Occupational therapy (OT) supplies are fundamental tools that support individuals in regaining their ability to perform daily activities. They play a critical role in therapeutic practices across various demographics, particularly in rehabilitation settings. Business owners in the healthcare and therapy sectors must understand the importance of these supplies, as they directly influence treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction. From fine motor skill enhancement to environmental modifications, each chapter will explore key categories of OT supplies and their functions, empowering businesses to provide effective and targeted solutions for patients in need.

Dexterity as Everyday Mastery: Exploring Fine Motor Development Tools in Occupational Therapy Supplies

Fine motor skill development sits at the heart of occupational therapy’s mission to restore and sustain independence in daily life. When therapists assemble a toolkit of OT supplies, they are not simply stocking a shelf; they are designing a pathway from clumsy, hesitant movements to confident, precise actions. The tools themselves—ranging from sensory-rich fillers to grip-enhancing implements—are chosen and sequenced to deliver graded challenges that respect each person’s pace, abilities, and goals. In this sense, fine motor development tools function as bridges. They connect the sensation and strength training that happens in therapy rooms to the moment a person reaches for a spoon, threads a button, or stamps a letter with legible handwriting. The chapter that follows traces how these supplies operate within a cohesive, patient-centered plan, and why their thoughtful selection matters for outcomes across ages and diagnoses.

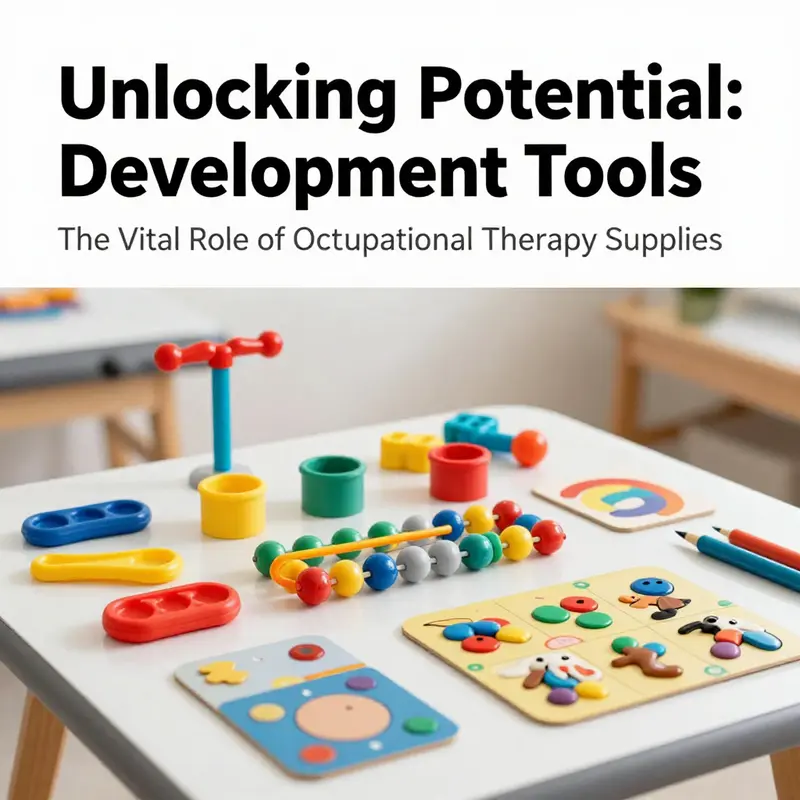

At the core of any fine motor program is the recognition that precision begins with stable sensory input and controlled proximal support. Therapists may begin with tools that invite large, gross movements and progressively narrow the focus to isolated finger control. This progression is not arbitrary; it mirrors the neuromuscular reorganization that must occur for fine tasks to become automatic. Sensory bin fillers, for instance, provide a playful but purposeful medium for practicing grasp, release, and bilateral coordination. A typical session might invite a child to scoop, pinch, and transfer small objects using a set of padded implements—plastic tweezers, silicone tongs, and other manipulatives—within a tactile, visually engaging bin. The goal is to stimulate grasp patterns without overwhelming the hand and to cultivate finger isolation through repeated, meaningful actions. Such activities do not merely strengthen muscles; they refine timing, sequencing, and force modulation, all of which contribute to smoother handwriting, safer tool use, and more reliable self-care.

Therapy putty occupies a similar but distinctive niche in the fine motor landscape. Its graded resistance supports progressive strengthening of the intrinsic and extrinsic hand muscles while encouraging controlled movements. As resistance increases from soft to firm, the user must modulate grip force, finger dexterity, and wrist stability. This is more than a strength exercise; it is a neuromotor re-education process that translates to everyday precision. A therapist will guide a client through a series of arcs—pinching, rolling, and isolating individual fingers—while watching for compensatory patterns that could inhibit genuine skill growth. The beauty of putty is its adaptability: it accommodates a spectrum of ages and abilities, from children with developmental delays to adults recovering from injury, and it can be used in short, focused bursts or longer, task-oriented sessions. The result is not just stronger fingers but more deliberate, controlled movements that carry over into complex activities like writing, buttoning, or opening a tightly sealed jar.

