Occupational therapy is pivotal in the recovery journey of stroke survivors, focusing on both physical rehabilitation and emotional well-being. As business owners in the healthcare or wellness sphere, understanding how targeted exercises can aid stroke recovery is crucial to improving patient outcomes and satisfaction. This article delves into occupational therapy practices that address upper limb function, gait training, innovative technologies, and mental health considerations, providing a holistic view of rehabilitation that aligns with best practices for patient care.

null

null

Walking Together Again: Gait Rehabilitation as a Pathway to Independence in Occupational Therapy After Stroke

Gait rehabilitation in occupational therapy is more than a sequence of movement drills. It is a carefully woven process that links the mechanics of walking with the daily rituals of living. For people recovering from a stroke, regaining a stable, efficient gait means reclaiming independence in activities as diverse as crossing a street, navigating a crowded grocery aisle, or keeping up with family during a weekend outing. The rehabilitation journey centers on the belief that walking is not merely a physical action; it is a structured series of decisions that require balance, strength, perception, and confidence. In OT practice, gait training is thus framed as an integrative enterprise. It starts with understanding each patient’s unique pattern of weakness and spasticity, then moves toward restoring coordinated movements that permit safe, purposeful ambulation in real-world settings. The approach rests on a triad: restitutive motor re-education, compensatory strategies to bridge current limitations, and a robust emphasis on the mental and emotional anchors of recovery. The literature that guides clinicians in this work points to a spectrum of techniques that, when combined thoughtfully, can recalibrate walking from a disabling symptom into a functional, meaningful activity.

At the core of gait rehabilitation are foundational neurorehabilitation principles that have guided stroke recovery for decades. Neurodevelopmental techniques (NDT) remain a cornerstone because they emphasize re-establishing normal movement patterns rather than simply teaching a sequence of steps. NDT invites clinicians to observe the patient’s spontaneous motor choices, then shape practice to promote smooth transitions between movement components. The objective is not to force a perfect stride but to cultivate a more natural repertoire of movements that the patient can rely on in daily life. This emphasis on reproducible, functional patterns helps patients regain control over the rhythm of their walk, which in turn nurtures confidence and reduces fear of falling. As therapists apply NDT, they remain attuned to subtle signs of compensatory strategy use. By guiding the patient toward more efficient weight shifting, knee and ankle alignment, and pelvic control, therapists lay the groundwork for more advanced gait tasks.

Yet gait is not a one-size-fits-all enterprise. Strengthening the muscles of the lower limb is a critical parallel track. Targeted resistance work addresses weak hip abductors, knee extensors, and ankle dorsiflexors that often falter after a stroke. The aim is to build a reliable foundation for the stance phase, stabilize the pelvis, and improve stance-to-swing transitions. Practitioners tailor these strengthening activities to the patient’s stage of recovery and to the specific deficits observed during gait assessment. The information gathered during evaluation guides progressive loading and safe progression to more challenging tasks. Strength gains alone do not guarantee better walking, but when paired with precise timing and coordination work, they enable larger strides, steadier balance, and faster walking speeds. The careful progression from low-demand to higher-demand tasks mirrors the patient’s evolving capabilities and maintains engagement by aligning effort with meaningful goals.

A hallmark of modern gait rehabilitation is the use of partial body weight–supported treadmill training. This modality creates a controlled environment where patients practice stepping with rhythmic, repetitive motion while the therapist monitors posture, foot placement, and limb symmetry. The weight support reduces the fear of collapse and allows more confident practice of gait patterns that may be unstable in overground walking. As therapists increase the body weight support in measured steps, patients expose themselves to longer, more consistent practice bouts that build endurance. Treadmill training also offers the advantage of objective metrics: gait speed, symmetry, and cadence can be tracked over time, providing a tangible frame for goal setting and progression. When integrated with NDT and strengthening work, treadmill training becomes a pivotal bridge between rehabilitation sessions and real-world ambulation.

But walking in the clinic must translate to walking outside of it. Task-specific training anchors gait practice in real-world contexts that demand balance, perception, and problem-solving. Therapists design tasks that resemble everyday challenges: negotiating obstacle courses, placing the foot on uneven surfaces, or coordinating steps in a narrow space. The emphasis is less on rote repetition and more on functional adaptability. Patients learn to anticipate changes in terrain, adjust speed, and modulate force with each step. This approach mirrors the cognitive demands of community ambulation, where decisions are made in the presence of distractions, sensory inputs, and changing environmental cues. Through task-specific practice, patients begin to integrate motor skills with cognition, attention, and judgment—the cognitive-motor fusion that ultimately supports safe, independent mobility.

