Occupational therapy equipment is pivotal for enhancing the daily lives of individuals with varying physical, cognitive, and emotional needs. It serves as an essential foundation for rehabilitation and fosters independence in daily activities. As business owners in the healthcare or therapeutic sectors, understanding this equipment—not merely as tools but as instruments of empowerment—is crucial. This article will explore three key areas: a comprehensive overview of occupational therapy equipment, the specific types and their uses, and the vital role these tools play in rehabilitation and daily living. Through this exploration, business owners will gain insights into how they can best serve their clients, promote wellness, and deliver effective solutions.

From Tools to Triumph: A Comprehensive Exploration of Occupational Therapy Equipment

Every day, the most meaningful improvements in a client’s life arise not from a single therapy technique, but from a thoughtfully chosen toolkit that aligns with goals, respects preferences, and sits at the intersection of body, mind, and environment. In occupational therapy (OT), equipment is not a collection of gadgets but a structured language. It communicates intention, supports safe practice, and gradually reveals what a person can achieve when given the right kind of support at the right time. The equipment an occupational therapist selects embodies a deliberate decision to shape activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) into something that feels attainable, engaging, and even enjoyable. This chapter offers a cohesive view of the OT equipment landscape, tracing how different categories of tools work in concert with assessment findings, client goals, and clinical reasoning to foster independence across the lifespan. It is a narrative about how physical design, sensory science, cognitive challenge, and emotional regulation converge in practical, real-world settings, and how therapists translate this convergence into meaningful daily gains for their clients.

At the core of equipment-based OT practice lies a simple truth: independence grows when tasks are tailored to the person, not the other way around. A tool’s value is not measured by complexity or novelty but by how well it supports a specific activity—such as buttoning a shirt, sorting pills, preparing a simple meal, or managing a morning routine. This orientation toward individualized goals anchors the selection of equipment in evidence-based practice and standards, a framework often summarized in professional resources and guidelines. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) guides practitioners to consider factors such as sensory processing, motor control, cognitive demands, and safety when choosing tools, while also recognizing that equipment must be adaptable to changing needs over time. In practice, that means an OT might start with a broad assessment of hand function, grip, and coordination; sensory profile; posture and balance; and the person’s daily environment. The next step is to assemble a compact, purposeful set of tools that support the person’s current tasks and gradually introduce higher demands as competence grows. When a plan is well anchored in client-centered goals and environmental considerations, equipment becomes a bridge between therapy room activities and home and work life.

One prominent category in the OT equipment repertoire is sensory integration tools. Sensory regulation often serves as the gateway to broader engagement in activities. For children with sensory processing differences or autism spectrum disorder, tools such as textured boards, vibration-based toys, and sensory bins offer controlled opportunities to explore tactile input, yet in a way that reduces overwhelm. Textured sensory boards might present a sequence of surfaces with varied textures—rubbery, coarse, smooth, ridged—inviting exploration and gradual desensitization. The clinician observes how the client modulates arousal, how attention shifts with different textures, and how tactile feedback supports or distracts from task engagement. Vibration toys, deployed judiciously, can be calming in some individuals or alerting in others, helping the therapist tailor a sensory input pattern that optimizes focus during activities such as writing, cutting with scissors, or assembling a simple puzzle. Sensory bins—containers filled with rice, beans, or other safe materials—offer a multisensory sandbox where kneading, scooping, pouring, and stabilizing pressure build coordination, motor planning, and bilateral integration. Each tool is chosen not for novelty but for its potential to stabilize sensory input, reduce anxiety, and scaffold functional participation. In many cases, weighted blankets or other deep-pressure strategies are used to provide a predictable, soothing input at night or during lengthy therapeutic tasks. These strategies help regulate alertness and create a platform from which more complex motor and cognitive work can proceed. The merit of such tools lies in their ability to address the person’s sensory rhythm, enabling smoother transitions between activities and reinforcing a sense of security that is essential for learning.

Adjacent to sensory regulation is the domain of fine motor and upper-extremity development tools. The hand is a gateway to independence, and OT equipment in this area aims to rebuild strength, dexterity, and coordination through repetition that is purposeful and engaging. Therapy putty, offered in varying resistance, provides a versatile medium for repetitive hand exercises that blend strength training with tactile feedback and colorful stimulation. The resistance levels can be tuned to the individual’s capacity, gradually increasing as grip improves and fatigue declines. Grip strengtheners, which range from simple spring-loaded devices to more elaborate hand exercisers, serve as transfer tools to everyday tasks: opening a stubborn jar, turning a key, or gripping a utensil with confidence. Pegboards, lacing boards, and finger-precision tools challenge dexterity and bimanual coordination while also offering a tangible sense of progress as the client completes increasingly complex configurations. Adaptive utensils and dressing aids extend the reach of hand skills into daily routines, turning a once-frustrating task into a sequence of manageable steps. The overarching goal is not merely to improve grip or finger strength in isolation but to cultivate the smooth, coordinated movements that make activities such as buttoning a shirt, cutting a sandwich, or manipulating small fasteners feasible and reliable. In this realm, therapists consider hand architecture—forearm and wrist alignment, scarring or stiffness, proprioceptive feedback—and tailor equipment to accommodate the client’s anatomy and preferences. The result is a body of practice in which progress is visually and tangibly evident: a client can tie laces with decreased effort, assemble a simple craft, or perform a handwriting exercise with less fatigue. The continuity between therapy activities and home tasks becomes a source of motivation and a proof of capability.

