In the dynamic landscape of healthcare, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) are two crucial forms of rehabilitation that cater to patients’ diverse needs. While both aim to improve patients’ quality of life, their approaches, goals, and techniques vary significantly. For business owners in the healthcare sector, understanding these differences is essential for providing holistic patient care. The following chapters will explore the distinct goals and methods of PT and OT, delve into specific techniques and interventions used by each discipline, identify the patient populations they serve, examine the role of technology in their practices, and highlight the synergies that arise from collaboration. This deeper insight will enable business owners to streamline operations and enhance service offerings in their healthcare environments.

Moving Toward Independence: How Physical and Occupational Therapy Align Yet Distinctly Serve the Body and Daily Life

When people think about rehabilitation after an injury or illness, they often encounter two names that sound similar but point to different missions within the same journey: physical therapy and occupational therapy. Together, these disciplines aim to restore quality of life and independence, yet their routes diverge in what they prioritize and how they go about it. This chapter unpacks that distinction not as a rigid separation but as a complementary map for navigating recovery. The broader article topic—physical therapy versus occupational therapy—asks not which one is better but how each discipline uniquely targets the facets of function that matter most to a person’s daily life. The distinction begins with focus and goal. Physical therapy centers on movement itself. It seeks to restore or improve the body’s capacity to move—strength, balance, flexibility, endurance, and coordinated control. The overarching aim is to address impairments that limit mobility, whether the limitations arise from a musculoskeletal injury, a neurological event, or a condition that undermines cardiovascular endurance. In practice, that means a PT program leans heavily on therapeutic exercises designed to retrain muscles, joints, and the nervous system to work together again. Manual therapy may accompany exercise to improve joint mobility, and clinicians often guide patients through gait training to re-establish a safe and efficient walking pattern. Modality-based interventions—such as heat, cold, electrical stimulation, or ultrasound—are used to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and facilitate tissue healing. The clinician’s toolkit is thus oriented toward restoring the body’s physical capacity, with measurable outcomes like range of motion, strength, balance, and functional endurance. The language of PT reflects this emphasis: every movement system, from a stiff knee to a weak core or a deconditioned heart, becomes a target for intervention.

Occupational therapy, by contrast, orbits around the activities that give life its meaning. OT’s primary objective is not movement for movement’s sake but the restoration or enabling of everyday functioning. It asks: What tasks matter most to the person at this stage of life? Can they dress themselves, cook a meal, manage personal care, or return to work? The answers drive a different kind of therapeutic equation. Rather than focusing solely on the mechanics of a body part, OT centers on the person’s ability to perform “occupations”—the purposeful and meaningful activities that constitute daily living. When a stroke or a cognitive change disrupts these activities, the OT conversation shifts toward practical solutions that support independence and safety in real-world contexts. The interventions reflect this orientation. Task-specific training helps people relearn how to complete daily activities in situ, often using adaptive equipment and environmental modifications. An OT might introduce adapted utensils to compensate for limited hand function, rearrange a kitchen to accommodate a wheelchair, or train someone to manage personal care routines with strategies that reduce fatigue and promote confidence. Cognitive-behavioral approaches may address the emotional and motivational barriers that accompany functional limitation. The work is not merely about completing tasks but about making daily life feel purposeful and controllable again. These two tracks—movement restoration and daily-life adaptation—are not mutually exclusive. In a rehabilitation setting, PT and OT frequently collaborate to create a coherent, person-centered plan. After an event such as a stroke, a patient may begin with PT to re-establish basic mobility, walking ability, and postural control. Once there is a foundation of mobility, OT can step in to re-teach or reconfigure how the patient approaches dressing, bathing, meal preparation, and community participation. The sequence is not universal, but the logic is clear: without sufficient movement, daily tasks can remain out of reach; without strategies to perform those tasks, mobility gains may struggle to translate into real-life independence. The synergy between PT and OT is most evident in the shared goal of reducing disability and enhancing quality of life, yet their methods and milestones illuminate two different facets of recovery. The body’s ability to move, as emphasized by PT, creates the raw potential for independence. It builds strength and endurance so that tasks do not exceed the person’s physical limits. The OT emphasis on meaningful activity translates that potential into practical, daily power. It teaches the person to select, adapt, and negotiate tasks in ways that align with personal values, living environment, and social roles. Taken together, they form a holistic approach to rehabilitation—one that respects the integrity of the body while honoring the idiosyncrasies of the person who inhabits that body. The outcomes reflect this dual focus. Physical therapy often aims to reduce pain, increase range of motion, and restore functional performance through improved movement mechanics. When successful, a patient can walk farther with less fatigue, rise from a chair more steadily, or perform daily tasks with greater efficiency. Occupational therapy, meanwhile, measures success through functional independence and participation. A patient who can dress independently, prepare meals safely, manage medications, or re-enter the workplace speaks to OT’s core achievement: the person’s ability to live autonomously and engage in life’s roles with confidence. The two tracks also share a practical emphasis on safety and prevention. PT benefits include not only restoring function but also addressing risk factors that could lead to reinjury, such as poor balance or deconditioning. OT carries forward the risk-management perspective by focusing on the environment in which a person operates. A simple kitchen reconfiguration can prevent falls; a timer or adaptive tools can prevent fatigue-related errors in self-care. These considerations reflect a broader principle of rehabilitation: care is patient-centered not only when it targets the body but also when it adapts the world around the patient to accommodate limitations without diminishing dignity or autonomy. The collaboration between PT and OT is most effective when goals are explicit and aligned with the person’s life context. The care plan benefits from a shared assessment language that translates a patient’s aspirations into concrete tasks and measurable outcomes. This approach ensures that improvements in the clinic translate to meaningful gains at home, at work, or in social settings. It also encourages continuity of care, as a patient moves from mobility-focused rehabilitation to routines that support ongoing independence. The distinction between PT and OT, then, is not a hierarchy but a spectrum of expertise that addresses different dimensions of function. PT strengthens the “body in motion”; OT shapes the “life in motion.” For someone recovering from a neurological event, for instance, PT might restore walking and balance, while OT helps relearn how to prepare a meal or manage personal care with adapted equipment. For a working adult coping with a chronic condition, PT may improve stamina for job tasks, and OT can optimize the workplace and daily routines to maintain productivity and safety. This integrated perspective emphasizes that rehabilitation is most effective when it honors both the physiology of movement and the psychology of living with impairment or disability. It also highlights why many rehabilitation teams organize care around the patient’s priorities, not the professions’ boundaries. When patients understand that PT is about how well they can move and OT is about how well they can live with those movements, the care plan becomes a bridge rather than a barrier. For readers seeking a concise comparison, a practical resource frames the discussion around a direct question: occupational therapy versus physical therapy. The paired emphasis on daily life versus movement offers a useful heuristic for patients and families evaluating referrals or choosing therapies that align with personal goals. For a quick reference, you can explore this overview: occupational therapy vs physical therapy. While this chapter has focused on the core distinctions, it is essential to remember that each chapter in this article builds toward a nuanced appreciation of how PT and OT together support independence, safety, and well-being. The narrative is not about choosing one path over the other but about recognizing how their complementary skill sets can be woven into a single, patient-centered rehabilitation plan. In practice, clinicians often measure progress with parallel milestones: improvements in strength, range of motion, and endurance on one hand; and increases in independence, confidence in performing everyday tasks, and the ability to participate in meaningful activities on the other. This dual lens reflects the holistic aim of rehabilitation: to restore not only what the body can do but also what a person can do with their life. For further reading that broadens the lens to the cognitive and emotional dimensions that OT sometimes addresses, external resources such as overview articles on occupational therapy can provide additional context about how mental health and environmental factors intersect with daily function. External resource: https://www.informedhealth.org/what-is-occupational-therapy/.

