Occupational therapy equipment plays a pivotal role in enabling individuals to achieve greater independence in their daily activities. Business owners in healthcare and therapy fields must understand the myriad tools available that can facilitate better patient outcomes. This article will delve into a detailed list of common occupational therapy equipment, highlighting their importance in patient care, exploring different types, providing visual references, and discussing future trends. Each chapter connects back to the central theme of improving therapeutic practices through the effective use of specialized equipment.

The Working Palette of Independence: An Integrated Look at Common OT Equipment with Pictures

Occupational therapy equipment functions like a carefully chosen palette for a painter who is relearning everyday life. Each tool serves a purpose in shaping movement, confidence, and independence, and when paired with clear visual references, they support both therapy planning and the learner’s understanding of the tasks ahead. The research materials gathered for this chapter describe a comprehensive lineup, organized not by brand name or trend, but by the kind of skill each item targets. This approach mirrors how therapists assess needs in the clinic and how families begin to imagine home practice. Pictures matter here, because a single image can anchor a new idea, illustrate safe technique, and reduce anxiety about unfamiliar tasks. When clinicians discuss goals with clients, they often return to concrete visuals to keep everyone aligned on progress and expectations. The collection that follows, while not exhaustive, reflects current best practices in occupational therapy and offers a cohesive map of the equipment landscape used to develop motor skills, support daily living activities, and foster cognitive and sensory integration. For readers who want a deeper dive into equipment choices and their practical applications, a visit to the practical overview of tools and equipment for occupational therapists can be illuminating, as it translates theory into everyday practice. For now, imagine moving through a well-ordered closet of supports, each item waiting to be selected for the person who is relearning to write, button a shirt, cook a meal, or balance on a wobbly surface with a steady spine. The power of these tools lies not in any single device, but in how they enable repeated, meaningful practice in real-life contexts. The following sections stitch together the core categories therapists rely on, presenting the tools in a way that underscores the connections between precise hand use, purposeful movement, safe independence, and the cognitive and sensory processes that accompany daily tasks.

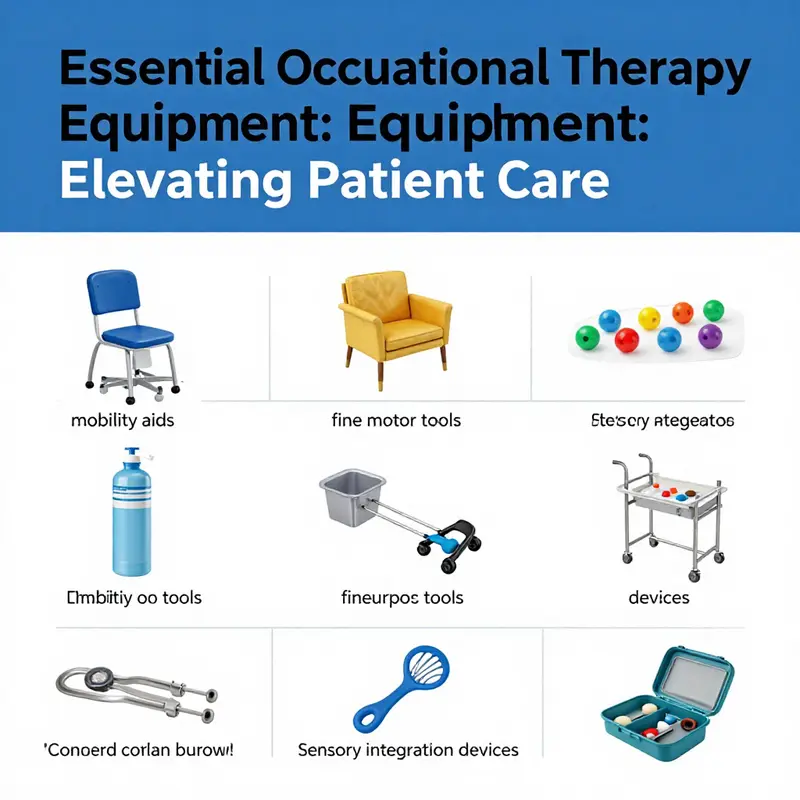

Fine motor skills, the delicate orchestra of finger, hand, and wrist movements, hold a pivotal place in many therapy plans. In this realm, the most common tools are those that train grip, pinch, precision, and coordination. Therapy putty, for instance, is a versatile, moldable material that comes in varying resistance levels. It offers a forgiving medium for activating intrinsic hand muscles, strengthening the thenar and hypothenar eminence, and refining finger isolation essential for handwriting, buttoning, and manipulating small objects. The resistance levels—light, medium, and heavy—allow therapists to tailor progression to a client’s current capacity, then steadily widen the range as grip strength and dexterity improve. Alongside putty, hand grippers provide a concrete measure of force-generation capacity. Squeezing against resistance helps build endurance in the forearm, improves finger flexor strength, and supports functional uses such as gripping utensils or turning a doorknob with less effort. Pegboards and pegs add a spatial, bilateral component to fine motor training. Insertion and removal of pegs require precise alignment, coordinated eye-hand control, and the ability to anticipate the next action. This seemingly simple task becomes a powerful activity for refining sequencing and motor planning, while also engaging proprioceptive feedback that strengthens the sense of body in space. Tweezers and pincers, though small in scale, cultivate precision and pinch strength. They invite careful manipulation of tiny objects, such as beads or buttons, and help clients transfer these refined skills to everyday dressing and self-care. The narrative of fine motor tools is not just about strength, but about control, timing, and the gradual return of confidence in tasks once taken for granted. The images that accompany these tools serve as a bridge between description and execution. A clear photograph of how a putty exercise is performed, or how a pegboard is oriented, helps a client visualize the motion before attempting it, reducing hesitation and embarrassment that often accompany early sessions.