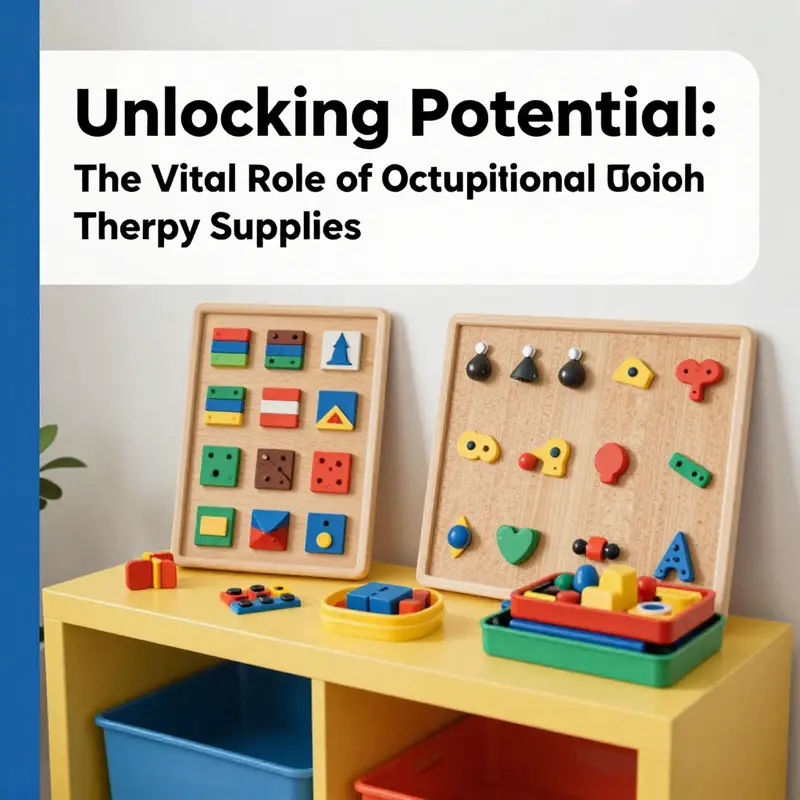

Textured sensory boards further enrich this fine motor journey by providing tactile feedback that supports sensory integration and motor planning. The textures—ranging from smooth to ridged, from soft to coarse—invite nuanced finger exploration. As users interact with different surfaces, they practice graded finger pressure, proprioceptive awareness, and precise placement of the pads of their fingers. The boards also invite a kind of cognitive-motor coupling: deciding which texture to press, how to adjust pressure, and when to switch tasks. This cognitive layer is essential, especially for children who may grapple with sensory modulation or attention challenges. By blending touch with purposeful manipulation, textured boards become quiet tutors in the development of hand-eye coordination, visual-spatial processing, and the steady, minute movements that underpin penmanship and tool use.

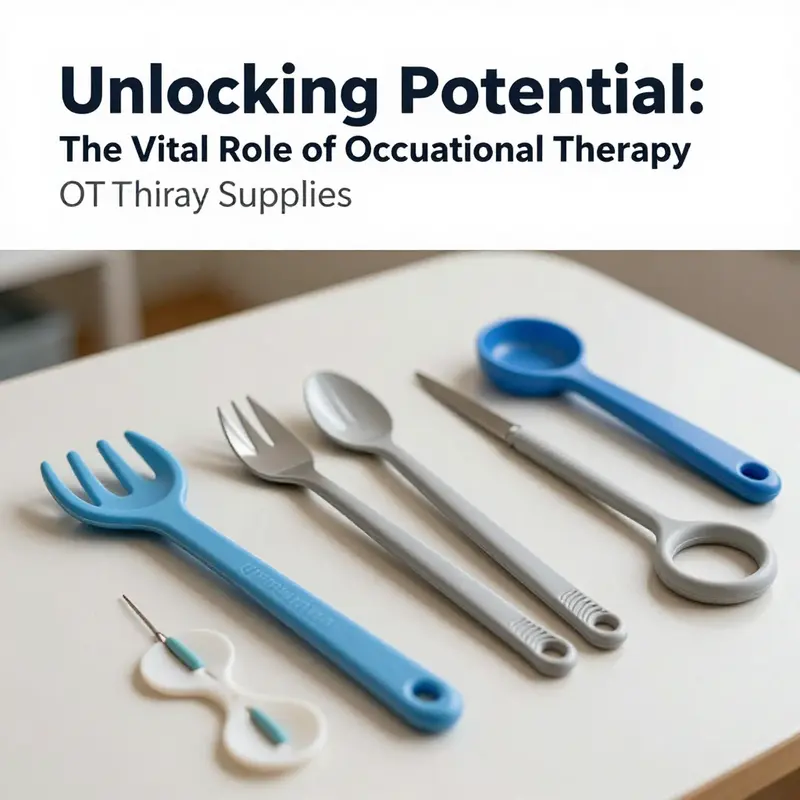

Incorporating weighted utensils and adaptive writing aids adds another dimension to fine motor practice. For some individuals, instability or tremor makes daily manipulation feel like a test of endurance. Weighted utensils provide the stabilizing inertia that permits more controlled handle-to-food contact or instrument control, enabling smoother transfers and more confident self-feeding. Similarly, adaptive writing tools—grip-enhanced pencils, angled tips, or built-up handles—reduce the effort required to produce legible letters and aligned strokes. The central aim is not to eliminate effort but to optimize it so that the hands can engage in the task with less fatigue and fewer compensations. When these aids are introduced thoughtfully, they do not become crutches; they unlock capacity, allowing clients to experience success and build further skills through repetition and feedback.

A comprehensive fine motor program also embraces the real-world scaffold of daily activities. In many settings, therapists design tasks that mimic kitchen routines, dressing tasks, and craft projects to connect the therapy room to home life. Kitchen simulators, dressing aids, and craft stations serve as concrete stages where improved hand control translates into practical outcomes. For example, a child who once struggled to manipulate a zipper might, after several weeks of using textured boards and pinching exercises, demonstrate smoother, more confident zipper pulls. A teenager learning to manage a self-feeding routine can advance from bulky cutlery to more precise utensil control, aided by adapted grips that fit their hand size and strength. These functional tasks become windows into broader independence, expanding the child’s or adult’s sense of what is possible in everyday living.

The environment in which therapy occurs amplifies the impact of these tools. In an Occupational Therapy Room (OT Room) at established rehabilitation facilities, purposeful activity spaces are carefully curated to facilitate meaningful practice. A well-designed OT Room offers functional simulation zones, such as kitchen and bathroom setups, that resemble real-home contexts. Alongside these are craft and manual workstations that encourage hand-eye coordination, spatial reasoning, and executive functioning through purposeful, activity-based interventions. The layout supports a predictable, safe flow from one task to another, reinforcing the idea that therapy is not a isolated exercise but a sequence of real-life challenges met with growing competence. In this setting, the tools do not exist in isolation. They are integrated into a cohesive plan aligned with safety standards—non-slip flooring with a coefficient of friction at least 0.6, rounded edges on furniture, and attention to grip safety—so therapists can push for progress while maintaining a secure environment. This integration matters because it bridges the gap between what happens during therapy and how a person applies those gains at home, school, or work.