Synchronizing Steps and Skills: Techniques and Interventions in Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy

In rehabilitation, clinicians map two complementary journeys toward independence. Physical therapy and occupational therapy start from shared goals—reducing pain, restoring function, and helping people reclaim meaningful lives. Yet they chart different routes. Physical therapy, at its core, pursues movement more than any other outcome. It is the discipline that helps a person bend, lift, walk, and breathe with less effort and less discomfort. Occupational therapy, by contrast, focuses on the tasks that give life its texture: getting dressed, cooking a meal, managing finances, returning to a job, and participating in the rhythms of home and community. Together, they form a seamless continuum of care, where movement and meaning reinforce one another, and where the best outcomes arise from deliberate collaboration rather than isolated efforts. The most powerful chapters in a patient’s recovery are often written when PT and OT work in concert, aligning movement capacity with daily capability and personal purpose.

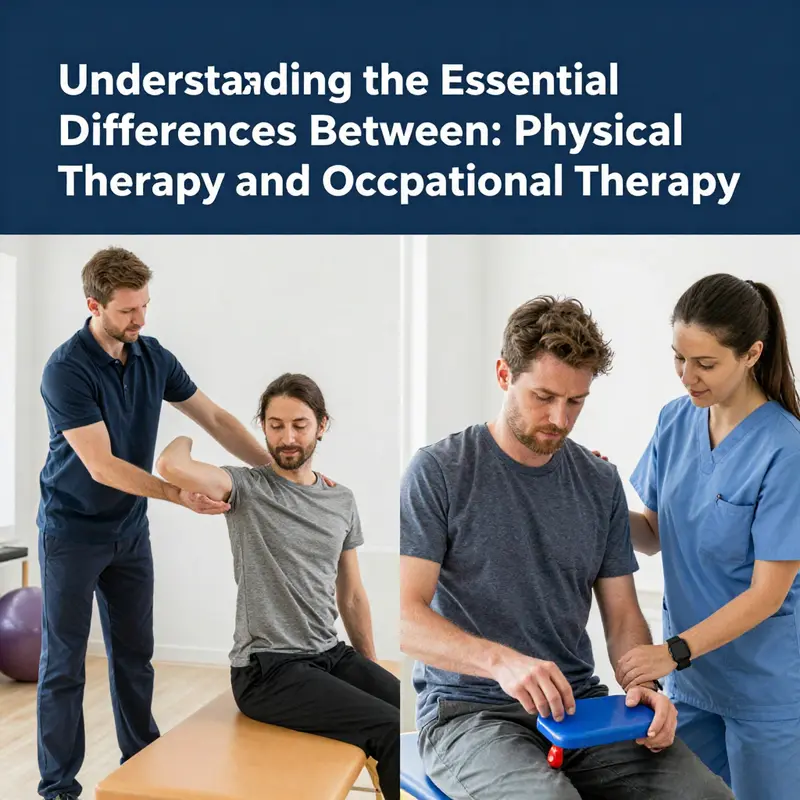

Physical therapy is built on restoring or enhancing the body’s leverages for function. Therapists begin with careful assessment of movement, strength, balance, and endurance. They look at how joints move, how muscles fire, and how the nervous system coordinates signals to the limbs. Hands-on techniques are a familiar staple: manual therapy that mobilizes restricted joints, soft tissue work that eases stiffness, and targeted stretching to unlock range of motion. But practice extends beyond the table. A broad portfolio of exercise prescriptions forms the backbone of PT: graded strengthening programs that rebuild power in key muscle groups, flexibility routines to release tightness, and aerobic conditioning to improve stamina and cardiovascular health. The goal is not just to restore motion but to reestablish reliable, efficient patterns of movement that can be sustained in daily life.