ADL, or activities of daily living, training equipment focuses on the practical mechanics of self-care. Here the goal is to support independence in dressing, grooming, feeding, and personal care. Adaptive utensils provide a straightforward yet transformative improvement for people with arthritis, tremors, or limited hand strength. Utensils with built-up handles, weighted components, or special shapes can dramatically reduce effort and fatigue during meals. Built-in features like plate guards or non-slip bases keep food in place and reduce spills, contributing to dignity and safety at mealtimes. Dressing tasks present unique challenges, and devices such as button hooks and shoehorns streamline the process of getting dressed. For someone with limited reach or dexterity, a simple button hook can convert a two-minute struggle into a few calm, confident steps. Sock aids and dressing sticks extend reach and promote independence without bending or stooping, which is especially valuable for individuals with back or hip limitations. In the bathroom, safety features like non-slip mats and bath seats become essential supports. They create secure zones for bathing and grooming, reducing slip risks and enabling a person to practice tasks with greater assurance. When therapists design ADL practice, they often blend tools into functional routines—the user may simulate setting the table with adaptive utensils, or practice pulling on a sock with a sock aid while watching for balance cues. The overarching message is that independence grows from repeated, supported practice in familiar environments, backed by equipment that reduces effort and enhances safety. The visuals for these tools anchor understanding by showing the precise form and placement of each device in real-life tasks, helping clients anticipate and navigate new routines with less apprehension.

Upper extremity and coordination tools emphasize the kinetic chain from shoulder through forearm to hand. Weighted blankets or vests provide deep pressure input that can be calming and organizing for individuals with sensory processing differences or anxiety. The sensation of firm, even pressure across the torso can calm the nervous system, creating a better platform for working on motor tasks and cognitive demands. Resistance bands, with their adjustable tension, offer scalable means to strengthen the arms, shoulders, and back, while also promoting proprioceptive feedback during dynamic exercises. Balance boards and stability balls introduce a postural challenge that engages core control, leg alignment, and coordinated movement. They are especially valuable when the goal is to transfer strength and control from a supported position into more functional, upright activities. Through careful progression—moving from seated to standing poses and from stable to unstable surfaces—clients cultivate the balance confidence needed for daily activities such as standing at a sink to wash dishes or stepping onto a curb during a walk. In practice, caregivers and therapists use these tools to bridge the gap between quiet, controlled movements and the more complex motor sequences of real-world tasks. The accompanying images illustrate not only the equipment, but the correct body alignment and posture that maximize benefit and minimize risk. Clear visuals help clients imitate the recommended positions and cues during home practice, enhancing consistency and outcomes.

Cognitive and sensory integration tools remind us that therapy is as much about how we think as about how we move. Sensory bins, filled with materials like rice, beans, or sand, invite tactile exploration, sorting, and discovery, contributing to attention, discrimination, and problem-solving skills. Sorting and matching games, with blocks, cards, or shapes, challenge memory, concentration, and visual processing. Visual tracking tools—simple aids like moving targets or objects on a stick—train ocular motor control, essential for reading, writing, and sports awareness. The synergy among these tools lies in their capacity to engage multiple domains at once: a single task might blend hand dexterity with planning, sequencing, and attention to perceptual detail. In clinical practice, pictures of these setups are particularly helpful for families seeking to understand why therapy includes seemingly playful activities. They demonstrate how a tactile activity can translate into a meaningful daily task, reinforcing the connection between play and function.

In practice, the equipment list functions as a living guide rather than a fixed catalog. Therapists assess each client’s unique needs, preferences, and home environment, then combine tools to create an integrated practice routine. The goal is to cultivate a sense of mastery—every small achievement in gripping, buttoning, balancing, or sorting reinforces the client’s belief in their own capabilities. Accurate visuals support this journey by providing a reference that is less intimidating than a textual description, and by offering a concrete image of a target movement or task. The chapter’s images aim to show not just the device, but how it is used, encouraging correct technique and safe practice. When families review the plan, they can reference the same images to cue practice sessions, track progression, and celebrate incremental gains. The interconnection between skill-specific tools and the broader objectives—independence, safety, and meaningful participation in daily life—becomes clearer with each image and description.

Finally, it is helpful to acknowledge the broader ecosystem in which these tools operate. High-quality visuals play a crucial role in education and therapy planning. For readers seeking rich, professional imagery that corresponds with these descriptions, reputable resources provide extensive libraries of occupational therapy visuals. A well-curated collection of images can illuminate both the task and the correct form, making it easier for clients to reproduce movements safely at home or in school. The integration of visuals with practice helps keep therapy tangible and motivating, which in turn supports adherence to home programs and engagement in sessions. The journey through equipment and images is not about amassing devices; it is about building an accessible bridge to everyday independence.

To support ongoing exploration, one can consult a broader catalog of tools and equipment for occupational therapists, which offers a practical companion to the ideas presented here. For readers who wish to see representative visuals aligned with these concepts, an external resource featuring professional imagery complements the narrative and deepens understanding. And for those who want to glimpse the wide range of occupational therapy visuals that accompany these concepts, a reputable image library can be a valuable reference. The combination of textual guidance and visual exemplars helps translate theory into practice and strengthens the sense that independence is achievable through informed, collaborative effort. In the end, the equipment list with pictures is a map of practical possibilities—each item a stepping stone toward a more autonomous and confident daily life.

External resource: https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/occupational-therapy-tools

Internal reference for further reading: a broader overview of equipment and practices can be explored at tools-and-equipment-for-occupational-therapists.