An essential element of successful fine motor work is personalization. Pediatric clients require tools sized to their growing hands, with resistance and textures matched to their current abilities and future goals. Adults recovering from injury or managing neurological changes need options that accommodate changes in grip strength, tremor, and coordination. Therapists tailor the combination and progression of tools to reflect a person’s unique profile, typically starting with simple, high-sclar tasks and incrementally adding complexity. This approach fosters motivation and confidence, which are as critical to progress as the physical capabilities themselves. When therapy is guided by patient-centered goals, the supply shelf becomes a dynamic ally, not a static collection of devices. The result is a program that honors each person’s pace and celebrates incremental gains while staying firmly anchored in functional relevance.

Evidence undergirds these practice choices. Case-Smith’s work in pediatric occupational therapy underscores that targeted, age-appropriate fine motor interventions yield meaningful improvements in daily living activities. The emphasis on tailoring tasks to the developmental stage and the individual’s neurological profile helps explain why even small adjustments in tool selection or task demands can yield outsized gains in independence and confidence. The Ohio State resource on fine motor development further codifies evidence-based practices and delineates practical considerations for tool selection and progression. For readers seeking a structured overview that complements clinical experience, this resource serves as a credible touchstone that aligns with the hands-on strategies described here. For more on the evidence-informed framework guiding these tools, see the Ohio State resource on fine motor development. Ohio.edu fine motor development resource

Beyond the clinical pages, the broader field of occupational therapy emphasizes the interdependence of sensory input, motor control, cognitive planning, and environmental supports. The same toolkit principles that empower children with developmental delays or after orthopedic injuries also address adults facing life changes after stroke or spinal conditions. Fine motor supplies are not merely about repetitive motion; they are about shaping the neural pathways that govern precise control, timing, and fluidity of movement. Each tool, when used thoughtfully, affords incremental challenges that invite the nervous system to recalibrate. This recalibration, in turn, enables more efficient and independent performance of tasks that once required supervision or assistance.

Finally, the narrative of OT supplies in fine motor development is not about chasing novelty. It is about aligning tools with everyday function, patient goals, and evidence-based practice. The chapter’s focus on sensory input, grip control, and task-specific practice reflects a philosophy that has endured across generations of therapists: meaningful activity drives change more reliably than isolated strength work. When therapists curate a space in which a child can explore textures, practice controlled pinches, and manipulate utensils within the safety of a well-designed room, they are not merely teaching technique. They are shaping autonomy. The subtle art of tool selection, the careful calibration of resistance and texture, and the deliberate sequencing of tasks all contribute to an improved quality of life—the ultimate objective of OT therapy supplies.

For readers who wish to explore the scientific context that informs these practice choices, look to the broader literature on sensory integration, fine motor control, and developmental rehabilitation. The evidence base emphasizes the importance of consistent use under professional guidance, appropriate sizing, and individualized treatment planning. In this light, OT supplies become a coordinated system—one that supports growth, fosters independence, and helps clients translate therapy gains into lasting, real-world capabilities. As therapists and researchers continue to refine these tools, the underlying message remains clear: with carefully chosen supplies and carefully crafted tasks, fine motor development can open doors to everyday mastery and increased participation in the activities that matter most.

External resource: For broader context on sensory integration and motor development in autism, see the CDC resource on autism and learning supports, which provides foundational information on how sensory processing can influence daily motor performance and strategies for supporting development. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html

Functional Task Training Equipment: Crafting Independence Through OT Therapy Supplies

Occupational therapy hinges on a simple yet powerful premise: people regain independence when therapy translates into real life. Functional task training equipment sits at the heart of this translation. It is not a collection of random tools but a thoughtfully organized array of devices and setups that mirror everyday tasks. When a patient reaches for a dressing trainer to practice buttoning a shirt, or chooses an adaptive eating utensil to manage a tremor during a meal, the therapy room becomes a rehearsal stage for home life, work, and community participation. The objective is not to perform chores for its own sake but to rebuild the sequence, timing, and confidence needed to complete those chores with less effort and more control. In this light, functional task training equipment is both the canvas and the scaffold of daily living rehabilitation.

Dressing trainers, adaptive utensils, grip strength trainers, simulated kitchen setups, and a range of bathing and toileting aids form a cohesive constellation of tools that address the core components of functional independence. Each category targets a specific facet of performance. Dressing trainers extend the reach of autonomy by offering larger grips and modified mechanisms that accommodate limited dexterity or reduced range of motion. They allow a person to practice the motor sequences involved in dressing — reaching, buttoning, zipping, and tucking — with fewer frustrations and more accurate feedback about what needs adjustment. Adaptive eating utensils, with built-up handles or weighted features, reduce the force and fine control required to bring food to the mouth, supporting individuals with tremors, arthritis, or other motor challenges to participate in meals with dignity and safety. Grip strength trainers and hand exercisers provide a focused, measurable way to rebuild pinch and grasp strength, essential for manipulating small objects, opening containers, and coordinating the fingers in sequences that attend daily tasks demand.

The kitchen, often the most challenging arena for independence, becomes a controlled laboratory through simulated kitchen setups. A patient can practice chopping, pouring, measuring, and cooking in a safe, adjustable environment that mimics the texture and resistance of real-world tasks without the hazards of a real kitchen. Such simulations enable therapists to observe planning, sequencing, and problem-solving as they unfold in a task context, rather than in isolation. The same logic applies to bathing and toileting aids. A shower chair, grab bars, and raised toilet seats create a practical pathway to safe personal care routines, reinforcing safe transfer techniques, balance strategies, and the immediate reductions in fall risk. By integrating these aids into practice sessions, therapists can tailor interventions to the patient’s living environment, reducing the gap between clinic performance and home competence.

Cognitive task boards and activity kits broaden the scope of functional training beyond motor skills to executive function and attention. A board that requires sorting, sequencing, or categorization can help a person practice planning and problem solving in a context that resembles everyday choices—what to wear for the day, how to organize a simple shopping list, or how to manage a small household budget. The value lies not only in the completed task but in the process: anticipating steps, monitoring progress, adjusting strategies, and maintaining focus until a goal is reached. This approach aligns closely with the principle of contextual relevance, a central tenet of occupational therapy. When exercises resemble real-life tasks, motivation intensifies, skill transfer improves, and therapy sessions yield tangible gains that patients notice in their routines at home, at work, or in the community.