Gait training is a particularly vivid example of PT’s movement-first orientation. For individuals recovering from stroke or other neurological events, regaining a stable, purposeful stride may require both traditional therapy and advanced modalities. Therapists may guide a patient through repetitive stepping patterns, gradually increasing speed, symmetry, and control. When appropriate, they introduce assistive devices or robotic-assisted technologies that adapt to the patient’s progression. End-effector devices and other adaptive systems, though technically sophisticated, serve a simple purpose: to provide precise, measurable practice that translates into steadier walking. Even in the absence of high-tech devices, PT relies on practical, real-world tasks—standing from a chair, stepping over thresholds, navigating uneven surfaces—to restore confidence in movement. Pain management is woven through these interventions, with modalities such as heat, cold, or electrical stimulation used selectively to reduce flare-ups so that exercise can proceed with less resistance.

Balance and proprioception receive careful attention because fall risk remains a central concern across ages and conditions. PT approaches balance not as an abstract concept but as a set of retrievable skills. Therapists challenge a patient with varied surfaces, multi-sensory cues, and progressive perturbations to rebuild the brain’s maps for movement. The aim is to minimize fear of movement, which often accompanies deficits after injury or illness. In neurological rehabilitation, PT may also incorporate neuromuscular retraining strategies designed to rewire motor patterns, a process that can be aided by feedback from real-time measurements and objective progress markers. Across settings, PT emphasizes repeated, purposeful practice—feedback-rich, goal-oriented sessions that translate into tangible gains in mobility, endurance, and functional capacity.

Occupational therapy, while overlapping with PT in several domains, centers on the tasks that define everyday life. The OT practitioner performs a patient-centered analysis of activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. They ask not only whether a person can reach or grip, but whether they can accomplish a morning routine without frustration, whether they can prepare a meal safely, or whether they can manage work tasks with reasonable autonomy. The assessment extends beyond the body to the environment itself. A kitchen layout, a bathroom, a workplace, and even community spaces are scrutinized for safety, efficiency, and accessibility. When limitations are identified, OTs design adaptive strategies that preserve agency. They introduce adaptive equipment—grab bars, adapted utensils, dressing aids—and they suggest environmental modifications that can dramatically reduce barriers to independence. The emphasis is not simply on doing a task but on doing it in a way that preserves dignity, fosters self-efficacy, and sustains participation in meaningful roles.

Cognitive and psychological dimensions also surface within OT. A stroke survivor, for example, might face attention lapses, memory challenges, or impaired problem-solving. OT’s repertoire can include cognitive rehabilitation to help reframe these barriers so the person can plan, sequence, and monitor activities despite cognitive changes. Behavioral strategies and stress management techniques may be woven into therapy to address anxiety that can accompany disability. In this sense, OT often extends beyond pure task execution to encompass the person’s emotional state and sense of control. The environment remains a central partner; OT practitioners routinely tailor living and workspaces to reduce cognitive load, improve safety, and promote independence. This might mean simplifying a daily routine, organizing a workspace to minimize distractions, or training a client in the use of a calendar and reminder system that aligns with their cognitive strengths.

Despite their distinct emphases, PT and OT share a philosophy grounded in patient-centered care. The aim is not merely to repair a body part or complete a task but to restore the person’s ability to engage with life as they define it. Both disciplines regularly incorporate mind–body approaches that speak to the whole self. Mindfulness, breathing techniques, and gentle movement forms like yoga or tai chi can be valuable adjuncts for pain management, anxiety reduction, and improved body awareness. In practice, therapists may blend such strategies with physical or functional tasks to support a holistic recovery. The result is a pathway that treats pain and impairment while also nurturing confidence, resilience, and purpose.

Interprofessional collaboration emerges as a guiding principle in high-quality rehabilitation. The patient’s goals often require a blend of movement re-education, task-specific training, and environmental adaptation. When PT and OT collaborate, they align their assessments, set shared goals, and pace interventions to ensure that progress in mobility translates into practical gains at home, work, or school. A cohesive plan might begin with PT-driven restoration of leg strength and gait stability, followed by OT-driven strategies that integrate those gains into dressing, cooking, and independent community access. Moreover, both professions recognize that progress is not always linear. Flare-ups, fatigue, or cognitive fluctuations can shift priorities. In these moments, therapists communicate openly, reassess feasibility, and adjust tasks to maintain momentum without compromising safety or well-being.

This integrated approach also respects the patient’s context and preferences. Some individuals will prioritize return to a specific activity—playing with grandchildren, returning to a preferred job, or managing self-care without assistance. Others may place emphasis on safety and autonomy at home, particularly if environmental barriers are substantial. Therapists honor these priorities by calibrating the intensity and focus of interventions. They may negotiate a phased plan, where movement improvements are paired with practical adaptations that enable the person to participate in valued roles immediately, even as longer-term functional capacities continue to be developed. In every case, the patient’s voice remains central: goals are co-created, progress is co-evaluated, and success is defined in terms that matter to the individual, not solely by clinical metrics.