Seeing to Doing: How an Illustrated OT Equipment List Bridges Understanding, Practice, and Independence

In occupational therapy, the equipment list is more than a repository of tools; it is a living language that therapists use to translate goals into tangible, actionable steps. When pictures accompany every item, that language becomes accessible to patients, families, and care teams. A well-curated collection of images helps orient everyone to what each tool is designed to accomplish, how it is used, and where it fits within a broader plan to improve daily functioning. This visual map supports clinical reasoning in real time and serves as a powerful educational aid in homes, clinics, and classrooms alike. It also underpins the collaborative nature of therapy, inviting patients to participate in decisions about their own care rather than passively receiving instructions. In this way, a robust equipment list with pictures reinforces the therapeutic alliance, a cornerstone of successful outcomes.

Central to the value of any OT equipment catalog is its contribution to functional independence. Therapists craft individualized interventions by selecting tools that target specific activities patients wish to regain or improve. For example, activities requiring fine motor control—like buttoning, tying laces, or manipulating small objects—benefit from tools that strengthen the hands and fingers. Therapy putty, with its pliable texture and resistance options, is one such tool. It offers adjustable difficulty, enabling graded challenges that slowly increase grip strength, finger dexterity, and precision of motion. The visual depiction of putty in various states of use helps patients understand progression: a softer formulation may be ideal for early rehabilitation, while firmer varieties can accompany later stages when control increases. Seeing these variants in pictures helps patients anticipate how their practice might evolve and what to expect from the therapy process.

Beyond strengthening, the equipment list highlights items that support motor planning and coordination—skills essential to coordinating movements across joints, muscles, and senses in everyday tasks. A carefully selected assortment of pegs, boards, elastic bands, and small-handled utensils offers practical avenues to practice reach, release, manipulation, and graded resistance. When pictures show a child or adult engaging with shape sorters or textured boards, caregivers can observe the deliberate sequences therapists encourage, such as exploring different textures, matching shapes, or coordinating hand and eye movements. These visuals demystify therapeutic activities and enable families to recreate meaningful practice at home, under guidance, without fear of doing the exercise incorrectly.

One of the most impactful roles of illustrated equipment lists lies in sensory integration. Many patients, particularly children, experience sensory processing differences that affect regulation, attention, and participation. Weighted blankets, sensory bins, and textured surfaces are common tools in this domain, designed to provide organized sensory input and promote calm alertness. Pictures that show how a weighted blanket drapes over the body or how a sensory bin invites hands-on exploration help families understand why these items are used and how they might be integrated into daily routines. The imagery communicates not just the tool but the intended state—reduced anxiety, steadier focus, and smoother transitions between activities. When caregivers can visualize how a strategy works, they are more confident implementing it consistently, which in turn enhances therapeutic effectiveness.

A comprehensive equipment list with images also serves as a practical decision-support resource for clinicians. Accurate identification matters. Therapists must select tools compatible with a patient’s goals, setting, and safety needs. This is where visuals shine. A picture of a textured sensory board, for instance, clarifies the surface features that influence tactile feedback and could determine suitability for a child with tactile defensiveness or sensory seeking. Likewise, images of vibration toys, when used to stimulate proprioception and muscle activation, can guide choices about intensity and placement. The ability to reference a pictured item quickly supports efficient assessments, reduces ambiguity, and accelerates the development of targeted treatment plans. In turn, patients benefit from a clear, coherent pathway that connects what they do in therapy to the tasks they aim to reclaim in daily life.

The value of pictures extends to education and empowerment. Visual references downstream from the therapist’s assessment translate into practical knowledge for patients and caregivers. When a family opens a care plan and sees labeled images of each recommended tool, they gain a concrete understanding of how practice fits into a routine. This transparency builds trust and encourages active participation in goal setting and home programs. As patients observe themselves performing a task with a pictured aid, they can compare their own performance to the demonstration, adjust strategies, and celebrate progress more readily. The result is a more engaging, collaborative journey toward independence, where the patient’s confidence grows as the list of tools becomes familiar and meaningful rather than abstract.

In practice, the integration of visuals with a detailed equipment list supports both standardized and personalized care. For complex cases—where multiple domains intersect, such as fine motor skills, executive function, and sensory modulation—the ability to map each goal to a corresponding tool through images aids in prioritization and sequencing. A broader catalog that includes examples like grip-enhancing utensils, adapted fasteners, or portable self-regulation aids allows therapists to orchestrate a layered intervention plan. Patients and caregivers can see how small practices accumulate into larger gains, reinforcing the concept that independence is built through steady, repeated engagement with appropriately challenging tasks. The pictures anchor these concepts in reality, turning aspirational goals into observable steps.

Another strength of the image-supported equipment list is its alignment with educational and care-settings beyond the clinic. In schools, early intervention programs, or home care, pictures help communicate expectations to teachers and family members who may not have formal OT training. A clear visual reference reduces the cognitive burden of understanding contraindications, safety considerations, and proper usage. It also helps guard against misapplication of tools, which can impede progress or risk harm. When caregivers know what each piece is for and can recognize it by sight, they are more likely to use it correctly, consistently, and with the patient’s taste and preferences in mind. This alignment across environments is essential for generalization of skills—an ultimate aim of occupational therapy.

The notion of a picture-enhanced equipment list also intersects with the practical realities of resource availability and planning. Therapists often face constraints that require prioritization of tools that offer multiple benefits or adaptable use across several activities. Pictures aid this decision-making by illustrating the versatility of items and suggesting potential activity ideas. A single, well-photographed object can spark numerous practice scenarios, from hand strengthening to sequencing to sensory regulation. For families, visuals provide a springboard for home programs that feel manageable rather than overwhelming. They enable stepwise progression, where a patient moves from a photographed display to a tangible, hands-on routine that feels both achievable and motivating.