In clinical environments, the layout and selection of functional task training equipment are deliberate. An OT room designed for purposeful, activity-based interventions often features functional simulation zones—kitchens and bathrooms that host a range of adaptive equipment and safe, task-specific challenges. There is a deliberate emphasis on safety and accessibility: non-slip flooring, rounded edges on furniture, and a clear path for mobility aids. The equipment is chosen not merely for its novelty but for its alignment with therapeutic goals and the patient’s living context. Therapists observe performance across multiple dimensions—strength, coordination, coordination of vision and hand, safety awareness, and task initiation—while guiding patients through adjustments to technique, pace, and strategy. The aim is to cultivate a sense of mastery rather than dependency; the patient learns to decide when to use a particular tool and how to integrate it seamlessly into daily routines.

The experience of using functional task training equipment is often collaborative. Therapists calibrate the apparatus to the patient’s size, weight-bearing capacity, and cognitive load. Customization matters because growth and aging alter what a person can achieve with a given tool. For children, equipment must be adaptable to changing hands and evolving goals; for adults recovering from stroke or orthopedic injuries, devices must accommodate residual weakness, pain levels, and fatigue patterns, while promoting progressive challenge. This individualized approach rests on a careful assessment framework and ongoing re-evaluation, ensuring that the tools used remain aligned with current needs and functional outcomes. When a patient practices the same sequence repeatedly with variations in complexity, the therapy builds a robust mental and motor map that travels beyond the clinic walls into everyday life.

Beyond functional gain, the use of these tools also advances safety and confidence. Structured practice with dressing trainers or adaptive utensils creates a safe space to learn fall-prevention habits, safe handling of objects, and the sequencing required to complete self-care tasks. Confidence grows as the patient experiences success across a continuum—from simple, repetitive actions to more complex, multi-step activities. In turn, reduced caregiver dependence and improved quality of life often follow. Research in occupational therapy consistently shows that structured, task-focused practice leads to meaningful improvements in ADLs and IADLs, especially when it is guided by clear goals and adapted to patient preferences and home environments. The therapeutic narrative becomes a story of regained agency: the patient takes charge of small decisions, feels the competence that comes with capability, and notices how these changes multiply across daily obligations, social participation, and personal identity.

A crucial element in the efficacy of functional task training equipment lies in the disciplined use under professional guidance. Timing and dosing matter; progress should be measured not only by task completion but by the smoothness of the process, the reduction in compensatory movements, and the patient’s ability to anticipate and prevent errors. Proper sizing and customization support comfort, which in turn sustains engagement. Therapists work with patients and families to adapt home environments, ensuring the equipment translates beyond the clinic. A well-designed home exercise plan built around real-life tasks reinforces consistency and continuity of care, amplifying the therapeutic return on investment. In this sense, equipment is not a static portfolio of devices but an evolving toolkit that grows with the patient’s abilities and living situation.

Interventions that emphasize functional task training equipment also stress the importance of collaboration with other health professionals and caregivers. The goal is not to replace human support but to extend it with practical, reliable strategies that promote independence. Therapists may consult with occupational therapy assistants, nurses, or social workers to modify tasks, adapt environmental features, and align goals with community resources. This collaborative ecosystem strengthens the patient’s social participation, a critical dimension of well-being. As people age or experience chronic conditions, maintaining autonomy becomes a dynamic pursuit, attended by teamwork, ongoing assessment, and an adaptable set of tools that respond to shifting needs.

The real-world value of this equipment is perhaps best illustrated by its ability to bridge the gap between restoration and participation. A patient who can dress, feed, groom, and prepare meals with minimal assistance can re-enter daily life with renewed purpose. They can engage in hobbies, maintain employment or volunteer roles, and connect with family in meaningful ways. This bridge—from impairment-focused therapy to community involvement—defines the broader impact of functional task training equipment. It is a reminder that the purpose of OT supplies extends far beyond the clinic: they enable people to claim their place in daily life with dignity and resilience.

For practitioners seeking practical grounding, a broad understanding of the catalog of tools and how they fit together is essential. The continuum from dressing aids to cognitive task boards requires a nuanced appreciation of each device’s role, its limitations, and the scenarios in which it will be most effective. An essential takeaway is that the value of these tools lies in their thoughtful integration into a patient-centered plan. The aim is not to overwhelm with options but to curate a suite of capabilities that can be staged, rotated, and scaled as the patient progresses. This approach preserves motivation, sustains engagement, and helps ensure that skill gains endure once a patient returns to the rhythms of home life.

In sum, functional task training equipment embodies the essence of occupational therapy: translating capacity into independence through purposeful activity. It is through these tools that therapists turn the daily routines of living—dressing, eating, bathing, cooking, managing money, and organizing spaces—into actionable, repeatable, and meaningful activities. The result is not merely improved function; it is a rebuilt sense of self, a recalibrated relationship with daily life, and a renewed capacity to participate with confidence in the communities that matter most. For clinicians, patients, and families alike, this is the core promise of OT therapy supplies: a practical pathway from rehabilitation to real-life resilience.

For further exploration of the practical tools and equipment that support occupational therapy practice, see the resource on tools and equipment for occupational therapists. This guide offers insights into selecting, adapting, and sequencing items to match therapeutic goals and home contexts. tools and equipment for occupational therapists

External resource for further reading: American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) provides authoritative guidelines and evidence-based practice resources that underpin functional task training and the broader OT framework. https://www.aota.org

Wired for Focus: How Cognitive and Sensory Tools Translate OT Therapy Supplies into Daily Function

Cognitive and sensory integration tools occupy a vital crossroad in occupational therapy supplies. They do more than spark curiosity or calm nerves; they tune attention, support executive function, and bridge perception with purposeful action in daily life. When a child with sensory processing differences or a adult recovering from a neurological injury engages with these tools, therapists are not simply providing stimulation. They are guiding the nervous system toward better organization, more intentional responses, and, crucially, greater independence. In this sense, cognitive and sensory tools are not add-ons but core components of a holistic treatment plan that links the brain’s processing philosophies with the hands’ capacity to enact meaningful activities.

The materials a therapist selects for this work reflect a careful alignment with theoretical principles and practical realities. Among sensory integration aids, weighted blankets offer deep pressure input that can modulate arousal and promote calm. The sensation of steady, controlled pressure helps the nervous system estimate posterior strength and organize sensory inputs, which in turn can improve sleep, attention, and emotional regulation. Textured sensory boards present varied tactile textures, inviting graded discrimination and fine motor control while challenging the brain to integrate touch with motor planning. Vibration toys and sensory bins, meanwhile, engage multiple modalities—tactile, proprioceptive, and kinesthetic—creating a multisensory playground in which neural pathways can be strengthened through purposeful exploration. Taken together, these tools help individuals build a repertoire of self-regulation strategies that they can adapt beyond the therapy room.

