Occupational therapy tools represent crucial resources in helping individuals regain their independence after injury, illness, or disability. These specialized devices are not only vital for rehabilitation but are also key to enhancing patients’ quality of life as they recover. The tools play a significant role, especially in restoring hand function, integrating technology, and facilitating daily activities. From traditional exercises to the latest in virtual reality, occupational therapy tools offer dynamic solutions to meet diverse patient needs. Each chapter of this article delves into specific tools and innovations, examining their impact on rehabilitation, independence, and overall patient engagement.

Hands in Motion: Weaving Tools, Technology, and Daily Function in Hand-Function Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation of hand function sits at a pivotal crossroad in occupational therapy. It is where the clinic meets daily life, where the precision of science meets the resilience of everyday practice, and where tools become more than equipment—they become partners in restoring independence. The hand is small in size but vast in its reach, enabling our clients to grip a cup, button a shirt, or sign a name. When injury, illness, or disability alters these capabilities, the sequence of recovery is often anchored by the thoughtful selection and orchestration of tools designed to rebuild strength, dexterity, coordination, and confidence. In practice, therapists tailor a continuum of interventions to the person’s stage of recovery, the specific joints and movements affected, and the functional goals that matter most to the client. The result is a cohesive tapestry of devices and technologies that supports both structured clinical sessions and meaningful, independent practice at home.

A central thread in this tapestry is the hand therapy table, a versatile apparatus that has become indispensable in the middle to late stages of rehabilitation. Its design centers on modularity and progression. A single table can offer multiple movement training modules and several independent resistance levels, targeting fingers and wrists with increasing specificity. Practically, therapists use the table to guide patients through sequences that build joint mobility, muscle strength, endurance, flexibility, and fine motor control. The beauty of this approach lies in its adaptability: the same device can be scaled for someone emerging from an acute phase who needs gentle, controlled motion, or for a person at a more advanced stage who is practicing complex coordination tasks. In group settings, the table becomes a social, motivating platform—four clients can train side by side while a therapist observes patterns of grip, release, and tremor, offering feedback that fosters better motor control and proprioceptive awareness. The table’s capacity to provide real-time, adjustable resistance supports a systematic approach to therapy, one that mirrors the varying resistance the hand encounters in daily life—from gripping a water bottle to manipulating a zipper or turning a key. This kind of progression is more than physical; it reinforces the patient’s belief in possibility as movements become smoother and more automatic.

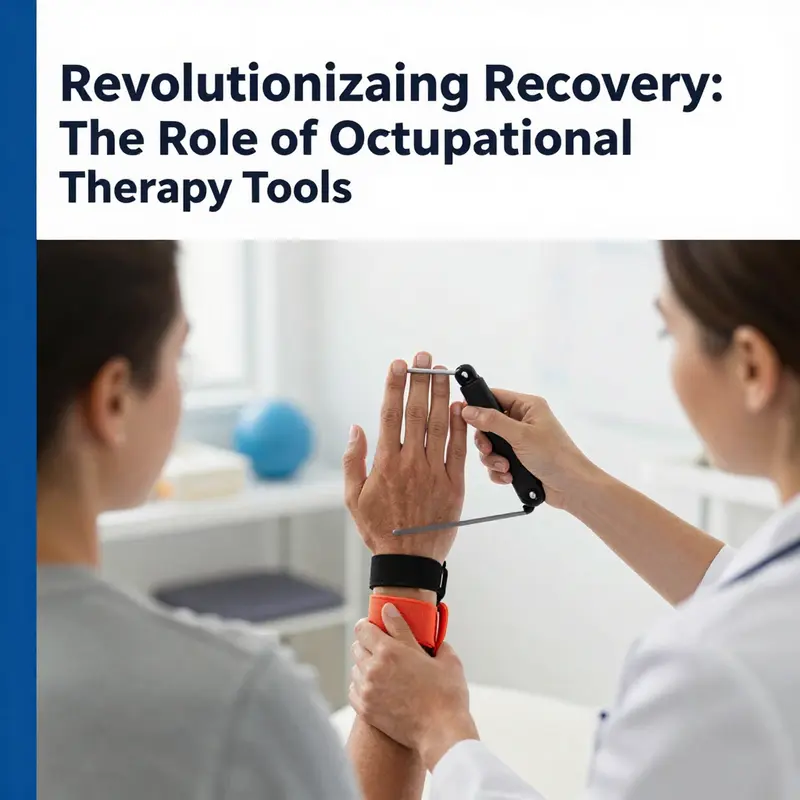

Alongside broader, table-based training, therapists increasingly integrate devices that add resistance and specificity to finger tasks while preserving simplicity and durability. A screw-wood finger rehabilitation device illustrates this principle well. Constructed from natural wood and reinforced with metal bolts, such devices offer a robust, adjustable means to challenge grip, pinch, and coordination. The rows of holes and the threaded bolts invite therapists to calibrate the level of resistance to align with a patient’s current strength and recovery trajectory. The appeal of this class of tools lies in their tactile feedback and predictability; each session becomes a precise calibration of effort and outcome. While this kind of device is often used in clinical settings, its design supports consistent use across settings—from therapy rooms to home exercise programs—provided safety and hygiene standards are observed. For patients, the gradual increase in resistance can translate into meaningful gains in functional tasks, such as manipulating small objects, opening containers, or assembling simple components of daily routines. The emphasis remains squarely on function: every squeeze or twist is a rehearsal of the real-world actions that the client will perform without assistance.