Consider the broader implications for professional documentation and care coordination. When clinicians document a patient’s progress, including images of the equipment being used can enhance clarity for other providers, educators, and family members. Visuals accompany narrative notes and goal statements, offering a quick reference point that supports continuity of care across disciplines and settings. In assessments, photographs of equipment can illustrate the specific tools that informed decisions about treatment complexity and safety precautions. When the patient or caregiver revisits the plan weeks or months later, the images serve as a nostalgic and practical reminder of the journey, making the experience less clinical and more person-centered.

The creation and dissemination of a comprehensive equipment list with pictures also invites opportunities for professional development and knowledge sharing. Clinicians can learn from each other by reviewing how different tools are pictured and described, what usage cues are highlighted, and how these visuals translate into improved patient understanding. This collegial exchange strengthens practice standards and supports ongoing learning. In addition, families and students who access robust, image-rich resources gain lasting benefits by developing a visual literacy around therapy equipment. They begin to recognize patterns, anticipate needs, and participate more fully in the planning and execution of therapy at home and in school. The upshot is not merely better adherence to therapy tasks, but a deeper sense of agency for people navigating rehabilitation, recovery, and life with greater independence.

For professionals seeking to augment their practice with high-quality visuals, there are reputable avenues to source images that illustrate equipment clearly and accurately. In clinical and educational contexts, images that depict how each tool is used, what it feels like to manipulate it, and how it contributes to a task can be invaluable. While the internet hosts a wide range of visuals, the aim is to curate pictures that accurately reflect the equipment’s purpose, safety, and best practices. The goal is to foster understanding without overwhelming the viewer with extraneous detail. Images should be labeled simply and consistently, with captions that clarify the target activity, the expected outcome, and any important safety notes. When images are integrated into patient-facing materials, the language accompanying them should be accessible, concrete, and free of jargon, ensuring that families from diverse backgrounds can engage with therapy concepts meaningfully.

As this chapter threads through the broader article on an occupational therapy equipment list with pictures, the central takeaway is that visuals amplify both comprehension and participation. They translate clinical reasoning into everyday action, bridging the gap between assessment and daily life. They empower patients to envision themselves performing tasks they value—dressing, cooking, pouring a drink, or writing a note—by showing, not just telling, how the right tool can support competence. They support caregivers by giving them reliable, shareable references that demystify therapy and promote consistent practice. In short, pictures do more than illustrate; they enable action, sustain motivation, and anchor independence in the lived experience of daily living.

Internal reference for further reading and practical guidance on how to integrate visuals with equipment lists can be found at a resource that discusses tools and equipment for occupational therapists, offering a practitioner-facing perspective on selection, customization, and patient education. Integrating such materials into your practice can streamline assessments, enrich planning conversations, and strengthen the therapeutic alliance as you move together toward meaningful daily functioning. Tools and equipment for occupational therapists.

External resource: https://www.shutterstock.com/search/occupational+therapy+equipment

Equipping Recovery: A Cohesive Profile of Rehabilitation Tools for Skill Development in Occupational Therapy