Yet cognitive support tools deserve special emphasis because they target the attention-and-execution pathway that underpins almost every activity. Structured, science-based activities such as those found in certain sensory sticks provide predictable, repeatable brain breaks. The idea is simple but powerful: short intervals of focused work followed by a framed sensory reset can restore cognitive stamina, reduce distractibility, and improve task persistence. Sensory chew necklaces offer a controlled outlet for oral sensory input, addressing self-regulation needs for some individuals who seek oral sensory feedback as a regulator. These items are not distractions; when embedded within a thoughtfully designed plan, they become supportive cues that help a person stay oriented to the task at hand.

What makes these tools particularly valuable is their compatibility with a broader therapeutic strategy rather than their standalone effects. An experienced occupational therapist tailors tool selection to the patient’s unique profile, sizing and customizing implements for age, motor ability, sensory thresholds, and cognitive load. This individualized approach is essential because the same tool can have very different implications for two people. For a young child with heightened sensory seeking, a textured board may support tactile exploration and fine motor development; for an adult navigating post-stroke recovery, weighted input might help regulate stress responses during tasks that demand concentration and sequencing. The key is to embed these tools within a purposeful, activity-based framework so that every interaction translates into meaningful function—whether it is dressing, writing, or preparing a simple meal.

Within the therapy room, this philosophy translates into environments that are structured yet flexible. A well-designed OT room offers functional simulation zones that mirror real-life settings—a kitchen area for meal preparation, a bathroom for self-care tasks, and craft or woodwork stations that promote hand strength and coordination. The same principle applies to the selection of cognitive and sensory tools: they should be integrated into these zones so that practice is not abstract but directly transferable to daily life. In this sense, the room becomes a bridge between theoretical concepts of sensory processing and practical competencies such as buttoning a shirt, tying shoelaces, or organizing a workstation. Even the safety features of the environment matter; non-slip flooring and furniture with rounded edges reduce the risk of injury during dynamic tasks, ensuring that the focus remains on learning and functional gains rather than on safety concerns.

The effectiveness of cognitive and sensory integration tools hinges on deliberate, ongoing assessment and adjustment. It is not enough to introduce a weighted blanket or a sensory stick; the therapist must observe how the individual responds, how sustained attention shifts across sessions, and how self-regulation changes across contexts. Regular re-evaluation ensures that tools remain appropriately challenging and that progression reflects real-world functional gains. This is especially important for growing children, whose needs evolve as motor and cognitive skills mature. Proper sizing, adaptation, and progression are not cosmetic details; they determine whether a tool helps a person move toward independence or simply introduces new avenues for dependency. In practice, this means that the plan evolves hand in hand with the person’s development, with tools scaled to current abilities and gradually stretched as competence increases.

For families and clinicians alike, the appeal of cognitive and sensory tools lies in their versatility and ecological relevance. They support a spectrum of conditions, from attention regulation in neurodevelopmental disorders to post-injury cognitive rehabilitation. In ASD and ADHD, for example, structured brain breaks and regulated sensory input can mitigate overload and support sustained engagement in learning activities. In neurological populations, the same tools can aid fatigue management and task sequencing by providing reliable cues that help the brain map perception to action. The overarching aim remains consistent: to foster independence in daily activities by enhancing the brain’s ability to process, organize, and apply information in real time. When these elements align, a child can transition from fumbling through dressing to performing the steps with confidence, or an adult can prepare a meal with fewer prompts and greater self-reliance.

This integrative approach is not merely theoretical. A growing body of practice-based evidence supports the idea that combining sensory and cognitive strategies with functional tasks yields meaningful improvements in daily living skills. The evidence underscores that success depends on consistent use under professional guidance, sensible customization, and a clear linkage between therapy activities and real-world tasks. In other words, the tools themselves are catalysts, but their power is realized only when they are embedded in a comprehensive plan that respects the person’s goals, environment, and daily routines. The occupational therapist, therefore, becomes both a designer of activity systems and a coach for self-regulation, helping clients translate the quiet work of sensory modulation and cognitive pacing into the loud clarity of independent living.

The broader implications extend beyond the therapy room. When cognitive and sensory principles are woven into everyday routines, families encounter less reliance on caregivers and more capacity for participation in once-challenging activities. In this sense, the chapter on cognitive and sensory integration tools becomes a chapter about autonomy. It explains why therapists curate a dynamic toolkit rather than a fixed inventory, and why the success of an OT program often hinges on the patient’s ability to apply a simple strategy—breathing, pausing, or a sensory cue—at the moment a task becomes demanding. The readiness to generalize learned skills to home, school, and community settings is the true measure of progress and a signal that therapy has translated from a controlled environment to the texture of everyday life.

For those exploring targeted pathways within autism-specific interventions or looking for deeper evidence that guides practice, an accessible exploration of related approaches can be found in resources dedicated to autism-focused occupational therapy strategies. See this discussion on occupational therapy for autism for a focused lens on how sensory integration approaches are tailored to autistic individuals and families, including practical considerations for home and school settings: occupational therapy for autism.

As the field advances, there is growing recognition that the most effective OT therapy supplies are those that respect the complexity of human sensation and cognition while staying firmly anchored in real-world function. The ongoing collaboration between therapists, patients, and families helps ensure that cognitive and sensory tools remain responsive to changing needs and goals. This collaborative orientation matters, because the tools themselves are only as good as the plans that shape their use. When the plan aligns with daily demands, and the tools are applied with fidelity, the result is a tangible shift in independence, confidence, and the quality of life for people navigating the path from impairment toward participation.

For clinicians seeking broader insights into the standards, performance, and practical applications of therapy equipment, the literature and professional resources offer a robust foundation for informed decision-making. A comprehensive resource with evidence-based guidance on equipment standards and practical applications can be explored at the following external reference: https://www.therapyequipment.com/blog/occupational-therapy-equipment-standards-performance-applications. This external source provides a deeper dive into how equipment design supports safety, efficacy, and outcomes across diverse therapeutic contexts, complementing the clinical reasoning that guides tool selection and progression in practice.