To complement these more structured modalities, portable therapy kits offer a practical bridge between clinic and home. These compact collections typically include grip strength trainers, finger strengtheners, and small exercise balls, all intended to facilitate targeted hand exercises with minimal equipment. Portable kits are particularly valuable for chronic conditions like arthritis, where maintaining strength and dexterity requires consistent, low-impact activity. The portability reduces barriers to practice, enabling clients to embed therapeutic activity into everyday moments—waiting for a ride, sitting during a commute, or taking a short break at work. When used under the guidance of a clinician, these kits support a steady cadence of practice, reinforce correct movement patterns, and help monitor progress over weeks and months. The shift toward home-based practice is a cornerstone of contemporary hand rehabilitation, reflecting a restorative vision in which therapy continues beyond the clinic walls and into the rhythm of daily life. In this sense, the tools become extensions of the therapist’s plan, translating clinical goals into observable, repeatable actions that patients can steward themselves.

Beyond mechanical devices, the integration of technology marks a transformative expansion in how hand rehabilitation is conceived and delivered. Wearable sensors and immersive systems are not ends in themselves but accelerators of motor learning. A wearable armband that detects muscle activity and translates signals into digital commands represents a bridge between biological signals and interactive tasks. Such systems can translate subtle muscle activations into computer or device control, offering an avenue for neurorehabilitation that is both engaging and informative. The allure is twofold: first, patients experience the immediacy of feedback as they attempt precise finger and wrist movements; second, therapists gain quantitative insight into motor capacity, enabling more accurate progression and remote monitoring. The clinical value lies in the careful integration of these technologies with traditional practice—ensuring that they reinforce functional tasks rather than simply delivering novelty. When paired with patient-centered goals, wearable technology supports endurance-building activities, promotes repetition, and sustains motivation through interactive feedback loops.

Another powerful frontier is the incorporation of immersive, gamified therapy systems, blending augmented reality or virtual reality with therapeutic movements. In these systems, functional tasks such as reaching, grasping, and manipulating objects are embedded in engaging environments that reward repetition and accuracy. Research comparing VR-based interventions with conventional therapy has highlighted improvements in motor function and patient engagement, underscoring the potential for technology to amplify recovery while sustaining interest over time. For clinicians, the challenge is to harness the motivational advantages of gamification without losing sight of the functional relevance of every movement. The clinician’s task is to tailor virtual tasks to real-world activities—like picking up a cup, buttoning a shirt, or turning a doorknob—so that skills acquired in a virtual space readily translate to independence in daily life.

In embracing these tools, occupational therapists emphasize user-centered design. The most effective devices are not merely technically sophisticated; they are intuitive, comfortable, durable, and adaptable to the client’s home environment. A key aspect of successful tool use is aligning practice with practical routines—meal times, dressing, or personal care—so that therapy becomes a natural extension of living rather than an extra obligation. This requires ongoing communication with clients and their caregivers, as well as thoughtful consideration of cognitive demands, sensory preferences, and safety considerations. For example, while a high-tech VR setup can be deeply engaging, it is essential to ensure that the tasks are accessible for someone with limited vision or difficulty with sequencing. In such cases, therapists may pair immersive experiences with more conventional, hands-on tasks to preserve motivation while ensuring progressive challenge. The overarching aim is to build a coherent, enjoyable, and sustainable rehabilitation journey—one that respects the client’s pace, preferences, and living context.

To maintain coherence across this spectrum of tools, clinicians often consult a broad array of resources, including reference materials and professional practice guidelines that emphasize functional outcomes, safety, and user experience. An important practical consideration is the availability and accessibility of tools for home use. Therapists collaborate with clients to establish a regimen that fits daily life,-balancing devices that require supervision with those that can be safely used independently. In doing so, practitioners support not only physical recovery but also psychological resilience—the sense that recovery is within reach, that effort translates into tangible gains, and that daily routines can reflect a renewed sense of competence.

As this chapter threads together the various tools—table-based modules, adjustable finger devices, portable kits, wearable sensors, and immersive technologies—it becomes clear that the strength of hand function rehabilitation lies in integration. The devices and systems, while diverse, share a common purpose: to enable people to perform core ADLs with confidence and to participate more fully in the roles they cherish. The chapter’s examples illustrate a continuum from basic strengthening to sophisticated sensor-driven learning, but the heart of rehabilitation remains the same: meaningful activity, repetition, feedback, and incremental challenge that respects the person’s dignity and autonomy. For students and practitioners alike, recognizing how to mix and match these tools within a client’s unique story is the essence of effective occupational therapy.

For readers seeking practical pointers on equipment and setup, consider exploring resources that discuss the wide range of tools and equipment used by occupational therapists. A dedicated overview can offer guidance on selecting appropriate devices, setting up home exercises, and ensuring safety and accessibility in daily life. Internal link: Tools and Equipment for Occupational Therapists. This resource provides a comprehensive starting point for understanding how the arsenal described above translates into real-world practice and supports therapists in crafting individualized, sustainable rehabilitation plans.