Every chapter in this article about the occupational therapy equipment list with picture rests on a shared thread: equipment is not merely objects. It is a practical map of function, progress, and independence. When clinicians select tools, they translate goals into tangible steps. The items below are not endpoints; they are lanes on a journey toward regained autonomy. Each piece of equipment is chosen for how it can be used safely, how it can be adapted to a person’s living environment, and how it can be integrated into daily tasks that matter most to the individual. In pictures, these tools become accessible, giving therapists and clients alike a clear sense of what progress looks like and how effort translates into capability. This chapter travels through the main categories, tracing how each type supports rehabilitation and skill development across a spectrum of conditions, from post-injury recovery to neurological and musculoskeletal challenges. The aim is not only to list gear but to illuminate how its presence shapes the therapeutic encounter, motivates participation, and anchors daily life in small, achievable wins. Within clinical rooms, homes, and community centers, therapists tailor arrangements to the person, not the other way around. A single resistance band, a balance board, or a set of hand-function tools can become anchors for routines that rebuild confidence as surely as strength. When therapists describe these tools, they speak of progression: from guided tasks with present support to independent, self-directed practice, all while watching for cues of safety, fatigue, or emerging mastery. In the broader landscape, images that accompany these tools help bridge understanding for families and caregivers. Seeing a picture of an adaptive utensil or a task-specific simulator can shift uncertainty into a plan. It invites questions about how, where, and when to practice, and it clarifies the roles of supervision, guidance, and home practice. The equipment discussed here serves six intertwined therapeutic goals: rebuild strength, restore coordination, reestablish functional movement, support problem-solving in daily tasks, foster endurance for lengthy activities, and cultivate engagement and motivation. Each goal aligns with daily routines that matter to people: dressing, grooming, eating, writing, managing finances, commuting, and caring for others. The resonance of these tools is measured not only in measurable gains on a scale or in a test battery but in the quiet, durable shifts of everyday capability. Take resistance bands, for example. They come in a ladder of resistance that can be dialed up as a person’s strength grows and down as joints or tissues demand gentler loading. This simple elasticity offers controlled, progressive loading that can target specific muscle groups without the need for heavy equipment. A light band might support range-of-motion work after a shoulder procedure, while a heavier loop can build grip and forearm strength for tasks like turning a doorknob, lifting a pot, or stabilizing utensils during meals. The portability of bands makes them ideal for both clinic and home, turning a corner of a living room into an adaptable gym. Yet the technique matters as much as the resistance. Proper alignment, breathing, and joint scapular positioning all modulate outcomes and reduce risk. The narrative of resistance bands is a reminder that therapy is a careful conversation between body and activity, a calibration of load and purpose to mirror real-life demands. Balance boards and stability trainers tell a parallel story about control, orientation, and core strength. For people recovering from stroke or brain injury, balance work is not an optional add-on but a central thread of safety and independence. These tools challenge posture, weight-shift, and the integration of sensory input with motor action. The board may wobble under the feet, but with guided practice, clients learn to listen to subtle cues from their feet and ankles, to adjust their center of gravity, and to reclaim a sense of confident movement. On a more practical level, balance training translates into steadier gait, reduced fall risk, and the ability to negotiate uneven surfaces at home, on the street, or in the workplace. A therapist may pair a balance task with a dual-task scenario—naming items or counting while maintaining stability—to mimic the cognitive demands of daily life. Therapy mats and hand-function tools provide a sturdy foundation for floor-based practice and for fine motor re-education. A non-slip surface is essential for safety, but mats also define zones for different activities, from sit-to-stand transitions to kneeling tasks that are common in kitchen or bathroom environments. Hand-function tools—grippers, putty, finger splints—target dexterity and strength at the level of the fingers and hand arches. Grasp and release, pinch, and opposition now become refined skills practiced with repetition that feels purposeful. Putty offers tactile feedback and resistance that can be adjusted as a person’s precision improves, while finger splints protect joints during tasks that involve repetitive use. These tools matter because many daily activities hinge on the precision of the hand: buttoning a shirt, turning a key, gripping a pen or utensil, fastening a clasp. The design of adaptive devices and assistive technologies expands the field of possibilities for self-care. Specialized utensils with built-up handles, weighted cups, and built-in stability options enable independence during feeding. Dressing aids simplify zipper pulls, buttons, and hooks, reducing frustration and increasing the likelihood of trying again after a setback. Grooming tools adapted for one-handed use or limited grip turn a morning routine from a fragile negotiation with the body into a series of confident steps. And for those who need to access devices beyond the hand’s reach, computer access tools and switch-operated controls open avenues for communication, study, and work. The exchange between equipment and technology becomes a dialogue about independence, and therapists watch for how comfortable a person is using the tools in varied contexts. Exercise machines and functional training equipment broaden the scale from isolated muscle work to integrated performance. Pulley systems, parallel bars, and task-specific simulators translate gym-like benefits into activity trains that resemble real life. The focus is not only on strength but on the choreography of movement: how a patient coordinates hips, trunk, and limbs when transferring from bed to chair, or how glenohumeral motion supports reaching into a cabinet. The design of these systems fosters task-specific endurance, such as repeatedly lifting a bag from a shelf or practicing a simulated kitchen routine. Finally, electronic and digital therapy aids reflect the ongoing fusion of clinical practice and technology. Biofeedback devices provide real-time data about muscle activation, heart rate, and breathing. Virtual reality platforms create immersive environments where practice is engaging and safe, offering immediate feedback and adaptable difficulty. This blend of data and immersion helps therapists tailor challenges to the individual’s current capabilities, while maintaining motivation through interactive scenarios that resemble daily life. The digital layer also supports progress tracking beyond the clinic walls, enabling remote coaching and home programs that sustain momentum between sessions. Across these categories, the common thread is customization. A therapist will consider the person’s diagnosis, stage of recovery, home environment, and personal goals when assembling a toolkit. The picture accompanying each tool in a catalog becomes a practical cue for planning sessions and for communicating with family members who support practice at home. It is not enough to know that a device exists; it matters how it fits into the narrative of a client’s day. This is why the equipment list is more than a catalog. It is a living resource that guides assessments, informs treatment plans, and anchors the client in a sense of capability. It reminds us that rehabilitation is not a single event but a sequence of attainable steps, each built on the confidence that comes with repeated successful task completion. In practice, therapists proceed with a careful sequence. They begin with a functional assessment, observing how a client currently performs daily activities and where stumbling blocks appear. They then select equipment that aligns with specific goals—perhaps a series of hand-function tools to improve buttoning and writing, or a balance board to address fall risk while simulating older adult mobility. They document progress prompts, safety cues, and home practice instructions, ensuring the client and family know what to do when the therapist is not present. The environment also matters. Equipment that is portable, compact, and adaptable to small living spaces is especially valuable for home programs. When tools are easy to store and quick to set up, clients are more likely to engage in daily practice. The pictures that accompany these tools act as a bridge between the clinical setting and the home, helping families understand how a device can support routine tasks without becoming a barrier or source of confusion. This approach aligns with a core principle of occupational therapy: maximize independence while respecting safety, comfort, and personal preferences. The choices behind each tool reflect a philosophy that meaningful activity is a powerful driver of recovery. When a person can dress without assistance, prepare a simple meal, or manage personal care with a familiar utensil, the therapy is not abstract. It has become part of the person’s ongoing story of capability. For readers seeking a broader perspective on how therapists select, adapt, and combine equipment in real-world settings, consider the article on tools and equipment for occupational therapists. This resource offers a deeper look at how equipment choices evolve with advances in practice and with the diverse needs of clients. As you explore the collection of devices described here, remember that the images you see beside each item are not merely decorative. They are strategic prompts that help clinicians and families envision use, space, and daily rhythm. The equipment list with pictures is itself a teaching tool, a compact library that supports planning, communication, and shared understanding. It invites a collaborative conversation among therapists, clients, and caregivers about what is feasible, what is meaningful, and what signals progress. In the end, the measure of success lies in the person’s growing ability to perform essential tasks with less effort, less hesitation, and more confidence. The most powerful image is not a glossy product shot but the quiet smile that appears when a task that once felt insurmountable is accomplished with independence. External resources can offer fuller specifications and supplier insights for those applying the equipment in clinical or home settings. For more detailed product specifications, pricing, and supplier contacts, see an external resource such as World Rehabilitation Therapy Equipment Information (2025) at https://www.worldrehabequipment.com/.