The techniques and interventions of PT and OT, while distinct, map onto a shared trajectory of rehabilitation. Physical therapy often lays the groundwork by restoring the physical capacity needed for daily life. It rebuilds strength, endurance, and motor control with precise, repeatable practice. Occupational therapy builds on that foundation by translating capacity into purposeful action within real-world contexts. It filters the gains through the lens of daily function, ensuring that improvements translate into safer, more autonomous living. In practice, a patient may experience this continuum as a single, coherent process rather than two separate tracks. The therapist’s role becomes that of a conductor who harmonizes multiple instruments—movement, cognition, environment, and emotion—so that each element supports the others.

As the chapter on techniques and interventions suggests, the most compelling rehabilitation stories arise where PT and OT communicate early and often. Assessments conducted at the outset inform a joint strategy that respects both the body and the life that the person longs to live. The patient’s home, work, and social networks become part of the therapeutic map, with interventions designed to bridge the gap between clinical improvement and everyday mastery. A well-tuned rehabilitation plan positions the patient to experience progress in tangible ways: the ability to tie shoelaces after a difficult morning, the steadiness of a step taken with confidence, or the sense of competence that comes from preparing a simple meal without assistance. These are the moments that reveal the true value of integrating physical therapy and occupational therapy.

For those seeking more on how these disciplines intersect, consider one exploration of the comparison between the two fields. The article on occupational therapy versus physical therapy offers a concise, grounded overview that can help patients and families understand expectations, pathways, and roles in care. occupational therapy vs physical therapy provides a accessible entry point to the broader discussion of how each discipline contributes to recovery.

In sum, physical therapy and occupational therapy are distinct in emphasis yet united in outcome. PT paves the road by rebuilding movement, strength, and mobility. OT clarifies the route by enabling tasks that matter, shaping environments, and supporting independence. Together, they form a comprehensive approach that respects the body’s biology and the person’s lived experience. The most effective rehabilitation honors both paths, weaving them into a single, patient-centered journey toward restored function, meaningful participation, and a life that feels controllable and purposeful again. As research advances and clinical techniques evolve, the alliance of movement and daily living remains a constant, guiding practitioners toward care that is not only effective but deeply human.

External resource for further reading on professional standards and practice in physical therapy is available at https://www.apta.org.

Serving a Spectrum of Needs: How Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy Reach Diverse Patient Populations

Rehabilitation is not a single path but a braided one, where movement and daily life intertwine to shape a person’s independence. Physical therapy and occupational therapy are two threads of that braid, each with a distinct focus yet a shared aim: to restore function, reduce barriers, and help people re-engage with the activities that give life meaning. When we look at the populations these disciplines serve, the landscape appears broad and interconnected. PT tends to be the workhorse for restoring movement, strength, balance, and physical capacity after injury, surgery, or illness. OT tends to be the daily-life partner, guiding people back into dressing, cooking, managing finances, or navigating work tasks. But in real-world care, the distinction is not a hard line. Many patients require both therapies in a coordinated plan, as the body’s capacities and the person’s goals overlap across physical and functional domains. A large-scale snapshot of practice illuminates this integration. In a study that followed 104,295 patients, a striking 85.2 percent received some form of rehabilitation, underscoring how essential therapy services are in modern care. Within that cohort, a majority—61.5 percent—received both physical and occupational therapy, signaling a common pathway where movement and daily function are treated together. An additional 22.0 percent received physical therapy only, while 1.7 percent received occupational therapy only. Those numbers reflect the reality that many rehabilitation needs travel with complex totals of muscle strength, motor control, cognitive function, and environmental demands. They also hint at how care plans are tailored to patient goals and settings, from acute hospitals to community programs and home environments. The implication is clear: successful rehabilitation often depends on a bridge between improving how the body moves and enabling how the body lives within the world it encounters every day.

In appreciating the populations served, it is helpful to ground the discussion in the typical kinds of conditions PT and OT are called to address. Physical therapy is frequently deployed for musculoskeletal injuries—sprains, strains, fractures, and arthritis—where restoring movement and load-bearing capacity is essential. Postoperative recovery after joint or soft-tissue surgeries is another major arena, where PT helps patients regain strength, correct movement patterns, and reestablish functional gait. PT also plays a crucial role for individuals with neurological conditions, such as stroke or spinal cord injury, where re-learning movement and balance can be life-changing. Chronic pain management is another pillar, with therapeutic exercises and modalities designed to reduce pain, improve endurance, and enhance overall physical performance. On the other side of the coin, occupational therapy concentrates on enabling people to perform activities of daily living and meaningful tasks—dressing, bathing, cooking, caregiving, and returning to work or school. OT emphasizes the person in their environment, not just the movement. It involves environmental assessment and modification, provision of assistive devices, and coaching to adapt tasks so they can be completed safely and with greater independence. OT serves a wide spectrum—from children with developmental disabilities who need foundational skills for independence to adults navigating cognitive or mental health challenges that affect daily routines. In clinical and community settings alike, OT clinicians assess the person’s home, school, or workplace and design supports that remove barriers to participation. This might include adaptive utensils for dining, compensatory strategies for memory challenges, or gradual job- or school-related task modification to accommodate energy limits or cognitive load.