External resource for further reading on technology-enhanced rehabilitation and its applications in hand therapy can be found in the neuroscience and rehabilitation literature. For researchers and clinicians interested in the evidence base behind immersive and sensor-driven approaches, an external study in a leading neurorehabilitation journal offers insights into how virtual and augmented reality can augment traditional therapy while sustaining patient engagement. External resource: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00165/full

In sum, tools in occupational therapy for hand function rehabilitation are more than devices; they are pathways back to everyday life. When selected thoughtfully and used with patient-centered intent, they enable a resilient recovery—one that is measured not only by improved grip strength or finer motor control but by restored participation in the daily activities that define independence and well-being.

Rewriting Rehabilitation: The Transformative Potential of Virtual Reality in Occupational Therapy

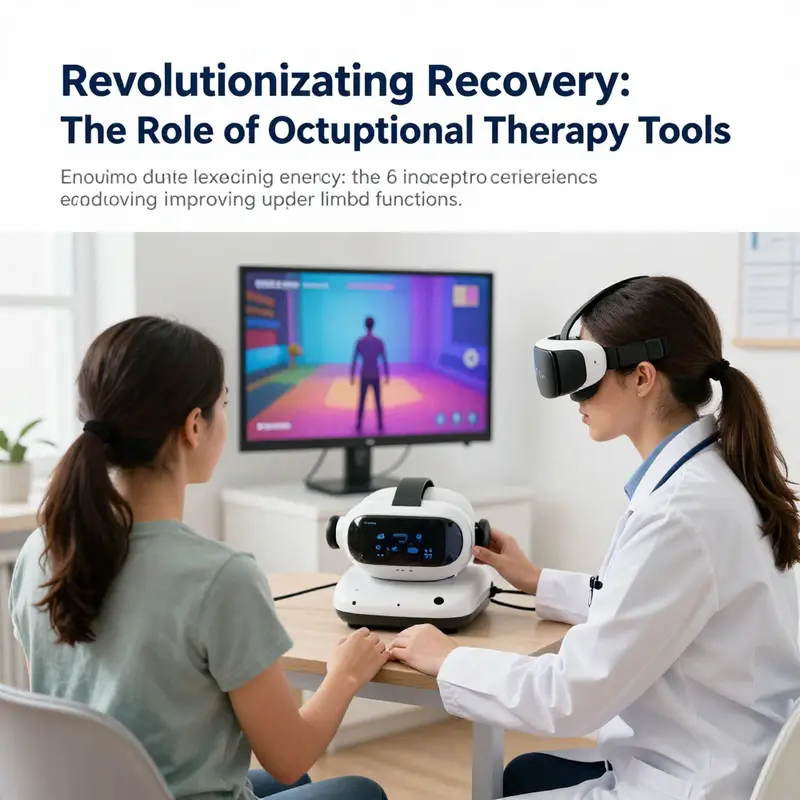

Virtual reality has moved beyond entertainment to become a structured modality within occupational therapy. In clinics and increasingly in patients’ homes, VR platforms offer immersive environments that strip away the monotony of repetition while preserving the essential repetition that drives neuroplastic change. The technology is not an end in itself but a scaffold that supports meaningful task practice. For individuals recovering from neurological injuries or spinal cord impairment, the ability to practice reaching, grasping, manipulating objects, and coordinating fine motor actions within varied contexts is central to regaining independence in daily life. VR can simulate kitchen tasks, dressing activities, or household chores with adjustable difficulty, sensory feedback, and real-time performance data. This capability aligns with the core aim of occupational therapy: to enable people to participate in activities that matter to them, with safety, efficiency, and confidence. The challenge has always been to translate clinical exercises into activities that feel purposeful, motivating, and emotionally engaging. VR helps bridge that gap by transforming repetitive drills into adventures that still honor the science of motor relearning.

Recent research has begun to illuminate how VR translates into tangible gains. In a study focusing on spinal cord injury rehabilitation, ten male participants with injuries ranging from cervical level C5 to lumbar L2 engaged in VR-based therapy as part of acute care. The authors observed a striking increase in both effort and willingness to push beyond perceived physical limits during VR sessions. Participants reported that the tasks felt challenging yet attainable, and this sense of progress fostered persistence when conventional therapy had plateaued. Importantly, the interventions were described as safe and comfortable; no additional pain or discomfort emerged during training, and therapists noted that the activities did not impose undue strain on the musculoskeletal system. The accessibility of the system also emerged as a strength: individuals with little prior experience with computer technology could navigate the programs independently. This is not about technical prowess; it is about confidence in movement, the belief that the body can respond to practice, and the sense that therapy is controllable rather than imposed. In such a setting, motivation becomes a measurable therapy outcome, not merely a side effect.