Seeing Solutions: A Visual Tour of the Occupational Therapy Equipment List

Visual references do more than decorate a booklet or a slide deck. In occupational therapy, pictures of equipment act as a shared language among clinicians, clients, and families. They ground complex ideas about function in concrete images, helping everyone understand how a tool might support daily tasks, from reaching a cup to buttoning a shirt. A well-curated equipment list, presented with clear visuals, becomes a roadmap for assessment, planning, and progressive intervention. It invites curiosity, lowers anxiety about unfamiliar devices, and invites clients to picture themselves using the tools in familiar settings. The equipment itself is more than hardware; it is a bridge between what a person can do today and what they can reliably accomplish tomorrow. When those bridges are shown visually, the journey from impairment to independence feels navigable, collaborative, and hopeful. In this chapter, we move through a representative roster of common occupational therapy tools, not as a catalog of gadgets but as a tapestry of strategies designed to cultivate everyday competence. Each item, grounded in evidence and clinical practice, is chosen for its potential to support motor control, balance, coordination, and the performance of daily activities. The power of the visual reference lies in the clarity it provides about how a tool fits into a task, what a successful session might look like, and how progress can be tracked over time. Consider a therapy ball, for instance. A large, resilient sphere is not merely a playground prop; it is a platform for challenging the core, stabilizing the trunk, and refining upper-extremity coordination. The image of a client seated on or gravitating toward a therapy ball conveys not only the target outcome—improved postural control and endurance—but also the dynamic nature of the work: weight shifts, responsive adjustments, and timed interactions with gravity. When clinicians share this image with a family, they illustrate a path to home practice that remains faithful to the therapeutic intent while inviting the client to engage in meaningful cues from daily life. The same logic extends to balance beams, which, in pictures, embody the progression from basic stability to controlled travel. Visual references show how small shifts in weight can teach the nervous system to regulate posture while the feet negotiate narrow pathways. The beam becomes a metaphor for cautious experimentation, where safety is emphasized and milestones are visible in the patient’s gait, foot placement, and tempo. The pictures capture subtle cues—how a knee aligns with the hip, how the arms reach for balance, how the breath steadies as the gaze stays forward. For the client, seeing these cues in a photograph or illustration reduces mystery. For the therapist, the image is a quick checklist, a reminder of the sequence of steps that make up a functional balance strategy. The narrative continues with stepping stones, portable platforms that simulate uneven terrain and challenge dynamic balance. In a clinical image, stepping stones look deceptively simple, a row of flat surfaces arranged at varying heights. Yet within the frame is a narrative of anticipation and adaptation: the client anticipates the next platform, recalibrates foot placement, and uses hand support only as needed. The visual reference communicates not only the goal—improved adaptability to changing surfaces—but also a process: engage, adjust, recover, and proceed. This is not about conquering a single task but about expanding the repertoire of safe, confident movements across environments. Moving from balance to grip, the collection includes grip strengtheners, including hand dynamometers and squeeze tools. The photograph or diagram of these devices translates strength into a task-aligned story. It shows how a performer transitions from securing a grip for a basic daily act—holding a cup or turning a key—to more intricate maneuvers such as manipulating small fasteners or opening a jar. The images may highlight how the hand assumes a functional shape, how pressure is distributed across the palm and fingers, and how practice with resistance can translate to less fatigue and more endurance in real life. In clinical practice, a powerful image of grip work also helps family members envision how to support practice routines at home, what to monitor for signs of fatigue or maladaptive strategies, and how to adjust activity demands as strength evolves over weeks and months. Tactile boards and sensory panels sit at the interface of touch and cognition. For children and adults with sensory processing differences, pictures of tactile exploration convey a world where textures become language. The images illuminate how varied surfaces—smooth, rough, ridged, and bumpy—offer opportunities for graded exploration, fine motor control, and focused attention. These visuals speak to clinicians and caregivers about the pacing of sessions, the safe introduction of sensory challenges, and the strategies to help a client tolerate new textures during daily tasks like dressing, grooming, or meal preparation. When the board is presented in a picture, its potential for therapeutic play becomes instantly legible: a child can predict how a task might unfold, a parent can anticipate calming strategies, and a therapist can tailor the sequence to align with developmental goals. Adaptive utensils, or ergonomic cutlery, bring independence to meals for those with limited hand function due to stroke, arthritis, or cerebral palsy. The visual representation of these tools highlights ergonomic handles, pivoting spoons, and weighted or angled designs that reduce strain and improve control. Pictures show how a modified grip reduces tremor and fatigue, enabling a person to scoop, lift, and modulate bite size with greater confidence. The imagery communicates an everyday metallic or ceramic ritual as something that can be mastered with agency rather than something endured through fatigue. Writing aids—wrist supports, slant boards, and specialized pen holders—appear in pictures as practical allies for legibility and comfort. The visuals demonstrate how support structures align the wrist, how slant boards angle the page to reduce awkward wrist extension, and how a pen grip stabilizes the index finger and thumb. These images are essential for clients who fear pain during handwriting or who have difficulty maintaining a steady letter formation after an injury. In the story the body tells through these pictures, handwriting becomes a shareable goal: clearer communication, less strain, and a route to greater confidence in school, work, or daily correspondence. Upper-extremity training devices—resistance bands and pulley systems—round out the collection with a focus on range of motion, strength, and coordination. Visual references show the variety of resistances, the correct alignment of the shoulder and elbow, and the way a patient leverages gravity to gain external flow of movement. The imagery communicates the gradual, progressive nature of therapy: from gentle, controlled movements to more expressive, functionally meaningful ranges of motion. Taken together, these tools form more than a shopping list. They create a shared visual language that supports assessments, treatment planning, and patient education. In practice, the pictures become part of the documentation palette, marking progress with a fast look at a familiar pose, a steady grip, or a confident transfer. The result is a coherent narrative in which a clinician’s notes, a family’s questions, and a client’s goals interlock around concrete images of capability. As the visual catalog evolves, clinicians can pair each image with a practical activity plan and a progression ladder, ensuring that what is pictured translates into what is practiced in therapy sessions and eventually into what is performed at home or in the community. This seamless integration—image, task, and outcome—maps directly onto the core aims of occupational therapy: to promote independence, safety, and meaningful engagement in daily life. For readers who want to explore how a practitioner selects and sequences tools, a deeper look at the broader set of available equipment and the rationale behind choosing particular devices can be found in the resource that discusses tools and equipment for occupational therapists. The visual references provided here are intended to complement that guidance, offering concrete images to accompany the written descriptions and to spark conversations about home adaptations, school supports, and community participation. In practice, these visuals also support culturally sensitive education, as families from diverse backgrounds may respond more readily to images that reflect familiar contexts, activities, and environments. Clinicians often tailor the pictured items to the client’s living situation, ensuring that the equipment list remains relevant rather than theoretical. The ultimate value of a picture-led equipment list lies in its ability to invite curiosity while clarifying expectations. It helps a client imagine what success could look like in a kitchen, a classroom, a bathroom, or a living room. It aids a caregiver in recognizing which tools might be introduced first, what cues might signal readiness for progression, and how to set realistic timelines for achieving durable independence. The images thus become a form of social storytelling, where the patient’s daily life is foregrounded, and therapy is presented as a practical pathway to that life. To close the loop between vision and practice, the chapter intentionally centers on how pictures support learning, assessment, and collaboration among all stakeholders. By grounding each tool in a clear function and a recognizable activity, the visual reference becomes more than a descriptor; it becomes a rehearsal space for daily life. For anyone crafting patient education materials, clinic handouts, or classroom demonstrations, these images serve as anchors that keep the focus on meaningful performance rather than isolated technique. If you’d like to explore practical ways to curate and present such visuals in your own setting, you can consult the internal resource on tools and equipment for occupational therapists, which offers guidance on selecting images, pairing them with activities, and aligning visuals with goal setting. External references that illustrate how these tools appear in real-world contexts can be found in reputable image collections that showcase therapy scenes and equipment in professional environments, further enriching understanding for teams, clients, and families.