The patient journeys that emerge from these two paths are often collaborative and iterative. Consider a person recovering from a stroke who initially needs PT to regain motor control and balance, followed by OT to relearn self-care and community participation. Or a patient with a knee replacement who benefits from PT to restore strength, endurance, and gait, complemented by OT to adapt the home environment and teach safe methods for daily tasks. In younger populations, OT frequently focuses on habilitation or rehabilitation for developmental disorders, ensuring foundational skills translate into school functioning and social participation. In older populations, OT’s emphasis on home safety, adaptive devices, and cognitive support helps prevent falls and supports aging in place. Across these scenarios, both therapies rely on education, coaching, and collaboration with caregivers and other professionals. The same patient may present with physical limitations that influence cognitive performance, or cognitive fatigue that affects engagement in movement-based exercises. This complexity is why integrated care models, where PT and OT operate as a coordinated team, often yield better functional outcomes than when each discipline works in isolation.

Within physical therapy, the typical course of care highlights a practical rhythm of repeated visits aimed at building and reinforcing gains. The data indicate patients who attend PT sessions accumulate a meaningful number of encounters—on average, about 11.75 visits across the course of rehabilitation, with primary treatment patients averaging roughly 10.4 visits. These figures are not mere counts; they reflect how progress unfolds over time and how therapy plans are adjusted in response to improvements, plateaus, or new goals. The repeated contact also signals the potential for cumulative benefits—strength gains, motor learning, and improved confidence in movement. For many patients, this ongoing engagement is the bridge between a clinical improvement and a real-world return to movement in daily life. It also speaks to the importance of access, continuity of care, and the ability of therapists to tailor progression in a way that respects a patient’s schedule, motivation, and pain levels.

Occupational therapy, while sometimes perceived as less centralized around movement, addresses a different but equally essential set of outcomes. OT’s community focus and home-centered approach help patients translate physical gains into practical independence. They teach health literacy and self-management strategies, coach patients in task-specific techniques, and collaborate with families to support carryover beyond the therapy session. The emphasis on collaboration and coaching is not a soft add-on; it is central to how OT enables people to re-engage with occupations that give life meaning—whether that is managing a household, returning to work, or participating in leisure activities. In cases of developmental disorders, OT may help children acquire skills for school participation, refine fine motor control, and develop adaptive strategies that support learning. For cognitive impairments or mental health challenges, OT integrates cognitive supports and environmental modifications to reduce symptoms and facilitate participation in daily routines. The setting matters, too. OT’s strength lies in community-based work, home assessments, and practical coaching that helps people navigate the realities of daily life in the environments where they live, learn, work, and play.

The numbers from the large-scale study reinforce the practical importance of these roles and their intersection. They illustrate that rehabilitation in modern care is less about choosing one path and more about crafting a composite plan that respects movement and function as inseparable elements of independent living. The high proportion of patients receiving both PT and OT—more than half of the studied population—speaks to the reality that real-world recovery often requires a dual focus. When both therapies are involved, clinicians can synchronize goals so that improving muscle strength and mobility dovetails with teaching adaptive techniques, environmental modifications, and strategies for balancing daily demands. This synchronization is particularly valuable in complex cases, such as long-term neurological conditions or post-surgical rehabilitation, where movement and daily function are tightly linked. The research also suggests the importance of considering patient characteristics and diagnostic factors when planning therapy. Demographics, comorbidities, and specific diagnoses influence which therapies are emphasized, how often patients attend sessions, and what outcomes are prioritized. For clinicians and policymakers, these insights underscore the need for flexible care pathways that can adapt to diverse needs and contexts, ensuring that both PT and OT are accessible and appropriately matched to patients’ goals.

To readers seeking a concise comparison as they navigate care options, a helpful overview is available here: What is the difference between physical therapy and occupational therapy?. This resource can ground decisions about referrals, especially when patients and families are weighing how to allocate time, energy, and resources across services. Beyond this, the broader implication of the data is clear: when PT and OT work in concert, patients experience a more comprehensive restoration of function and independence, which can translate into improved participation in work, school, and home life. The combined approach also reflects an essential ethical dimension—recognizing that recovery is not just about restoring the body’s mechanical abilities but about supporting the person as a whole, including their environment, routines, and social supports. In this sense, PT and OT are not competing modalities but complementary lenses through which rehabilitation can be tailored to the person’s unique life context. As care continues to evolve, the wheel of rehabilitation turns more smoothly when practitioners collaborate, when patients are empowered with knowledge about their options, and when health systems cultivate pathways that value integrated therapy as a standard of care rather than a special arrangement.

For those who want to explore the empirical underpinnings of these patterns and to understand how patient characteristics shape therapy utilization, the original research offers a detailed map of demographics, diagnostic factors, and session frequencies—an essential reference for clinicians, administrators, and researchers aiming to optimize rehabilitation pathways for diverse populations. This body of work underlines the shared mission of PT and OT: to transform limited movement and challenged independence into regained capability and meaningful participation in daily life. It also points toward a future in which multidisciplinary teams coordinate seamlessly, guided by patient goals and real-world outcomes, ensuring that every individual has access to the supports needed to live as independently as possible. For those who wish to delve deeper into the data, see the external resource below for more comprehensive findings.