Within the same study, a comparison of two VR platforms—console-based and PC-based games—revealed similar functional capabilities and user-friendliness. The parallel performance of both platforms suggested that clinicians can choose based on practical considerations rather than inherent superiority. Yet several pragmatic differences emerged that have real-world implications. PC-based configurations were noted for greater portability and simpler setup, features that matter in busy clinical environments where space is at a premium and staff must deploy interventions quickly between patients. In practice, this means therapy teams can move VR equipment between rooms or bring it into patients’ rooms for bedside practice, a flexibility that supports continuity of care and reduces scheduling friction. For some patients, home use appears feasible as well, given adequate supervision and clear safety protocols. The looser constraints of PC systems also allow more naturalistic interfaces and richer data capture, enabling therapists to monitor progress over time with objective metrics such as movement quality, speed, and range of motion. While console-based VR remains valuable, PC-based systems offer a practical pathway to broad adoption in clinics and homes alike.

These findings invite a broader reexamination of how occupational therapists design and sequence rehabilitation. VR is not a replacement for traditional therapy but a powerful complement that can transform routine tasks into purposeful, goal-oriented activities. When a patient practices reaching for a cup, turning a door handle, or arranging objects on a shelf within a simulated but meaningful context, the session resembles real life more closely than repetitive isometric drills. Therapists can calibrate difficulty, adjust speed, and introduce multisensory feedback that reinforces correct movement patterns. The data streams produced by VR—timing, trajectory, grip force, error rates—offer practitioners objective insight into progress, fatigue levels, and learning plateaus. This information can guide decisions about pacing, rest breaks, and the introduction of new tasks. It also supports shared decision-making with patients, who can observe their improvements in visual dashboards and feel a sense of mastery that extends beyond the clinic walls. The result is therapy that respects the individuality of each client, aligns with their daily routines, and sustains motivation over weeks and months of rehabilitation.

Beyond the immediate mechanics of movement, VR embodies a broader shift toward technology-driven, user-centered design in occupational therapy. The most compelling VR systems integrate seamless motion tracking with intuitive controls, safety safeguards, and engaging narratives that reflect users’ values and preferences. They invite patients to participate in tasks that look and feel like real life, not sanitized exercises. For therapists, this means a toolkit that scales with an individual’s progress and a platform that can be tailored to diverse populations, from older adults with limited mobility to younger patients pursuing meaningful functional goals. The accessibility observed in the SCI cohort signals that age and prior tech exposure are less of a barrier when interfaces are designed with clarity and forgiving feedback. At the same time, clinicians must remain attuned to potential risks, such as cybersickness, fatigue, or cognitive overload, and implement screening, training, and breaks as part of standard practice. Integrating VR with other assistive technologies, such as wearable sensors or adaptive input devices, can enrich the therapeutic experience while preserving safety and comfort. In short, the value of VR lies not in novelty, but in its capacity to mediate repeated, purposeful practice in a way that feels meaningful to each person.

Within the evolving dialogue about technology in occupational therapy, questions about how these tools integrate with broader care plans are essential. As technology becomes more central, clinicians, researchers, and educators discuss strategies for aligning virtual reality practice with established therapeutic goals and environmental adaptations. For readers seeking deeper context, conversations about technology’s role in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy illuminate how digital modalities can support mental health, independence, and daily functioning across settings. See the discussion on how technology informs patient care in occupational therapy for broader framing. technology’s role in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy. This link anchors the chapter in a practical discourse about integrating tech-enabled approaches within standard clinical pathways and school or community programs alike.

Looking ahead, the potential of VR in occupational therapy is neither speculative nor confined to laboratory settings. It is already informing how therapists set goals, track progress, and shape daily activities that matter to patients. The capacity to bring high-engagement practice into clinical routines can shorten the path to independence, reduce frustration, and widen access to meaningful rehabilitation, particularly for people with complex needs where conventional therapy may feel repetitive or stilted. Yet the technology remains a tool that requires thoughtful integration. Clinicians need training, patients require orientation, and care teams must ensure that VR tasks mirror real-life demands while respecting safety limits. The reform is not about substituting clinical judgment but about expanding it with data-rich practice environments. In time, home-based VR programs may become standard complements to clinic sessions, with therapists guiding remote sessions, monitoring outcomes, and adjusting plans as recovery unfolds. For those seeking a broad synthesis of VR’s OT impact, the systematic review in PubMed Central offers extensive context. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10793456/

This ongoing work will help determine which settings, patient groups, and task types benefit most, guiding policy and training as VR becomes a standard component of care.

Grasping Independence: Designing Adaptive Utensils as a Keystone of the Occupational Therapy Tool Kit

Mealtime is more than nourishment; it is a daily ritual that sustains autonomy, social connection, and self-respect. For many individuals recovering from neurological injuries or living with chronic motor limitations, the act of feeding can become a measure of independence. Adaptive utensils sit at the heart of occupational therapy tools because they translate intention into action. They are quiet, practical interventions that reduce effort, compensate for weakness or tremor, and encourage a sense of mastery during a moment that is essential to daily life. The value of these tools lies not only in their mechanical design but in how they fit a person’s routine, body, and goals. In a clinical world increasingly attuned to patient-centered care, adaptive utensils exemplify how a seemingly simple device can ripple outward, improving nutrition, mood, and participation in everyday conversations around the dining table.