Foundations of Comfort and Function: Seating and Positioning as the Quiet Engine of OT Therapy Supplies

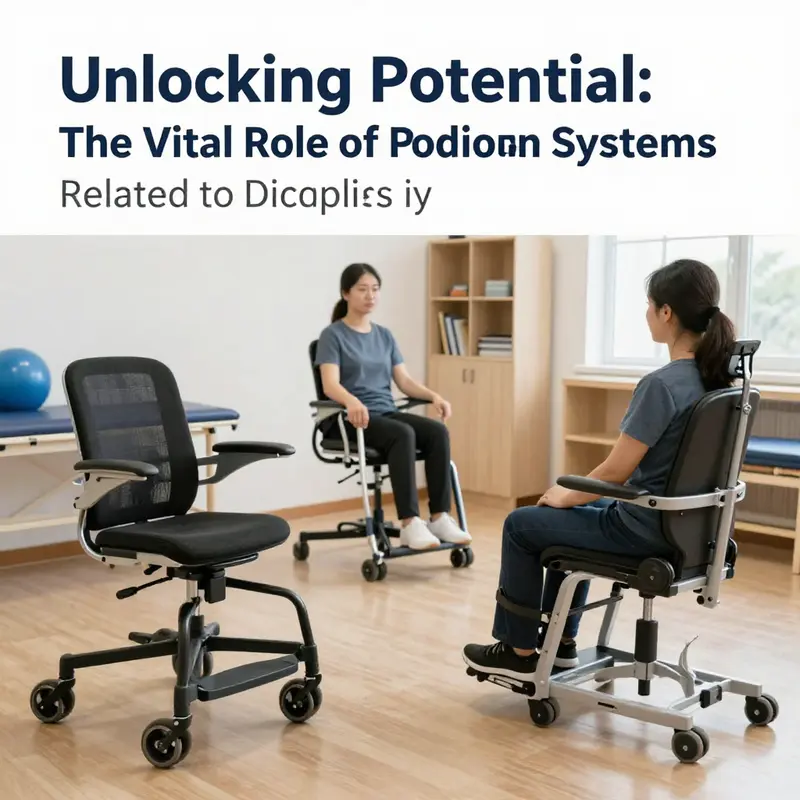

Seating and positioning are not flashy features in an OT clinic, yet they form the quiet engine that empowers every moment of daily life. When a person sits with stability, protection, and appropriate alignment, the body can attend, communicate, eat, write, and engage with others. Occupational therapy supplies devoted to seating and positioning are more than cushions or frames; they are a carefully chosen toolkit designed to optimize comfort, safety, and participation. This chapter traces how posture connects to function, showing how adaptive seating systems, positioning supports, and sensory and environmental considerations come together in a client-centered intervention model. The aim is not merely to hold someone upright but to enable authentic occupations—the routines that define a person’s day and identity.

At the core of seating and positioning is a simple principle: gravity and movement interact with the body, and misalignment or undue pressure can cause fatigue, pain, and reduced motor control. OT practitioners view seating as a dynamic process that addresses trunk stability, pelvic alignment, neck and head posture, and limb position. An adaptive seating system typically features adjustable backrests, lateral supports, and pelvic belts that stabilize the trunk while preserving a comfortable range of motion for reaching, writing, and operating devices. The emphasis is on modifying the environment to support the body’s natural capabilities rather than forcing a one-size-fits-all frame. This is where OT supplies become living tools: cushions with contours, modular back supports, and soft fasteners that can be reconfigured as needs evolve.

Positioning pillows play a critical role: they provide targeted support to the sacral area, hips, and knees to keep joints in neutral positions and distribute pressure. For individuals with sensory processing differences or motor tone challenges, these pillows can contribute to comfort and calm, reducing fidgeting and enabling sustained engagement in tasks such as handwriting or computer work. For children, pediatric positioning products are designed with growth in mind, accommodating changes in posture as a child develops. The goal is not only to keep a child upright but to create a supportive base that fosters exploration, social participation, and safe interaction with peers.

The range of OT seating and positioning tools extends beyond the chair and cushion. Pediatric walkers and gait trainers, for example, support mobility while maintaining alignment during ambulation practice. These devices promote upright posture, pelvis stabilization, and trunk control as a client takes steps in therapy. When combined with a sensory integration approach, gait training can become a multisensory activity that invites curiosity and confidence, rather than fear of falling. Therapy swings provide controlled, safe movement that can promote vestibular engagement, proprioceptive feedback, and trunk strengthening. They are not mere outlets for play; they are deliberate tools for shaping movement patterns and postural awareness that translate to daily activities such as dressing, eating at a table, or participating in school routines.

Interactive developmental toys and task-specific seating aids also contribute to positioning in meaningful ways. Toys and activities that require precise hand-eye coordination reinforce the need for stable seating: a child who can maintain an upright posture while manipulating a toy demonstrates endurance for longer school tasks, arts and crafts, or chores at home. In adult rehabilitation, similar principles apply when performing tasks like knitting, cooking, or sorting cards—activities that demand a steady seat, core stability, and accessible arm reach. In all cases, the OT room becomes a living laboratory where the person learns to coordinate body, tools, and environment toward functional independence.

The clinical setting itself reflects the importance of safe, functional seating. Rooms are designed with flexible, soft surfaces and carefully engineered layouts that support multiple seating arrangements. The floor surface is often non-slip, and furniture edges are rounded to prevent injury during transitions or accidental bumps in a session. A deliberate emphasis on safety enhances confidence, allowing clients to explore new movement strategies and task demands. When therapists guide a client through kitchen simulations, seating and positioning are foundational. A stable, adjustable chair or stool permits the client to bring the work surface within reach, align the forearms with the task, and execute multi-step actions without unnecessary strain. The result is a more natural, integrated practice where technique becomes habit, and habit translates into everyday competence.

The evidence base behind these choices highlights several interlocking themes. First, consistent, guided use of seating and positioning interventions leads to measurable gains in functional independence. Second, proper sizing and customization are essential, particularly for growing children or individuals undergoing changes in posture due to illness or injury. Third, an occupation-based approach—one that centers the client’s goals, daily routines, and personal values—drives better engagement and satisfaction with therapy. In practice, a therapist collaborates closely with clients and families to identify preferred activities, everyday challenges, and safety concerns, then selects seating components and supports that align with those realities. This approach ensures therapy remains relevant, motivating, and capable of improving participation in real-world contexts rather than merely achieving superficial postural alignment.