These four strands—NDT, targeted strengthening, partial body weight–supported treadmill training, and task-specific real-world practice—form a cohesive portfolio that clinicians tailor to each patient. A 2024 synthesis by Teodoro champions a functional, goal-oriented framework that situates gait training within complex environments. The core message is clear: improvements in biomechanics must be inseparable from improvements in how a person navigates real life. Elucidating this, Teodoro underscores the value of designing environments that challenge balance and coordination while still providing a therapeutic scaffold. The implication for practice is pragmatic: gait rehabilitation should not stay confined to a straight path on a treadmill or a flat hallway. Instead, it should unfold through routes that mimic daily life, from stair negotiation to crossing crowded rooms, and through tasks that require the patient to adapt to ever-changing demands. When therapy blends purposeful task selection with rigorous repetition, patients experience meaningful gains in speed, stability, and, crucially, independence.

The long arc of evidence supporting this approach rests on a foundation of intensive, repetitive practice and individualized planning. A systematic synthesis from Eng in 2007 emphasizes that the dosage and structure of practice matter as much as the content itself. Patients who engage in high-intensity, repetitive gait practice across sessions tend to achieve more durable improvements in walking endurance and speed. The takeaway for clinicians is a prescription-like confidence in personalizing regimens: what works best for one patient may not suffice for another. The most effective programs are those that actively adapt to the patient’s evolving capabilities, constraints, and goals. They are anchored in careful assessment, ongoing feedback, and a transparent, patient-centered communication loop that keeps the patient engaged and motivated through setbacks and plateaus alike.

The clinical landscape is further enriched by broader considerations that surround gait rehabilitation. The stroke recovery journey is not purely a mechanical restoration; it demands attention to mental health, motivation, and emotional resilience. A recent study indicates that while many OT practitioners regard mental health as a priority, a substantial portion feel inadequately supported to address it comprehensively. This gap matters for gait rehabilitation because walking practice can provoke anxiety about balance, fear of falling, or concerns about social participation. Addressing mental health alongside physical recovery creates a more resilient walking system. When therapists integrate strategies that support mood, confidence, and goal pursuit, patients are more likely to persist with challenging gait tasks and to translate gains from the clinic to community life. In practice, this means pairing movement-focused sessions with brief coaching on coping strategies, reinforcing autonomy, and validating the patient’s lived experiences of recovery. The link between motor recovery and psychological well-being is not incidental; it is a synergistic relationship that shapes outcomes and the patient’s sense of capability.

Looking ahead, gait rehabilitation continues to expand through explorations of adjunctive therapies and evolving measurement tools. The chapter of stroke recovery wades into new territory with the exploration of electrical stimulation approaches that aim to prime brain plasticity while patients practice walking. Although still emerging, such modalities—carefully integrated with conventional gait training—offer a glimpse of how neurostimulation might amplify motor learning. The hope is not to replace established practice but to augment it, creating a richer, more dynamic training environment that supports both limb function and neural reorganization. In ischemic stroke, where blocked vessels have disrupted blood flow and neural networks, harnessing multiple avenues of recovery may yield greater gains in upper limb mobility and walking safety. Nevertheless, these techniques require rigorous evaluation, careful patient selection, and close monitoring to ensure safety and to clarify who stands to benefit most.

Within this evolving framework, practitioners also rely on practical resources that distill the core ideas into actionable steps. One accessible pathway is to explore a concise, technique-focused overview that distills the most commonly used methods in occupational therapy. Readers can engage with a survey of methods through an overview article titled Techniques used in occupational therapy, which offers a compact guide to the repertoire that therapists draw from in gait and mobility rehab. techniques used in occupational therapy serves as a useful reminder that the field rests on a diverse toolkit, ranging from sensory integration and motor learning principles to task adaptation and environmental modification. This resource does not replace the need for individualized assessment but can illuminate the shared vocabulary therapists use to describe progress and to collaborate with patients and families.