At their core, adaptive utensils modify the basic act of scooping or guiding a bite into the mouth. The design priorities are straightforward yet powerful: lessen the energy cost of eating, stabilize the hand and wrist during the motion, and position the food closer to the mouth to minimize awkward reaching. The features—shape modification, weight adjustments, angled configurations, and enhanced grips—work in concert to support diverse needs. Shape modification often means a thicker, more ergonomic handle that distributes pressure across the palm rather than concentrating it at a small, sore spot. This simple alteration can transform a shaky grasp into a secure hold, enabling controlled movements rather than repeated slips. Weight adjustment introduces a counterbalance that can calm tremors and steady micro-motions, a principle grounded in motor control research. A slightly heavier utensil may sound counterintuitive, yet for many individuals, the extra mass provides inertial stability that makes precise hand-to-mouth transitions more reliable.

The angled design is particularly thoughtful for those with limited shoulder or neck range. By tilting the bowl or spoon toward the mouth, the user maintains a near-vertical trajectory for the hand, reducing the need for forward reach and awkward wrist extension. This orientation can minimize compensatory postures in the trunk and shoulder, which, over time, may reduce fatigue and discomfort. Grip enhancements, whether through built-up handles, textured surfaces, or contoured molds, accommodate individuals with arthritis, weak pinch strength, or sensory sensitivities. The aim is not to force a specific grip but to offer a spectrum of options that respect how a person currently holds objects while gently guiding the hand into more efficient patterns of movement.

These design considerations emerge from careful assessment within occupational therapy practice. A clinician begins by observing how a patient grasps and lifts utensils in a standard meal setup, noting where slipping, heavy forearm fatigue, or misalignment occur. They then translate those observations into a tailored combination of features. The choice of material also matters: surfaces that are easy to clean, resistant to moisture, and safe for food contact support long-term use without creating new hazards. A utensil that feels comfortable in the hand but is difficult to sanitize or inherits a rough surface will undermine its therapeutic value. Cleanliness and safety, therefore, join comfort and function as essential criteria in the design process.

Beyond the mechanics, adaptive utensils carry profound psychological and social implications. When a person can feed themselves without assistance, the act reverberates through identity and dignity. Mealtimes shift from being moments of dependence to occasions of participation. This shift often deepens engagement with family and peers, inviting conversation and shared rituals that reinforce motivation for ongoing therapy. In pediatric settings, utensils that support the development of fine motor skills through play or practical tasks become tools for family-centered care. Children learn by doing, and even small improvements in control or speed can build confidence, encourage exploration of food textures, and reduce anxiety around new foods or social dining situations. The caregiver’s experience also improves as the load of daily tasks lightens; caregivers gain time and emotional bandwidth to foster development in other areas, creating a more holistic recovery environment.

The social ecology surrounding mealtime also matters. A well-fitted utensil set can accommodate a range of dining contexts, from home kitchens to school cafeterias, enabling consistent participation across environments. When a device feels reliable and unobtrusive, a person is more likely to practice. Repetition is a central component of neural recovery and skill maintenance, and adaptive utensils can support the repeated, meaningful practice needed to transfer motor gains from therapy sessions to daily life. The integration of these tools into routine activities underscores a fundamental principle of occupational therapy: tools should enable meaningful occupation, not simply perform a task.

In practice, adaptive utensils must be adaptable. Hand injuries and degenerative conditions are rarely uniform, so a one-size-fits-all approach would limit their usefulness. Clinicians often tailor utensils along several dimensions—handle diameter, weight range, angle of the bowl, and the texture of the gripping surface—so that the device aligns with the user’s anthropometry and comfort level. For some, a lighter utensil with a broader, smoother grip reduces fatigue; for others, a weighted option may be essential to control tremor and stabilize resonance of movement. The sequence of adjustments is patient-specific. It may begin with a thicker grip to support a weak grasp and progress to an angled bowl that reduces neck strain as meals become more automated. This iterative process illustrates the core OT principle of customizing tools to support a person’s unique function, environment, and goals.

An often overlooked but critical aspect is maintenance and independence in care. utensils must withstand daily use and be simple to clean. The most elegant design can lose its therapeutic value if it requires delicate handling or specialized cleaning procedures that a user cannot easily perform at home. Therefore, designers and clinicians emphasize durability, ease of disassembly for cleaning, and compatibility with common household dishwashers. Color and texture choices, while seemingly incidental, can influence user acceptance. High-contrast handles may assist individuals with reduced visual acuity, and tactile textures can help users with sensory processing differences distinguish between utensils at a glance and feel. This attention to sensory and perceptual detail reflects a broader commitment in occupational therapy to create devices that respect varied sensory experiences while promoting consistent use.

The pediatric dimension adds another layer of complexity and opportunity. For children, adaptive utensils can support fine motor development while engaging the imagination. When a utensil feels like a friendly tool rather than a clinical device, a child is more likely to explore mealtime with curiosity, experiment with different grips, and gradually refine control. Family education becomes essential here: caregivers learn how to introduce adjustments, when to switch between grip sizes, and how to pair utensil use with enjoyable mealtime routines rather than turning therapy into a rigid ritual. In all cases, the aim remains constant—maximize independence while supporting safety and enjoyment at the table.