External resource: Leatherwood, W., et al. 2024. Demographic and Diagnostic Factors in Physical Therapy. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10923258/

Technology as the Bridge Between Movement and Daily Life: Integrating Digital Tools in PT and OT

Technology has quietly become the scaffolding of modern rehabilitation, threading physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) into a shared, increasingly digital practice. The result is a culture where clinicians can measure movement with greater precision, tailor exercises to individual needs, and extend care beyond the clinic walls. This shift is not a simple upgrade of equipment; it is a reconceptualization of how movement, function, and daily life are understood, assessed, and supported. In PT, technology steadyizes and expands the domain of physical restoration. Therapeutic exercises, manual techniques, gait training, and modalities such as heat, cold, and electrical stimulation remain core tools, but their application is now guided by data streams and remote observation that help clinicians track progress with nuance. Devices that manage temperature, deliver ultrasound, or provide electrical stimulation are not merely assistive; they become feedback loops. When a patient performs a set of leg presses or ankle pumps, sensors can quantify range of motion, speed, and symmetry, turning what used to be a qualitative impression into an objective trajectory of recovery. This data-driven layer supports decisions about progression, modification, or cessation of treatment and helps ensure that interventions remain aligned with functional goals rather than just isolated measures of strength or ROM. The lived experience of movement also informs the design and acceptance of these tools. Therapists learn, often in collaboration with people living with disability, how to adapt devices for real-world use. A custom orthotic or a mobility aid can be refined through patient feedback, ensuring that the device not only reduces pain or improves biomechanics but also fits into daily routines in a way that motivates consistent practice. In this sense, technology in PT is both a therapeutic instrument and a partner in goal setting, a facilitator of movement that respects the body’s limits while inviting its potential for change. While PT remains steadfast in promoting physical function, it is increasingly attentive to the ways movement enables meaningful life activities. This broader view aligns with the OT perspective that rehabilitation is not only about restoring joint range or strength but about reclaiming the capacity to perform daily tasks with confidence and safety. The integration of digital tools in PT thus serves as a bridge between motor recovery and the practical realities of living—caring for a home, returning to work, or managing community participation. The same bridge concept extends into OT, where technology is both an enabler of daily independence and a lens for understanding a person’s environmental fit. OT has always focused on activities of daily living (ADLs) and the meaningful tasks that give structure and purpose to life. Today’s OT practice increasingly relies on telehealth platforms to connect with clients who face geographic or mobility barriers. Virtual sessions can guide caregivers in how to set up a home environment that supports safe performance of tasks like dressing, cooking, or laundry, while remote assessments can capture how a client interacts with household spaces over time. The accessibility improvements are not incidental; they reflect a deliberate reimagining of service delivery so that therapy travels with the patient, not merely to the patient. Telehealth, in particular, has become a conduit through which OT can extend expertise to underserved communities, monitor progress, and intervene promptly when challenges arise. In addition to remote care, wearable sensors and virtual reality (VR) environments have opened new windows into fine motor control, executive function, and cognitive processing. Wearable biosensors provide real-time data on movement patterns, posture, heart rate, and fatigue. When a client practices buttoning a shirt or tying a shoelace in a VR simulation, therapists can observe precision, timing, and sequencing in a controlled, repeatable context. VR also offers a safe space to rehearse complex activities—like grocery shopping or managing finances—before attempting them in the real world. These digital simulations give OT clients opportunities to rehearse steps of independence without fear of failure, building confidence and improving the transfer of skills to home and work environments. While PT and OT each leverage such technologies, the collaboration between the two disciplines becomes more seamless as data travels between systems. Electronic health records (EHRs) and interoperable data platforms allow therapists to share progress notes, reassess goals, and align treatment plans across disciplines. For instance, a PT team member may document improvements in postural control and gait stability, while an OT colleague notes enhanced performance in self-care tasks. This shared data pool supports a holistic understanding of a person’s functioning and helps prevent fragmentation of care. Yet, the embrace of technology is not without caveats. The research landscape emphasizes the need for clinical judgment to anchor devices in patient-specific contexts. The same modalities that can alleviate pain and stiffness—such as heat, cold, and electrical stimulation—require careful application. Contraindications must be respected, including risk factors for pacemaker patients or skin sensitivity at electrode sites. Clinicians must balance the benefits of a modality with its potential risks, ensuring that user safety remains paramount. Moreover, as devices proliferate, clinicians face questions about accessibility, training, and cost. Technology should reduce barriers, not introduce new ones. This is where the human-centered design of tools becomes critical. When therapists collaborate with patients to co-create solutions—selecting modalities, calibrating sensor thresholds, or choosing home equipment that fits living spaces—the result is greater adherence and better outcomes. The social and cultural dimensions of technology also shape its adoption. Attitudes toward the body, the acceptability of monitoring, and preferences for autonomy all influence how patients engage with digital rehabilitation. In many communities, digital literacy and access to reliable connectivity determine who benefits from telehealth, VR, or wearable monitoring. Therapists must be prepared to address these disparities, offering alternative pathways when needed and advocating for broader access to digital resources. This broader view of technology’s role is echoed in the professional literature, which calls for evidence-informed practice, ongoing education, and thoughtful integration of digital tools into standard care. The promise of data-driven personalization is not a guarantee of better outcomes by itself; it requires clinicians who can translate numbers into meaningful goals, adjust plans as new information emerges, and maintain patient-centered communication throughout the process. The synergy of PT and OT in this technologically enriched era is most powerful when the patient remains at the center. Technology does not replace the therapeutic relationship; it amplifies it. The clinician’s expertise—spanning anatomy, biomechanics, cognitive function, psychology, and sociology—remains the compass guiding how tools are applied. Through careful assessment and collaborative goal setting, PT focuses on restoring movement and physical function while OT emphasizes the ability to perform daily tasks with independence and safety. Together, they create a continuum of care where movement and daily living are not treated as isolated domains but as interconnected facets of a person’s life. The patient’s home, workplace, and community become living laboratories where digital tools capture authentic activity, track progress, and tailor interventions to evolving needs. In this sense, technology is less about gadgets and more about a shared language that translates clinical insight into practical, sustainable change. The external world of research, policy, and practice guidelines further shapes the trajectory of this evolution. Evidence-based adoption of telehealth, VR, and wearables requires rigorous study and clear criteria for when and how these tools should be used. For OT, the push toward remote assessment and home-based intervention aligns with broader goals of expanding access and supporting community-based rehabilitation. The technology trends highlighted in practice surveys reinforce a move toward integration, interoperability, and patient-centered data use. As these developments unfold, clinicians must remain vigilant about privacy, consent, and data security. The integrity of patient information, the ethical use of monitoring, and transparent communication about what data are collected and how they inform care are essential to maintaining trust. The grand arc of technology in PT and OT, then, is not simply a catalog of devices but a narrative about enabling human potential. It is a narrative that acknowledges the value of hands-on manual skills and the dignity of becoming more self-sufficient in daily life. It is about designing home environments that accommodate aging bodies and evolving cognitive needs, about remote check-ins that prevent setbacks, and about learning from patients as co-designers of their own rehabilitation journey. For readers seeking a deeper lens into how technology shapes OT, a recent synthesis of practice trends provides a comprehensive map of telehealth, wearables, VR, and EHR adoption across the field. See the resource for a broad view of how digital tools are reshaping occupational therapy practice, and how therapists balance innovation with the ethical obligations of care. The same current also informs PT, where sensors and analytics enhance the art and science of movement restoration. The integration of these technologies is not a destination but a continuous process of refinement—of better measurement, clearer communication, and more responsive care. It invites practitioners to be curious, adaptable, and collaborative with patients, families, and communities. In practice, this means clinicians continuously translate data into action: calibrating exercise intensity, adjusting home-modification recommendations, guiding patients through remote check-ins, and using VR scenarios to rehearse real-life tasks with confidence. It means fostering partnerships with patients that honor their lived experience, their cultural contexts, and their personal goals. The end result is rehabilitation that feels personal, practical, and purposeful—an approach in which technology supports the human work of restoring movement and reclaiming daily life, side by side. For additional reading on how technology trends are shaping OT practice, consider exploring a recent survey of occupational therapists and their digital practices. Additionally, the chapter draws on a broader synthesis of technology’s impact across PT and OT, emphasizing a future in which data-informed decisions empower more precise, equitable, and accessible care. See the external resource for a comprehensive view of technology trends in occupational therapy practice. Technology Trends in Practice: A Survey of Occupational Therapists. Within OT-specific contexts, consider related discussions on how technology aids in adapting environments and improving adherence, such as the article on the role of technology in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy. To readers seeking practical examples closely tied to daily life, the following internal link offers insights into how technology supports OT in real-world settings: What role does technology play in enhancing patient care in occupational therapy?.