For clinicians who want a broader evidence-based frame, current literature points to the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy as a reliable home for contemporary gait rehabilitation trends. The article Current Trends in Gait Rehabilitation for Stroke Survivors synthesizes practical guidance on how gait training evolves in clinical practice, emphasizing functional outcomes, environmental complexity, and the cognitive-motor integration that supports safe community ambulation. Practitioners who read this article gain a lens on how the field is moving toward more holistic, context-rich training. The link below directs readers to the 2024 analysis, which consolidates recent findings and translates them into strategies for daily practice. External resource: https://journals.lww.com/jnpt/Abstract/2024/01000/CurrentTrendsinGaitRehabilitationforStroke.1.aspx

In sum, gait rehabilitation in occupational therapy emerges as a dynamic, patient-centered enterprise that fuses biomechanical mastery with real-world adaptability. The integration of foundational methods, rigorous practice, and goal-driven tasks yields improvements not only in walking metrics but in the broader capacity to participate in life. The journey from a clumsy, uncertain gait to a confident, purposeful stride is built on small, deliberate steps—each one chosen to align with a patient’s values, environment, and daily routines. The evidence supports a plan that is as adaptive as the patient’s own recovery curve: assess, target, challenge, and support. When therapists weave together neurodevelopmental principles, strength training, supported treadmill practice, and meaningful, real-life tasks, they give stroke survivors a pathway to walk more freely, to engage more fully with others, and to write new chapters of daily living with renewed dignity.

As gait practice continues to evolve, so does the recognition that walking is inseparable from a sense of autonomy. The field invites clinicians to nurture not just motor recovery but also confidence, adaptability, and resilience. The patient’s story becomes a story of walking forward, one step at a time, with a therapist who helps translate intention into momentum, fear into certainty, and challenge into sustainable independence. In this light, gait training within occupational therapy stands as a central pillar of recovery—a pillar that supports every other aspect of daily life and, ultimately, the patient’s broader life goals.

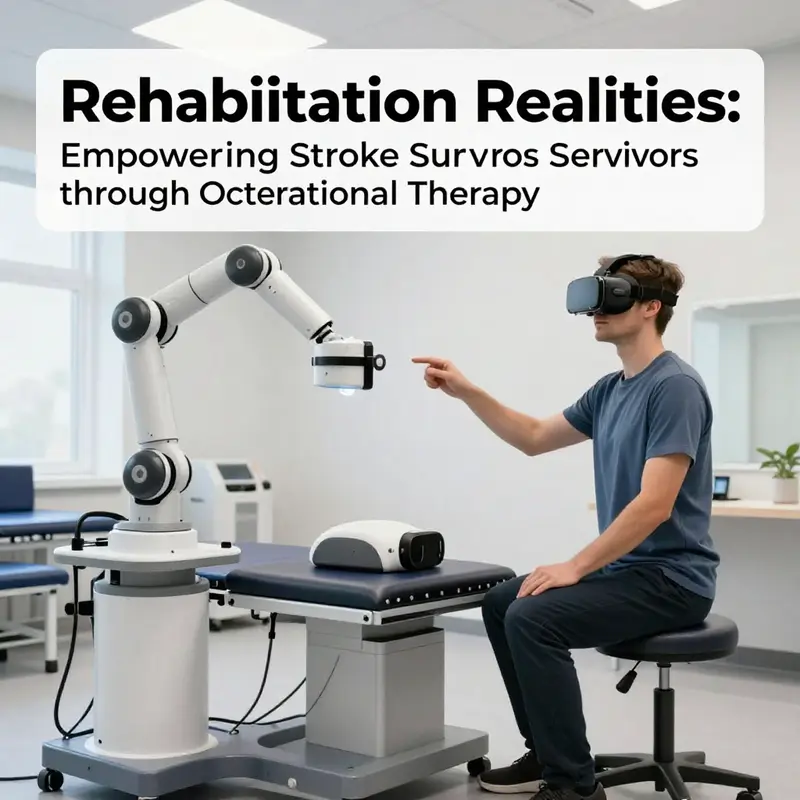

Brain-Driven Recovery: How Robotic, Virtual Reality, and Wearable Technologies Are Redefining Occupational Therapy for Stroke

The recovery landscape after stroke is being reshaped by technologies that translate neurobiology into practical, living progress. Occupational therapy has always centered on enabling meaningful daily life, but the infusion of robotic devices, immersive virtual environments, and precise wearables is turning rehabilitation into a highly personalized, adaptive journey. This convergence rests on a simple truth: the brain relearns through repetition, relevance, and feedback. When therapy aligns with real-life goals and provides reliable insights about movement, patients are not passive recipients of care; they become active agents in shaping their own recovery. The challenge remains how to weave these innovations into everyday practice so that they augment rather than overwhelm, and so that treatment remains accessible, affordable, and congruent with each person’s mental and emotional well-being. In this chapter, we explore how the leading technologies in occupational therapy for stroke are translating science into action, and how therapists, patients, and their families navigate the promise and the practicalities of these advances. The overarching aim is not to replace traditional therapy with gadgets, but to expand the therapist’s toolkit with options that can be tailored to the patient’s unique strengths, weaknesses, and goals, while keeping the human-centered core of OT intact.