In keeping with contemporary approaches to rehabilitation, this chapter also speaks to the importance of user-centered design. Adaptive utensils are not merely about enabling function; they are about empowering choice. A well-designed utensil set offers a spectrum of options that respect the user’s preferences for weight, angle, and grip feel. It invites experimentation and gradual progression toward more efficient movement patterns. This philosophy aligns with broader trends in occupational therapy that emphasize collaboration, feedback, and iterative refinement. Clinicians often involve patients in the selection process, providing demonstrations of how subtle changes in handle diameter or bowl angle translate into different movement experiences. In doing so, the therapy remains a partnership rather than a prescriptive intervention, reinforcing the patient’s agency within recovery.

The practical implications extend to the broader ecosystem of therapy tools. Adaptive utensils do not exist in isolation; they complement other assistive devices, positioning aids, and even environmental adaptations in the home. When a person can cut, scoop, or lift with greater ease, they are more likely to engage in a wider range of self-care activities, which can cascade into improved nutrition, better hydration, and a more varied diet. These improvements, in turn, support energy, mood, and participation in everyday life. Clinicians may weave adaptive utensils into a comprehensive plan that also includes dressing aids, adapted kitchenware, and safe meal setup strategies. The aim is to orchestrate a coherent suite of tools that work in harmony, enabling consistent practice and meaningful occupation across contexts.

For practitioners seeking practical guidance beyond theory, a wealth of resources exists that catalog the varieties of tools and equipment used in occupational therapy. One of the strengths of the field is its ability to connect practitioners with practical, evidence-informed options that can be tailored to each client’s living situation. When a therapist considers adaptive utensils, they weigh not only the functional gains but the ease with which a person can incorporate the tool into daily routines. This holistic stance helps ensure that gains in grip strength or control translate into real-world capability and confidence during meals, social gatherings, and everyday self-care.

As this discussion shows, adaptive utensils embody a core value of occupational therapy: the transformation of a small tool into a conduit for autonomy. They exemplify how thoughtful design, patient-centered assessment, and practical consideration of daily life converge to create devices that are both functional and meaningful. For those curious about how to navigate and apply such tools in practice, practical references on tools and equipment for occupational therapists provide accessible guidance and notional templates for selecting and customizing utensils to fit a client’s unique needs. Tools and Equipment for Occupational Therapists.

In sum, adaptive utensils are more than adapted pieces of hardware. They are instruments of independence, capable of reducing effort, supporting safe feeding, and enabling meaningful social participation around the dining table. They reflect a philosophy that values patient autonomy, practical functionality, and the social dimensions of daily life. By attending to grip, weight, angle, and texture, clinicians can help people transform mealtime from a daily challenge into a reliable, gratifying experience. This transformation, in turn, reinforces the broader mission of occupational therapy: to enable individuals to engage in what matters most to them, using tools that are as human-centered as they are practical. For those interested in a deeper look at material science and production considerations behind rehabilitation tools, see The Science Behind Rehab Supply: Properties, Production, and Applications.

From Sensors to Sessions: How Wearable Technology Reframes Occupational Therapy Tools

Wearable technology is quietly reshaping the landscape of occupational therapy, turning tools that once relied on eyes and intuition into instruments that continuously sense, learn, and adapt. Clinicians who previously relied on periodic assessments and patient self-report now have access to streams of real-time data that illuminate how daily tasks are actually performed in the patient’s natural environment. This shift does not replace the therapeutic relationship; it enriches it. The patient and therapist can collaborate around tangible signals—subtle changes in grip quality, speed of movement, tremor intensity, or postural alignment—that were once invisible between sessions. In practical terms, wearable devices such as sensor-enhanced gloves, garments embedded with motion or pressure sensors, and wristbands that track range and fluidity of motion allow therapy to graduate from the clinic into the patient’s daily life with fidelity. The result is a more precise map of functional ability and a more personalised road map for recovery, one that respects the patient’s routines, preferences, and lived experience while maintaining a clear focus on meaningful ADLs.

The real-time monitoring capacity of wearable technology stands at the heart of its promise. When a patient uses a therapy-focused wearable during a reach-and-grasp task, the device can quantify grip strength over repetitions, measure torque during pinching, and detect nuanced finger trajectories that reveal compensatory strategies. For the therapist, these metrics go beyond vague impressions; they become objective markers that can confirm progress, signal plateaus, or highlight subtle regressions long before the patient perceives them. This objective lens is especially valuable in upper-limb rehabilitation, where improvements can be incremental yet transformative in daily life. The data also support dynamic adjustments to therapy plans. If grip patterns show diminishing variability and reduced adaptability after a week, the plan can pivot toward tasks that reintroduce variability, challenge timed responses, or re-balance movement with symmetry. The patient experiences care that feels responsive rather than prescriptive, a nuance that often translates into greater motivation and sustained engagement in home programs.

The relationship between engagement and outcomes is well documented when wearables are deployed thoughtfully. Real-time feedback reframes practice from a passive repetition into an active dialogue. Patients receive immediate cues about performance—like how much force is needed to hold an object safely, or how long it takes to release and regrasp—which reinforces correct strategies and discourages compensations that may hinder recovery over time. The most impactful designs couple this feedback with accessible, user-centered interfaces. A device might translate complex kinematic data into intuitive color-coded signals or simple progress dashboards that fit naturally into everyday routines. When patients can see the connection between what they do during a short exercise session and the quality of the everyday actions they care about—putting on a coat, opening a cabinet, buttoning a shirt—the therapeutic work becomes inherently more meaningful.