Moving Together, Living Better: Integrated Physical and Occupational Therapy in Rehabilitation

Collaborative rehabilitation rests on a simple premise: movement and daily living are intertwined, and healing happens most fully when therapists speak the same language about both. Physical therapy and occupational therapy arrive at the patient from different doors, yet their work overlaps in the corridor, at the bedside, and in the home. PT is often the technician of movement intent, training strength, balance, and endurance; OT is the architect of daily function, shaping tasks that restore independence. In rehabilitation, the goal is not merely to restore a leg or a hand, but to reconstruct a life, with routines that feel doable and meaningful.

Patients who have suffered trauma or surgery benefit when PT and OT plan together from day one. A joint assessment can reveal how a single movement deficit translates into a missed activity of daily living, and conversely, how difficulty with dressing might alter walking patterns due to fatigue or fear of falling. This interplay is not a luxury; it is a practical approach that accelerates progress and reduces the risk of setbacks. For example, PT may work on ankle flexibility to enable ambulation, while OT might simultaneously modify the patient’s clothing fasteners to allow safe independent dressing.

Effective collaboration rests on clear communication, shared goals, and a common language to describe progress and obstacles. When therapists align around a unified care plan, treatment can be timed so that gains in mobility underpin gains in independence, and improvements in function reinforce motivation to persevere through challenging exercises. In hospital corridors and home visits alike, clinicians rely on concise handoffs, timely updates, and agreed-upon milestones that reflect both movement and ADLs.

Research supports this integrative approach. In home-visit rehabilitation, Asano’s cross-sectional study illuminated how liaison between physiotherapists and occupational therapists enhances the quality and consistency of care delivered in patients’ own environments. The findings point to better continuity of treatment plans and more personalized interventions that account for living space, routines, and family supports. When a PT and OT share observations about a patient’s home layout, the plan can adapt to obstacles such as stairs, uneven surfaces, or limited storage, turning constraints into achievable steps toward independence.

Another compelling line of investigation looks at specialized settings where early collaboration becomes part of routine burn care. Schwartzman’s 2024 work explored embedding both rehabilitation specialists into daily burn care. The result was not simply faster physical healing but a smoother, more confident return to function for patients who must relearn basic tasks amid sensitive wounds and changing energy levels. In both cases, the message is consistent: collaboration reduces fragmentation and speeds the return to meaningful life roles.

