthier future. The chapter on counseling as a career path thus threads through the article’s overarching purpose: to illuminate how many dedicated roles contribute to a more compassionate, resilient society.

For a broader understanding of counseling careers and licensure pathways, see the American Counseling Association’s Careers in Counseling resource: American Counseling Association – Careers in Counseling.

Final thoughts

The professions that revolve around helping others come in many forms, each playing an essential role in cultivating a healthier, more informed, and supportive society. Business owners have the unique opportunity to engage with these fields through partnerships, support, or corporate giving, amplifying the positive effects of these roles in the community. By recognizing and advocating for the value of these professions, business leaders not only enhance their corporate image but also contribute to a collective effort to uplift and empower individuals and families in need.