Linking wearable data to tangible ADLs is essential. Consider the process of dressing, which requires coordinated finger control, hand strength, forearm rotation, and asynchronous movements from both limbs. A sensor-equipped garment or glove can track the rhythm of those movements during dressing tasks, revealing how often a patient uses compensatory shoulder elevation or trunk lean to achieve the same outcome. With this insight, therapists can tailor interventions to reinforce safer, more efficient strategies, and the patient gains a clearer sense of which micro-skills to target. Importantly, wearable data do not merely quantify capability; they illuminate reliability. Consistency across sessions—whether in a clinic or at home—predicts the transfer of gains to real-world performance. When the wearable confirms consistent improvements in grip stability during functional tasks, it strengthens both the patient’s confidence and the therapist’s conviction that practice is translating into daily independence.

A growing body of evidence supports the integration of wearables into OT practice, not as a standalone solution but as a complementary approach that augments traditional methods. Wearable sensors enable therapists to track the frequency and quality of repetitive movements in neurorehabilitation scenarios such as stroke recovery or post-orthopedic rehabilitation. In the context of movement disorders, these devices can monitor tremor amplitude, cadence, and the consistency of movement patterns, providing data that inform decisions about task selection, pacing, and resistance progression. The beauty of this approach lies in its ability to balance precision with empathy: data guide the plan, but the patient’s daily priorities shape the path forward. The patient’s engagement grows when therapy feels tailored, transparent, and responsive to fluctuations in mood, fatigue, or motivation—factors that often determine how well a home program is sustained.

The practical integration of wearables into occupational therapy also opens doors to near real-time collaboration between patients and caregivers. When a caregiver observes a patient struggling with a daily task, the wearable data can confirm whether the difficulty is task-specific, momentary, or tied to a broader trend such as fatigue or analgesia needs. In turn, therapists can coach caregivers on strategies that support independent performance without undermining self-efficacy. This collaborative loop reinforces a central tenet of occupational therapy: practice that matters is practice that translates into meaningful life tasks. The wearable framework makes practice visible, measurable, and negotiable, turning ambitious goals into accessible milestones well within reach.

Yet, these advantages arrive with considerations that require thoughtful navigation. Usability is not a luxury but a prerequisite. Devices must be comfortable, unobtrusive, and easy to don and doff, especially for individuals with limited dexterity or increased sensory sensitivity. The design must account for variability in hand size, grip pattern, and tremor, ensuring that sensors do not become a source of discomfort or a barrier to adherence. Privacy and data security are non-negotiable; patients must trust that their personal motion data, movements, and performance metrics are protected and shared according to consent. Clinicians, too, bear responsibility for interpreting data responsibly—avoiding over-interpretation, recognizing context, and blending quantitative signals with qualitative observations obtained during hands-on sessions.

The potential for home-based, sensor-guided practice is perhaps the most transformative aspect of wearable OT tools. Tele-therapy has gained prominence, and wearables provide the data backbone that makes remote monitoring credible. Patients can complete structured practice at home while clinicians remotely review performance trends, adjust difficulty, and set new targets. This model preserves the therapist’s expert guidance while granting patients the freedom to integrate therapy into their routines without the friction of frequent clinic visits. In practical terms, a patient might perform daily reach-and-grasp tasks while wearing sensors that track hand opening, finger coordination, and grip strength. The resulting dataset paints a picture of progress across weeks rather than isolated snapshots, allowing therapists to fine-tune progression, identify plateaus, and celebrate meaningful gains in real-world function.

As wearables become more sophisticated, the line between assessment, training, and engagement continues to blur in a productive way. Advanced analytics can synthesize movement data with contextual information—such as time of day, fatigue levels, and perceived effort—to generate personalized recommendations. For example, after detecting a pattern of slower initiation or diminished grip strength late in the day, a therapist might shift the sequence of tasks to quieter, steadier practice or introduce micro-breaks to optimize performance. The integration of wearable data with existing OT tools creates a cohesive ecosystem where technology acts as a silent partner, supporting therapists in delivering highly individualized care without sacrificing human judgment or compassion.

For clinicians seeking to deepen their understanding of technology’s evolving role in OT, a recent synthesis highlights how digital tools shape patient care. what-role-does-technology-play-in-enhancing-patient-care-in-occupational-therapy/ offers a concise overview of how digital interfaces, sensors, and data-driven feedback complement traditional approaches. what-role-does-technology-play-in-enhancing-patient-care-in-occupational-therapy/. This resource underscores a central theme of this chapter: wearable technology is not an end in itself but a facilitator of more precise, responsive, and person-centered therapy. It invites clinicians to envision OT tools as dynamic systems that adapt to the patient’s evolving needs, goals, and life context rather than static devices with a fixed function.