An important framework shaping practice in seating and positioning is the adoption of standards that guide the selection, placement, and fixation of flexible postural supports. For professionals working across clinical settings, ISO/TS 16840-15:2024 provides essential guidance on balancing postural control with comfort and safety. The standard emphasizes soft, adaptable supports that accommodate dynamic needs while cautioning against rigid materials in seating. By prioritizing soft, flexible supports, therapists can support safe seating without compromising mobility, pressure distribution, or comfort. This standard also helps practitioners navigate the trade-offs between stability and participation, ensuring seating configurations support, rather than restrict, meaningful activity. As with all standards, the aim is to translate technical requirements into practical, person-centered care that respects the client’s autonomy and dignity. Clinicians align device choices with a comprehensive assessment of posture, movement patterns, sensory needs, and the specific tasks the person seeks to perform.

Incorporating seating and positioning into OT therapy supplies also means considering the environments in which clients live, learn, work, and socialize. An occupation-based approach recognizes that a chair in a classroom, a chair at home, and a seating system in a clinic all influence a person’s ability to participate. Therapists assess how seating affects tasks such as dressing, grooming, meal preparation, or computer use and then tailor equipment to the setting. This alignment with daily life is essential for lasting outcomes and supporting productive aging. It also underscores the value of environmental modification as a complement to direct seating interventions. Grab bars, shower chairs, adaptive stools, and supported seating options can reduce barriers to independence at home, empower safe transitions in the community, and ease the burden of caretaking. The interconnection between seating systems and broader environmental supports reinforces the OT’s role in promoting autonomy through thoughtful equipment selection, precise fitting, and ongoing adjustments as needs evolve.

To translate these concepts into everyday practice, therapists increasingly rely on a spectrum of training resources and equipment catalogs that emphasize evidence-based, person-centered decision making. The selection process begins with a comprehensive evaluation: analyzing trunk control, pelvic alignment, leg positioning, and the client’s tolerance for different postures during functional tasks. The therapist then considers the sequence of tasks the client aims to master, the time required to complete them, and the environmental constraints of the setting. The ultimate objective is to create a seating and positioning plan that reduces pain, improves endurance, facilitates engagement in preferred activities, and enables safer participation in daily routines. In this way, seating and positioning become a bridge between the body’s needs and the activities that give life meaning.

For readers seeking practical guidance beyond theory, resources such as Tools and equipment for occupational therapists offer an accessible overview of seating solutions and supports that therapists integrate into treatment plans. This collection helps clinicians select appropriate seating configurations, cushions, back supports, and posture aids to fit individual profiles. It also supports families and caregivers in understanding how to adjust seating at home as children grow or as patients recover. The linked resource provides a valuable starting point for navigating practicalities of implementation while keeping a person-centered focus.

In sum, seating and positioning are the quiet but indispensable backbone of OT therapy supplies. They enable reliable participation in meaningful activities by providing a foundation of postural support, pressure distribution, and movement freedom. They encourage a holistic, occupation-based approach that respects each client’s goals, preferences, and daily rhythms. Through careful assessment, thoughtful selection, and ongoing refinement, seating systems become adaptive partners in rehabilitation and everyday life—supporting independence, safety, and quality of life across clinical settings and home environments. For practitioners and families alike, the message is clear: when seating and positioning are right, the whole day becomes more accessible, more comfortable, and more true to the person’s priorities.

External resource: ISO/TS 16840-15:2024 standard provides the technical framework for seating supports and postural management. See the official ISO document for details: https://www.iso.org/standard/97532.html

Blueprints for Independence: Environmental Modification in OT Therapy Supplies

Environmental modification is not a single device or a flashy gadget; it is a structured practice that reshapes a person’s daily landscape so meaningful activities become accessible again. In occupational therapy, the goal is to expand a client’s participation in life roles by aligning the physical environment with what a person can do today and what they can grow toward tomorrow. This alignment rests on careful assessment, thoughtful selection of modifications, and a steadfast attention to safety, dignity, and sustainability. When a room is thoughtfully adapted, a patient may move from dependency toward autonomy with a transition that feels less like therapy and more like a remaking of daily life itself. The work centers on transforming risks into opportunities—turning a barrier into a lever that amplifies capability, confidence, and engagement in everyday activities such as bathing, dressing, cooking, and moving about the home.

Assessment sits at the heart of environmental modification. Therapists begin with a holistic view of the person and their environment, watching how tasks unfold in the contexts that matter most. They observe the rhythm of shared routines, the friction points that slow or derail independence, and the emotional weight of navigating change. This process is not merely about fitting a device to a problem; it is about choosing changes that amplify participation in meaningful activities. Simple lever handles instead of round knobs can transform opening a cabinet or turning a faucet from a strenuous trial into a seamless moment of agency for someone with arthritis or limited grip strength. The assessment also weighs the home’s architecture, the layout of rooms, and the potential risks that a single obstacle can pose for safety. In some cases, a shower chair or a roll-in shower becomes a prerequisite for safe hygiene. In others, widening a doorway or lowering a countertop may unlock a kitchen zone that had been out of reach. The guiding principle remains constant: modifications should be tailored, functional, and proportionate to the client’s abilities and goals, with a clear plan for ongoing evaluation as needs evolve.

Within the broader spectrum of environmental modification, there are two overarching categories that reflect both the complexity of the task and the breadth of outcomes sought. Simple modifications include grab bars, non-slip mats, lever handles, and raised switches or buttons that reduce the precision of grip or dexterity required. These adaptations are frequently feasible, cost-effective, and quick to implement, making a tangible difference in a short time frame. Complex modifications address more persistent or severe limitations and often involve integrated modifications that touch multiple functional domains. Wheelchair ramps, bathroom lifts, and smart-home technologies that automate lighting, climate control, or door operation exemplify this category. They require careful planning, sometimes funding coordination, and collaboration with builders or facilities teams to ensure that installations meet safety standards and local codes. The aim of both simple and complex modifications is identical: to lower barriers while preserving the client’s sense of autonomy, control, and identity within the home’s everyday spaces.