Imagery and Innovation: Envisioning Wearables, AI, and Smart-Home Tools in the Future OT Equipment List

The chapter you are about to enter moves beyond a static catalog of devices. It explores how an occupational therapy equipment list, paired with clear pictures, can evolve into a living, data-informed map of functional possibility. The future that unfolds here is not just about adding gadgets; it is about rethinking how equipment supports independence, how pictures teach and persuade, and how digital intelligence weaves together therapy in the person’s daily life. In practice, the equipment list you rely on today functions as a shared language among therapists, clients, caregivers, and educators. It documents what is available, clarifies what each tool can accomplish, and helps plan activities that translate therapeutic gains into real-world tasks. As we look ahead, the list expands from tangible devices to an integrated ecosystem where wearables, artificial intelligence, and smart-home technology become normal allies in rehabilitation. Pictures will play a central role in this shift, not merely as illustrations but as dynamic aids that help people visualize use, anticipate challenges, and see the potential pathways toward greater independence.

The first force shaping the future OT equipment list with pictures is the integration of wearable technology. Wearables, when thoughtfully designed for everyday activities, provide therapists with continuous streams of movement data, posture cues, energy expenditure, and even physiological signals such as heart rate and respiration. The value lies in turning episodic clinic observations into a 24/7 portrait of how a person engages with the world. A well-curated picture-led equipment list can showcase wearables not as lab devices but as everyday companions—armbands that gently monitor tremor during dressing tasks, vests that sense spinal alignment during standing transfers, or smart insoles that log weight distribution during cooking and cleaning. These images can capture how a device sits on the body, how it interfaces with clothing, and how a user might transition from one activity to another. For clients and families, pictures offer a concrete sense of what a wearable looks like in real life, what to expect during use, and how data might be interpreted by a therapist to adjust goals. The data stream from wearables empowers personalized therapy plans, enabling therapists to tailor progression criteria with precision while maintaining sensitivity to the client’s preferences and daily rhythms. This convergence of visuals and data also supports collaborative decision-making. A clinician can point to a picture of a tactile sensor placed at the wrist during grooming, compare it with a user’s current routine, and jointly decide whether to trial a different placement, adjust the activity sequence, or increase repetition. The pictures serve as reference anchors in ongoing conversations about safety, comfort, and autonomy.

A second transformative trend is the rise of AI-powered rehabilitation devices that extend therapy beyond clinic walls. In the coming years, artificial intelligence will help interpret the data captured by wearables and digital interfaces, transforming how feedback is delivered and how exercises are prescribed. Picture-driven catalogs will begin to depict AI-assisted tools that provide real-time, adaptive guidance. Imagine a picture that shows a tablet or small display paired with sensors, offering prompts like “adjust grip” or “modify elbow angle” while an activity such as meal preparation or laundry is demonstrated in the accompanying photograph. The AI component can learn a person’s pattern of performance, recognize when a task begins to fatigue the user, and suggest graded challenges that match the rate of improvement. The result is a more interactive, responsive rehabilitation experience where the device supports self-management. For clients who have difficulty recalling instructions, AI-enabled interfaces can deliver concise cues aligned with the exact moment a task is performed, making practice more efficient and less frustrating. Importantly, these devices are not stand-alone gadgets; they function within a broader therapeutic framework that uses pictures to explain purpose, safety, and expected outcomes. Visual guides reinforce learning, set realistic expectations, and offer reassurance that the guidance is personalized rather than generic.