The horizon for wearable OT tools includes closer alignment with other modalities, such as virtual reality and augmented task environments. When sensors feed into gamified or VR-based practice, patients encounter tasks that are simultaneously enjoyable and therapeutically potent. The repetitive, goal-directed nature of such experiences fosters motor learning through meaningful context, thereby enhancing motor recovery and functional carryover. Importantly, the design philosophy must remain anchored in real-world relevance. Tasks should mirror everyday activities that patients value, so improvements translate into tangible independence rather than episodic gains during a therapy session. This alignment helps sustain motivation, which is often the most critical variable in rehabilitation outcomes.

In sum, wearable technology is expanding the toolkit of occupational therapy in ways that preserve the human-centered core of the profession while elevating the precision and relevance of practice. Real-time monitoring provides objective insight; data-driven adaptation makes therapy responsive; and patient engagement becomes a measurable driver of success. The chapter’s throughline is not novelty for its own sake but a thoughtful integration of sensing and care, where every motion logged by a sensor becomes a step toward a patient’s greater sense of autonomy. As the field experiments with richer data streams and more intuitive interfaces, clinicians will continue to refine how wearables complement traditional OT tools, weaving technology into the fabric of everyday life rather than treating it as a separate, isolated module.

External resource for further reading: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9046257/

Designing for Real Hands and Real Lives: The User-Centered Path to the Next Generation of Occupational Therapy Tools

Designing for Real Hands and Real Lives unfolds as a conversation among therapists, patients, and designers. It begins with a question: what do people need to do differently in daily life, and what would help them get there? In occupational therapy, tools are not merely gadgets; they are conduits of activity, motivation, safety, and independence. A user-centered approach places the person relearning a skill, the therapist guiding them, and the caregiver supporting routines at the heart of every design decision. The result is a cohesive suite of options that fits real workflows, adapts to changing abilities, and remains relevant across home and clinic environments. When designers observe therapy sessions, home practice, and everyday chores, they see friction points, data gaps, and opportunities for personalization. These insights drive solutions that feel intuitive from first use and stay relevant as rehabilitation progresses. The broader arc is not about more features, but about aligning technology with human needs, one iteration at a time. This approach maps workflows, tests ideas in real settings, and revises based on feedback about practicality, not just potential.\n\nIdentifying challenges becomes a disciplined act of listening. Designers watch how therapists capture progress, plan activities, and tailor exercises to goals. They notice that data collection can be inefficient when entered manually, consuming therapy time that could be spent with clients. They observe that home exercises must reflect home routines, living environments, and cultural preferences. They hear about engagement and motivation hinging on immediate feedback and meaningful tasks. These observations translate into core requirements that drive safer, more efficient, and more enjoyable tools. The design shifts from a purely technical specification to a collaborative assessment of what activities will be practiced, how information will be organized, and how users will learn to navigate new functionality without disrupting routines.\n\nA compelling pattern is the opportunity to empower therapists with practical, adaptable tools rather than rigid, one-size-fits-all systems. For example, an Android-based tool for occupational therapists can adopt a flexible framework that mirrors the therapist’s workflow, allowing quick data capture, intuitive dashboards, and automatic recording of outcomes for later analysis. The user-centered process emphasizes clarity and control: a portable, easy-to-use tool that slides into clinical routines. User evaluations confirm the system feels practical because it was designed with input from daily users. The tool respects the tempo of clinical work and the rhythm of patient progress, becoming a reliable ally.\n\nIn parallel, design for motor and speech rehabilitation focuses on motivation and home practice. A digital home exercise companion can provide easy review of home exercises, demonstration videos, and mechanisms that encourage ongoing practice without adding undue workload for therapists. Clinicians report improved efficiency and accountability as patients access demonstrations and track adherence between sessions.\n\nThe spectrum extends to the physical interface of assistive devices for tremors or limited dexterity. A continual, user-feedback-driven approach yields devices that are usable and comfortable, enabling tasks like dressing, meal preparation, and personal care with less assistance. These tools feel almost invisible in operation, yet their benefits accumulate in regained independence and reduced caregiver load.\n\nWearable technologies offer a bridge between intention and action. A lightweight armband can sense muscle activity and translate signals into meaningful commands, expanding opportunities for neurorehabilitation. The goal is to turn data into actionable feedback that motivates practice, with clinicians gaining timely insight to adjust difficulty and pacing without waiting for clinic visits. Wearables thus sustain practice, support personalization, and align technology with how people move and learn.\n\nThe broader implication is a more humane development path for occupational therapy tools. By foregrounding users’ needs, designers create technologies that integrate into practice, support personalized care, and sustain engagement across rehabilitation. This is not just theory; it translates into real-world benefits in clinics and homes. The field benefits when researchers and clinicians share what works, and when designers use those insights to refine software and hardware. The ultimate aim is to help people reclaim agency in daily life through tools that respect pace, priorities, and environments. The promise is technology that amplifies human capability without eroding dignity.

Final thoughts

The landscape of occupational therapy is rapidly evolving, with innovative tools enhancing rehabilitation processes. These tools are strategically developed to empower individuals in their recovery journey, fostering independence, engagement, and improved outcomes. Business owners in the healthcare sector should consider the substantial benefits these tools offer, not only in effective therapy but also in enhancing patient satisfaction and motivation. As technology continues to integrate into therapy practices, embracing these advancements stands critical in providing superior care to those in need.