Robotic-assisted therapies offer a tangible bridge between intention and action, especially for upper limb recovery. Robotic devices, through precise, repetitive, and task-specific movements, deliver thousands of deliberate practice trials that would be exhausting or impractical by human effort alone. The value of such repetition sits on solid neurophysiological ground: through repeated activation of motor pathways, the brain can reorganize and recruit alternative networks to compensate for damaged areas. For many stroke survivors facing impaired reach, grasp, or arm coordination, robotic systems provide a safe, controlled environment in which therapists can progressively scale task complexity, speed, and range of motion. Importantly, the feedback loop is immediate. A patient can see, hear, and feel cues about movement quality, which helps stabilize learning and reinforce correct patterns before fatigue and frustration set in. In practice, this means therapy sessions that are both efficient and deeply meaningful, as patients repeatedly engage in activities that resemble daily tasks—reaching for a cup, pressing a button on a kitchen appliance, or guiding a utensil to a plate. The resulting data also empower therapists to quantify progress with objective metrics, helping families understand milestones and calibrate expectations.

Yet robotic therapy is more than repetition. It is a platform for progressive challenge that can be calibrated to an individual’s residual function. For some patients with severe impairment, assistive robotics can support movement initiation, gradually shedding assistance as motor control improves. For others, robots can deliver coordinated, bilateral practice that aims to rebalance hemispheric activity after a stroke. The hips and shoulders may demand attention for gait-related training, but the same principles apply: task-specific, high-quality practice in a safe setting translates into real-world capability. The clinical implication is clear—robotic therapy should be integrated with real-life goal setting and ongoing assessment. Therapists must pair robotic sessions with meaningful ADLs, such as dressing or loading a washer, to ensure gains transfer to everyday living. The evidence base, while robust in illustrating improved motor output and movement quality, emphasizes a nuanced view: robotic advantages are clearest when combined with traditional OT strategies and when patient motivation remains high. This is where the therapist’s clinical judgment, empathy, and ability to align therapy with personal goals become indispensable.

Beyond mechanical repetition, virtual reality offers an engineered arc of practice that is both engaging and purposefully designed to mimic everyday tasks. VR transports patients into immersive environments where dressing, cooking, or even managing finances becomes a visually rich, interactive mission. The strength of VR lies in its ecological validity—patients rehearse actions in contexts that resemble their daily lives, which can accelerate the transfer of skills from clinic to home. The environments are adjustable to individual cognitive and perceptual needs, enabling people with diverse impairments to practice safely with feedback that is immediate and forgiving. In practical terms, VR can scaffold complex sequences that would be difficult to replicate with conventional methods alone. A patient who needs to coordinate multiple steps to prepare a simple meal, for example, can practice timing, sequencing, and spatial awareness in a controlled setting where errors become teachable moments rather than discouraging failures.

Evidence from VR-based interventions indicates measurable gains in arm function, balance, and independence in daily activities when compared with conventional therapy alone. The immersive nature of VR can heighten motivation, reduce fear of failure, and sustain engagement across sessions. Importantly, VR systems also provide quantitative data that help therapists monitor progress, adapt difficulty levels, and personalize scenarios to maintain optimal challenge. The patient who starts with limited grasp strength may work on object manipulation within a virtual kitchen, gradually increasing task complexity as dexterity improves. The cognitive and perceptual benefits are worth noting as well: repeated exposure to realistic tasks supports not only motor learning but also executive function, attention, and problem-solving. In practice, the most effective use of VR occurs when it is embedded within a broader OT framework and paired with meaningful home goals, ensuring that what is learned in the virtual world translates to the physical world with fidelity.

Wearable sensors and motion-tracking devices represent a quiet revolution in how progress is perceived and guided. These technologies illuminate the subtleties of movement that are often invisible in routine clinical observations. Real-time monitoring of range of motion, velocity, smoothness, and muscle activation provides objective data that can reveal improvements long before they are visible to the naked eye. This immediate feedback supports dynamic therapeutic adjustments. If a patient shows inconsistent movement quality, a therapist can adjust the regimen on the fly, selecting exercises that target the specific joints or muscle groups under strain and recalibrating resistance or assistance. Wearables also enable remote monitoring, expanding access to care for patients who live far from rehabilitation centers or who face transportation barriers. Daily data streams create a narrative of recovery that families can understand, demystifying the process and reinforcing the patient’s sense of agency. For the therapist, wearables are a compass that points toward the most productive therapeutic path, balancing challenge with manageability and ensuring that every session contributes to a coherent trajectory of improvement.