To translate these findings into everyday practice, clinicians foreground patient-centered aims and environmental fit. OT assessments focus on ADLs such as dressing, bathing, meal preparation, and safety in the home, while PT assessments emphasize alignment, posture, and movement strategies that support gait, reach, and transfer. Yet the most powerful insights come when these strands are woven together: the therapist who can anticipate how a strength gain will translate into a safer transfer, or how a new kitchen aid will enable cooking without exhausting the patient. The environment becomes another partner in rehabilitation, not merely a backdrop.

Interprofessional collaboration does not erase professional boundaries; it clarifies roles and builds a shared repertoire. When a plan accounts for the patient’s goals, preferences, and living situation, it remains realistic and motivating. Communication tools—structured handoffs, weekly case conferences, and shared documentation—help everyone stay on the same page even as the patient moves from hospital to home or to a long-term care setting. The patient, in turn, experiences a unified message and a consistent strategy rather than a series of disconnected therapies.

An important dimension of integration is adapting environments to support independence. OT expertise in assistive devices, home modifications, and compensatory strategies complements PT’s work on strength and control. The combined expertise is especially visible in communities where home visits are essential, or where patients transition directly from acute care to a home-based rehabilitation program. The ability to plan for the home at the outset means that the patient can practice a new activity in a safe, familiar setting, reinforcing confidence and reducing anxiety about performing tasks outside the clinic.

To illustrate how collaboration translates to patient outcomes, consider a patient recovering from a fall who is now navigating stairs and morning routines. The PT may design a progressive strength and balance program, while the OT helps choose and train the use of adaptive equipment, modifies the bathroom to reduce slips, and reorganizes the kitchen to minimize reach and effort. The two streams converge in a practical script: first, the patient improves in motion; second, the same patient uses that motion to complete dressing, bathing, and meal preparation with greater autonomy. The synergy is palpable when a caregiver notices fewer hesitations, longer endurance, and improved mood as tasks become doable again.

Professional growth within rehabilitation teams also benefits from a culture of continuous learning and shared evidence. Clinicians keep up with research questions about best practices in interprofessional care, seeking out ways to streamline assessment, standardize progress notes, and tailor interventions to the patient’s cognitive, emotional, and social context. The literature, including the studies cited above, provides a roadmap for teams to implement collaborative routines with fidelity: joint rounds, co-treatment sessions, and a commitment to seeing the patient as a whole rather than as a collection of impairments. In this way, PTs and OTs become co-pilots in a patient’s journey toward reengaging with life.

Beyond the hospital and clinic walls, the collaboration extends to families and caregivers who become partners in daily practice. When home environments are taken into account from the outset, caregivers gain clear instructions and practical strategies. They learn safe transfer techniques, adaptive ways to assist with dressing, and tips for preserving energy during routine tasks. This shared responsibility nurtures a sustainable path to independence, one that respects the patient’s pace and the family’s routines. In turn, patients emerge with not only improved scores on functional tests but also renewed confidence in their ability to participate in work, hobbies, and social life.

The trajectory of care is not linear, nor should it be expected to be. Recovery often involves fluctuations in strength, pain, motivation, and environmental demands. A robust PT-OT collaboration provides a flexible framework that can adapt to these ebbs and flows. Regularly revisited goals help the patient understand the next right step, whether that step is advancing a balance exercise, practicing a self-care task, or negotiating a new routine altogether after a setback. The capacity to adapt—and to translate movement improvements into practical competence in ADLs—is what ultimately sustains progress and preserves dignity throughout rehabilitation.

Finally, clinicians recognize that the most effective rehabilitation is not the sum of its parts but a synchronized sequence that honors what the patient values. The joint language of PT and OT—strength, balance, and endurance alongside independence, safety, and meaningful activity—creates a unified narrative of recovery. In this frame, the choice between PT and OT ceases to be a rigid either-or decision and becomes a question of timing, environment, and goals. When movement gains are paired with tasks that restore independence, the patient experiences a holistic return to life—one that is greater than the sum of its parts.

In practice, interprofessional collaboration is facilitated by a culture that normalizes joint problem-solving and shared accountability. For a practical discussion of how OT collaborates with other healthcare professionals How do Occupational Therapists Collaborate with Other Healthcare Professionals, teams can explore templates for communication, shared goal-setting, and coordinated discharge planning. This continuous exchange not only aligns clinical aims but also respects the patient’s home context, literacy level, and cultural preferences as central determinants of success. When families observe a united team that speaks with one voice about progress, encouragement replaces hesitation, and adherence to the rehabilitation plan strengthens.

For a deeper dive into the evidence supporting integrated PT and OT care, consult the broader body of research and reviews that examine how these disciplines complement one another in diverse settings. A foundational study and subsequent literature emphasize that early, ongoing collaboration—embedded in daily routines and reinforced across care transitions—yields more consistent care, fewer gaps, and more rapid attainment of functional independence. You can explore the original report at the following external resource: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6583712/.

Final thoughts

In navigating the complexities of patient care, understanding the distinct yet complementary roles of physical therapy and occupational therapy is crucial for business owners. By acknowledging their differing goals, methods, and patient populations, and by leveraging the advancements in technology along with the power of interdisciplinary collaboration, healthcare providers can enhance the quality of care they offer. Both PT and OT play integral roles in fostering recovery and promoting independence, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for patients. As business owners, investing in knowledge about these two fields can have a profound impact on service delivery and patient satisfaction, paving the way for a more effective healthcare practice.