A foundational concern in environmental modification is safety without sacrifice. Therapists design and implement changes with attention to fall risk, reach, and balance. Floors with non-slip properties, rounded edges on furniture, and stable surfaces become foundational choices in both clinical and home environments. The deliberate selection of materials and finishes can influence confidence as much as concrete capabilities. A thoughtfully configured kitchen or bathroom can become a stage for purposeful practice—where clients rehearse dressing, meal preparation, and personal care in settings crafted to mirror real life while minimizing risk. In hospital-based OT rooms, these principles translate into functional simulation zones: a kitchen area that replicates real meal prep, a bathroom mock-up for bathing routines, and craft or manual workstations that support hand function and spatial organization. These zones enable purposeful, activity-based interventions that tie directly to a client’s home life, bridging the gap between laboratory improvements and practical daily function.

The types of environmental modifications reveal a spectrum from low-tech to tech-enabled solutions. Simple modifications often deliver the largest, quickest impact in a resource-conscious manner. Grab bars placed at strategic heights, non-slip mats in showers, and lever-style door handles can dramatically improve safety and ease of use. For a person who struggles with reaching or twisting the wrist, a lever faucet or pull-down shower head may replace a vulnerable, high-friction action with a smooth, controlled motion. More complex modifications, while requiring careful coordination, carry the promise of greater independence across a broader range of tasks. Ramps and widened entryways transform mobility within and between spaces, while bathroom lifts and adjustable-height counters create new possibilities for independent self-care. The inclusion of smart home technologies marks an emergent frontier: automated lighting that responds to motion, voice-activated assistants that control appliances, and sensors that monitor safety without intruding on privacy. These technologies can support decision-making, reduce fatigue, and provide ambient structure that guides daily routines. The selection of environmental modifications, whether simple or complex, should always align with the client’s life goals, the home’s architectural reality, and the resources that can support sustainable use over time.

Sustainability and equity have risen to the forefront of environmental modification conversations. A growing critical lens examines not only whether a modification works, but whether it is affordable, maintainable, and accessible to people across socioeconomic contexts. Therapists increasingly consider the lifecycle of a modification: upfront costs, durability, ease of cleaning, and potential for adaptation as a person’s needs shift. A recent focus on sustainable practice asks how we can minimize environmental impact without compromising safety or function. This includes selecting materials with low environmental footprints, designing for longevity, and exploring funding models that reduce inequities in access to home adaptations. The literature notes that while clinicians recognize the importance of sustainability, financial constraints and unequal access often limit implementation. The implication is clear: there is a need for affordable, eco-friendly solutions and systemic support that ensure every client, regardless of means, can experience independence in their living environment. This is not merely a matter of expense; it is a matter of opportunity and dignity, enabling people to remain at home, in familiar surroundings, with the support they need to participate in daily life.

In practice, environmental modification connects directly to outcomes familiar to OT teams across settings. Initial gains in function frequently translate into reduced caregiver burden and enhanced quality of life. When a patient can bathe independently, prepare a simple meal, or dress with fewer prompts, confidence grows and participation expands beyond the task itself. The gains extend to social participation, mental well-being, and a sense of self-efficacy that empowers continued practice and engagement. This is where the environmental modifications discussed in clinical rooms begin to reverberate in the home, workplace, and community. Therapists recognize that the home is not just a place of residence; it is a therapeutic environment in which the right adaptations can sustain gains, prevent regression, and anchor meaningful daily routines.

Real-world application in settings such as OT rooms within rehabilitation hospitals demonstrates how these principles play out in concrete ways. Functional simulation zones mimic real life, allowing clients to rehearse dressing, cooking, or personal care with modifications that reflect what they will face after discharge. The alignment of space design with safety standards—non-slip flooring, rounded edges, accessible pathways—serves not only to protect clients during therapy but to promote confidence in their eventual return to independent living. The emphasis on assessment-driven customization ensures that each modification serves the person, not the device. When therapists document progress and revisit plan adjustments, the modifications evolve with the client, accommodating improvements or new limitations as rehabilitation progresses.

Embedded within this approach is a continuous thread of collaboration and education. Therapists partner with families, caregivers, and, when appropriate, builders or facility managers to implement modifications that endure. The process is iterative: assess, modify, reassess, and refine. It is also culturally sensitive, recognizing that home environments, daily routines, and personal preferences vary widely. The most successful environmental modifications honor the client’s values and routines, while introducing changes that expand possibilities rather than impose constraints. In this sense, environmental modification is a form of landscape architecture for daily living—carefully drawn, negotiated, and enacted to support a life that remains deeply personal and profoundly capable.

For readers seeking deeper exploration of sustainability and equity in home modifications, several lines of thought are especially fruitful. The literature calls for more research into cost-effective, scalable solutions and the development of funding pathways that reduce disparities in access to adaptations. It also urges ongoing dialogue about how environmental modifications interact with broader care networks, housing policy, and community resources. In practice, clinicians continually translate these insights into patient-centered plans that respect both resource realities and the imperative of enabling independent living. This is not simply about installing devices; it is about designing a life-world where daily activities are within reach, where risks are mitigated without eroding autonomy, and where the client’s voice remains central in every decision.

In summation, environmental modification products in OT therapy supplies function as strategic tools in an integrated approach to rehabilitation. They exemplify how environmental engineering, clinical reasoning, and compassionate care converge to restore independence. When used thoughtfully, these adaptations enable people to reimagine what is possible in their own homes and communities, turning the unfamiliar into a familiar rhythm of daily life. The journey from assessment to implementation to ongoing evaluation reflects a profession relentlessly focused on participation, safety, and the dignity of choice. For practitioners, families, and policymakers, the message is clear: with deliberate design and equitable access, environmental modification can transform not just spaces, but lives, one adapted room at a time. For those who wish to explore this topic further, adaptive environment strategies are a practical doorway to understanding how occupational therapy supports meaningful, sustainable independence in real-world settings.

Final thoughts

The integration of OT therapy supplies in rehabilitation not only enhances the functional independence of patients but also equips business owners in the healthcare sector to offer comprehensive care. By understanding the various categories of supplies, from fine motor tools to environmental modifications, businesses can tailor their offerings to meet the unique needs of their clients. Investing in quality OT materials ultimately leads to improved patient outcomes and satisfaction, reinforcing the vital role of these supplies in therapeutic success.