Alongside these modalities, non-invasive neurostimulation and brain-computer interfaces push the boundaries of how therapy can influence brain activity directly. Techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and allied approaches aim to prime the brain for motor learning, creating a fertile neurophysiological milieu in which practice-driven gains can consolidate more rapidly. In some research contexts, BCIs enable patients to initiate or modulate movements through neural intent, thereby reinforcing motor pathways that are critical for functional recovery. The concept of directly guiding neural activity speaks to a future in which therapy merges with neurotechnology to unlock recovery that once seemed out of reach. It is important, however, to temper enthusiasm with realism. BCIs and neurostimulation require careful patient selection, rigorous safety protocols, and a clear understanding of the limits of current evidence. They are potent tools for certain profiles of stroke survivors and should be integrated thoughtfully into individualized treatment plans rather than adopted as a one-size-fits-all solution.

In the broader clinical picture, innovation does not operate in a vacuum. The adoption of robotic, VR, wearable, and neuromodulatory approaches must be anchored in patient-centered care and supported by robust education and teamwork. Therapists need training that goes beyond device operation to include interpretation of data, integration with cognitive and emotional health, and sensitive communication about progress and setbacks. The data-rich nature of these technologies offers an opportunity to have more meaningful conversations with patients and families about what recovery will look like, which activities are most valuable, and how to structure practice outside the clinic walls. The mental health component, rightly emphasized in the field, gains a new ally in technology when clinicians use it to track mood, frustration, and motivation alongside physical metrics. This alignment is essential for sustainable recovery, because confidence and resilience often determine whether patients continue to engage in meaningful practice after formal therapy ends.

From a practical standpoint, the integration of advanced technologies into OT for stroke requires careful consideration of access, cost, and clinician readiness. Not every setting has budget for a full robotic suite or a high-end VR system, and not every patient desires or tolerates these modalities. The goal is to empower therapists to choose the most appropriate tools for each person and to combine them with traditional OT strategies that have stood the test of time. When therapists connect the patient’s personal goals with the capabilities of these technologies, therapy becomes more than a series of exercises; it becomes a pathway to living more independently and with greater confidence. The literature supports this integrative approach, showing that when technology is used to augment skill acquisition while preserving the therapeutic alliance, outcomes in arm function, balance, and activities of daily living improve meaningfully. Still, progress depends on ongoing research that clarifies which patients benefit most from which interventions, how best to sequence modalities, and how to measure long-term functional independence.

One of the most exciting implications of these innovations is their potential to harmonize physical and cognitive recovery. The tasks that patients learn to perform with robotic devices or in VR environments often require planning, sequencing, and problem solving—skills that are closely tied to cognitive health and mood. Practicing these tasks in meaningful contexts can simultaneously nurture self-efficacy and reduce the psychological barriers to recovery. The connection between mental health and motor recovery is not incidental; it is a fundamental aspect of rehabilitation that OT practitioners have long recognized. When technology enhances engagement, provides clear feedback, and offers a sense of mastery, patients may experience greater motivation, reduce anxiety about daily activities, and sustain participation in therapy. This synergy underscores the need for curricular and supervisory frameworks that educate therapists to address both physical and psychological dimensions of recovery, ensuring that innovative tools enrich rather than fragment the therapeutic process. Within this context, the chapter’s narrative returns to the patient as the central stakeholder—someone navigating a complex, ongoing journey toward independence, with technology acting as a trusted partner rather than a substitute for human care.

The clinical horizon remains dynamic and cautiously optimistic. As new data illuminate how best to harness robotics, VR, wearables, and neuromodulation, therapists will refine decision-making frameworks that balance innovation with safety, feasibility, and patient preference. The practical takeaway is not to chase every new gadget but to cultivate a discerning, patient-centered approach. This involves aligning technology choices with meaningful goals—such as regaining independence in dressing, returning to a preferred hobby, or participating in family routines—and ensuring that every session contributes to a coherent, transferable skill set. It also means acknowledging the realities of stroke heterogeneity: some patients will respond rapidly to certain modalities, while others may require a different mix of strategies or a longer horizon of practice. The therapist’s role remains crucial as guide, coach, data interpreter, and advocate, translating complex technology into approachable, humane care. The clinical journey is thus a collaborative enterprise that weaves science, skill, and empathy into a fabric strong enough to support durable, real-world gains.