Smart home integration represents the third wave driving evolution in the future OT equipment list with pictures. As homes become smarter, the boundary between clinic-based therapy and daily living blurs in constructive ways. Pictures on the equipment list can illustrate how assistive technologies connect with everyday environments—from kitchen counters to bedroom layouts—demonstrating how therapists envision independence in familiar spaces. In practice, this means curating devices that can communicate with smart speakers, lighting systems, door sensors, and environmental controls, all designed with accessibility in mind. The pictures that accompany these descriptions help clients understand not just the device itself but the context in which it operates. A photograph of a sensor-enabled cabinet that recognizes a user’s reach distance during a cooking task, paired with a diagram of the suggested sequencing, can illuminate how a chore becomes safer and more manageable. The goal is to enable therapists to design home-based practice plans that clients can actually implement with confidence, turning therapy into a steady, sustainable pattern rather than a temporary program. Remote monitoring features, enabled by smart-home ecosystems, allow therapists to observe consistent performance and intervene when progress stalls. In this way, the equipment list functions as a bridge between clinical insight and home-based practice, with pictures bridging understanding across diverse audiences—children, adults, and older adults alike.

These trends are not merely about adding gadgets; they also carry a set of design and practice considerations that ensure the equipment list with pictures remains accessible, ethical, and useful. First, the design of wearables and AI aides must emphasize comfort and safety. Pictures should capture correct placement, common pitfalls, and strategies to adjust the device for different body sizes and abilities. The visual material should also communicate potential risks, such as skin irritation or glare from screens, so that clients and caregivers can proactively mitigate issues. Second, data privacy and consent should be foregrounded in both the narrative accompanying the pictures and the accompanying training. Visuals can show consent steps in action, such as how data is stored, who has access, and how users can opt out. Clear captions can translate technical privacy terms into everyday language. Third, accessibility remains essential. Pictures must reflect diverse body types, ages, and reframing strategies for people with sensory or cognitive differences. This means captions that are precise but easy to understand, alt-text for digital catalogs, and opportunities to customize the visual presentation for different learners. Fourth, affordability and equity should guide the selection and presentation of equipment. The future list should feature scalable options, with pictures illustrating progressively complex setups—from basic assistive tools to integrated smart-home configurations—so clinicians can plan tiered interventions aligned with each client’s resources and goals. Finally, the clinical workflow must adapt to these innovations. Documentation practices should evolve to capture not only the device name and function but also the specific scenarios depicted in the pictures: the activity, the environment, the body mechanics involved, and the observed outcomes. A picture-rich catalog that supports clear, concise notes will be a powerful ally in treatment planning and progress tracking.

To maintain coherence between what is pictured and what is practiced, clinicians will increasingly rely on standardized visual metaphors. A simple, consistent visual language helps clients interpret reminders, reminders, and progression cues across devices and settings. A photograph of a kitchen task, a short video clip for a hand-strength exercise, or a schematic showing sequence steps can all anchor a client’s understanding. The benefit of such consistency is not limited to clients; it extends to families and caregivers who are part of daily routines. When pictures show how a device integrates into a typical day, caregivers gain confidence in supporting practice outside formal sessions. The resulting collaboration strengthens adherence to therapy plans, reduces uncertainty, and encourages clients to take ownership of their improvement.

In this evolving landscape, the role of the therapist also shifts. The image-rich equipment list becomes a living document that therapists update with new insights gained from practice and research. It invites ongoing dialogue about what works for whom, what risks require mitigation, and how to present complex information in a digestible, actionable way. The pictures are not merely decorative; they are functional tools that simplify decision-making, support shared understanding, and invite a broader circle of readers—family members, teachers, employers, and community members—to participate in the client’s journey toward independence. When used thoughtfully, the future equipment list with pictures can transform the therapy experience into a transparent, collaborative process that aligns with each person’s daily life, values, and aspirations.

A practical note ties this vision back to everyday work. You may begin to curate your growing repository of pictures with attention to common activities that often define participation in daily life: dressing, meal preparation, personal care, mobility, and social engagement. For each activity, pair a routine description with the corresponding equipment image, plus a brief caption that explains how the device supports the task, what to watch for in use, and how progress will be measured. The narrative around the pictures should emphasize flexibility—the ability to adapt devices and strategies to changing needs, preferences, and environments. This approach ensures that the list remains relevant across ages and conditions, from early childhood through geriatrics, and across settings such as homes, schools, clinics, and workplaces.

As readers consider these ideas, a linked resource highlights the broader role of technology in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy. For deeper context on this topic, see the discussion here: What role does technology play in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy. The integration of technology is not a novelty but a trajectory that carries with it responsibility, empathy, and a clear commitment to client-centered outcomes. While the specifics of products will continue to evolve, the central promise remains stable: when pictures illustrate capability, and when devices align with real-life activities, therapy becomes more accessible, more engaging, and more transformative.

The chapter concludes with a forward-looking invitation. Picture the equipment list as an evolving atlas that maps the practical landscape of daily life and its barriers. The future atlas will be richly illustrated, featuring wearables that blend seamlessly with clothing, AI-guided rehab stations that respond to user input with precision, and smart-home configurations that extend therapeutic gains into the living environment. Each image will tell a story—of a person learning to load a dishwasher, to stand safely at a counter, to navigate a corridor with confidence. The story will not be told by devices alone but by the human experience they support, captured in photographs that depict movement, intention, effort, and achievement. In that sense, the future OT equipment list with pictures is not merely a catalog of tools. It is a narrative of growing independence, a visual guide to progress, and a shared framework for meaningful participation in everyday life.

External resource: For a broader understanding of technology’s role in occupational therapy care and practice, consider reviewing resources from a leading professional organization at https://www.aota.org.

Final thoughts

Understanding the diverse range of occupational therapy equipment is essential for enhancing patient care and promoting independence. Each piece of equipment serves a specific function that can aid in rehabilitation and skill development. As business owners in the healthcare sector, investing in these tools not only benefits your practice but also significantly improves patient outcomes. Staying updated on current and future trends in OT equipment is vital for remaining competitive and ensuring the best care for clients.