Educators and program developers face a parallel imperative: to embed these innovations into training that strengthens clinical reasoning and ethical use. Curricula should emphasize not only how to operate devices but how to integrate technology with patient goals, mental health supports, and environmental adaptations. When clinicians understand the trajectory from evidence to practice, they can select tools that align with each client’s living environment, social supports, and personal values. The result is a more coherent OT experience for stroke survivors—one that respects the rhythm of recovery, honors patient autonomy, and leverages technology as a means to expand possibilities rather than constrain them. In this sense, the innovations described here are less a departure from traditional occupational therapy than a maturation of its core strengths: thoughtful assessment, individualized goals, collaborative problem-solving, and steadfast attention to the person’s quality of life. The technologies become the language through which therapists and clients talk about progress, setbacks, and renewed confidence, a language that can travel from the clinic to the home, from the hospital bed to the kitchen table, and from isolated effort to a shared, hopeful journey.

For readers seeking a bridge between the theory of these technologies and the practice of OT, the literature points to a developing consensus: when implemented with patient-centered goals, robust data feedback, and integrated mental health support, innovations in robotics, VR, wearables, and neuromodulation contribute meaningful gains in independence and life participation after stroke. The field continues to refine best practices, address barriers to access, and expand the range of activities that patients can relearn in ways that feel natural and motivating. As therapists become more fluent in translating digital signals into meaningful, human-centered care, stroke rehabilitation can move toward outcomes that are not only measurable in a clinic but enduring in daily life. This trajectory invites ongoing collaboration among clinicians, researchers, patients, and families—an alliance that ensures technology serves as a bridge to a more active, autonomous, and fulfilling post-stroke life. For clinicians and readers who wish to explore the broader implications of technology in OT as part of ongoing professional growth, the discussion around the role of technology in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy offers a useful gateway to further insight and practical guidance. https://coffee-beans.coffee/blog/what-role-does-technology-play-in-enhancing-patient-care-in-occupational-therapy/

External resource: New Technologies for Stroke Rehabilitation – Frontiers in Neurology (2025) https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1402729

Reclaiming Daily Life: The Mental Health Core of Occupational Therapy Exercises After Stroke

Recovering from a stroke is not only about regaining motor skills; it is about restoring daily life, mood, and meaningful participation. In occupational therapy (OT), the goal is agency and engagement, not just repetition. Evidence shows mood, resilience, and well-being influence how fully someone can relearn tasks and rejoin routines. Therefore OT should integrate mental health into every practice, from ADLs to gait training. When therapy feels purposeful and person-centered, motivation sustains and gains transfer to real life.

A pivotal framework is OPC-Stroke, a strengths-based, client-centered approach that couples practical skills with emotional support. The therapeutic relationship becomes a mechanism for reducing anxiety and boosting confidence. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness guide task selection and feedback.

Integrating mental health requires strategies woven into daily tasks. Brief mindfulness, breathing checks, and real-life goal setting that adapts over time can support emotional regulation and engagement. Positive reinforcement for small wins helps rebuild self-efficacy and sustain motivation during the slower pace of recovery.

Practically, handwriting, buttoning, and card sequencing become opportunities to practice motor control while cultivating patience, attention, and meaning. Group activities and social engagement strengthen mood and participation, and screening for mood with tools like PHQ-9 can flag issues needing broader support through collaboration with mental health professionals.

Emerging therapies remind clinicians to consider the mind-body connection, but the core remains: a motor task is also an avenue for autonomy and purpose. The therapy environment should feel safe and hopeful, with space to fail and try again. Clinician education should embed mental health content in OT training so future therapists address both domains cohesively.

Ultimately, OT exercises after stroke should be envisioned as integrated experiences where movement and mental health reinforce each other, helping survivors reclaim daily life with confidence and resilience. This chapter outlines how to blend physical practice with psychological well-being to support durable recovery.

Final thoughts

Incorporating targeted occupational therapy exercises for stroke recovery can significantly enhance the quality of life for survivors. Addressing both physical and mental health needs through an integrative approach improves rehabilitation outcomes and helps build resilience in patients. As business owners, investing in these therapeutic methods not only aligns with best practices but also underscores your commitment to holistic patient care.