Functional mobility and postural support equipment form another vital pillar in the OT toolkit. For individuals with spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis, or developmental challenges, equipment that supports posture, balance, and weight-bearing activities opens access to a broader range of experiences and tasks. Standing frames, sit-stand aids, and adaptive seating systems provide the scaffold for safe movement and upright posture, which, in turn, facilitate respiratory function, circulatory health, and core strength. The therapeutic value emerges not only in the mechanical support but also in the repeated activation of muscle groups during functional tasks. A well-fitted chair or stand assist allows a client to engage in activities such as meal preparation, work simulations, or social participation at the table without compromising alignment or comfort. The integration of mobility aids with sensory and fine motor tools creates a holistic approach; for example, a client might stand with postural support while manipulating therapy putty or completing a sequence on a pegboard, reinforcing the synergy between gross motor control, fine motor precision, and spatial awareness. In practice, this integration is achieved through careful assessment of postural tone, symmetry, weight distribution, and endurance, followed by an equipment plan that supports gradual loading, safe movement, and meaningful participation in activities that matter to the client.

Electrotherapy and neuromuscular reeducation devices also feature prominently in rehabilitation curricula and clinical practice. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and other electrical stimulation modalities can help manage pain, reduce muscle atrophy, and promote nerve recovery in certain contexts. These tools are not stand-alone cures but components of a broader, active treatment plan that combines manual therapy, exercise, education, and environmental modification. When used, they are applied with careful safeguarding: appropriate dosing, monitoring for adverse responses, and alignment with exercise strategies that maximize benefits while minimizing risks. The presence of electrotherapy in the OT toolbox underscores how modern rehabilitation blends physical sciences with functional goals. It reinforces the idea that equipment must be integrated into a comprehensive program, rather than treated as a separate, one-off intervention. Practitioners routinely document outcomes, tracking changes in pain, range of motion, muscle activation, and functional performance to determine whether the device should be continued, adjusted, or combined with different approaches.

Alongside these categories, a broad spectrum of everyday assistive devices and adaptive technologies supports independence across home, school, and workplace contexts. Adaptive utensils with built-up handles, dressing aids that simplify fasteners, and keyboard or switch-access software for cognitive and communication tasks extend a person’s capability to participate in meaningful activities. These tools are often less about “replacement” than about enabling the person to perform tasks with less effort, less frustration, and more confidence. The design emphasis is on ergonomics, ease of use, and compatibility with a person’s daily routines. Therapists also consider safety features, adjustable supports, and compatibility with other equipment in the environment. For instance, a kitchen setup might incorporate accessible shelving, non-slip mats, and easy-grip utensils to promote independence in meal preparation. A classroom or office environment might incorporate seating that supports posture and attention, along with cognitive software that challenges memory, attention, and executive function while remaining accessible to the client’s current capabilities. Equipment choices, in this sense, become a translation of therapeutic goals into real-world capability, a step that cements progress from therapeutic sessions into everyday life.

A practical challenge in OT practice is knowing when to introduce or retire a given tool. The decision to add or phase out equipment rests on several intertwined factors: the client’s evolving goals, the success of strategy combinations, safety considerations, and the home or school environment’s conduciveness to practice. Clinicians maintain a dynamic mental model of the client’s functional map, using observations from sessions, feedback from family or caregivers, and standardized assessment data to recalibrate the equipment mix. This adaptive approach ensures that tools remain relevant and motivating, rather than becoming a passive, static inventory. It also supports the emergence of generalizable skills. When a client learns to sequence steps, regulate arousal, and use a sensorimotor strategy in one context, those skills can transfer to others—feeding, dressing, hygiene, or even community participation. In this light, equipment is not merely a collection of devices; it is a system that supports learning, memory, and habit formation across settings.

The field emphasizes reliable sourcing and evidence-informed practice, and practitioners routinely consult authoritative guidance to ensure that equipment choices reflect current knowledge. AOTA resources help clinicians navigate standards, performance benchmarks, and the practical implications of equipment use, guiding decision-making about what to purchase, how to introduce a tool, and how to measure outcomes. This emphasis on evidence and standards is complemented by a client-centered orientation that places preferences, sensory responses, and daily life contexts at the center of planning. The result is a therapy that respects the person’s autonomy and dignity while providing a scaffold that makes possibility feel tangible. If a reader wishes to explore a curated overview of equipment standards, performance, and practical applications beyond individual practice, a comprehensive external resource offers a detailed synthesis of these principles and case studies to illustrate how theory translates into everyday impact. For practitioners and educators seeking a reliable point of reference, this resource provides standards, performance benchmarks, and practical guidance for selecting, using, and evaluating equipment. (External resource: https://www.therapysource.com/occupational-therapy-equipment-guide)

In terms of professional development and knowledge sharing, there is also value in accessible, evidence-based online resources that collate standards, research findings, and clinical tips. One practical way practitioners stay current is by consulting guides that merge clinical insight with real-world case studies. For those who want a concise entry point to the topic, a resource focused on the practical applications of equipment can illuminate how a given tool is used across contexts—from pediatric clinics to adult rehabilitation settings. The emphasis remains the same: equipment should be chosen and used in a way that strengthens functional independence, respects the client’s values, and fits within the realities of daily life. To support ongoing learning, therapists may also refer to internal or external materials that summarize best practices, integration with environmental modifications, and strategies for engaging clients whose needs vary with time and circumstance. In practice, this translates into a holistic, flexible approach where the equipment is tuned to outcomes, not the other way around.

For professionals and students seeking a succinct path through the complexity of equipment choices, it is helpful to consult a targeted, integrative resource that situates tools within standards and clinical reasoning. A compact, evidence-informed guide can connect the dots between a client’s sensory profile, motor capabilities, cognitive load, and the environmental constraints in which daily tasks unfold. It can also illustrate how a sequence of interventions—starting with gentle sensory regulation and moving toward purposeful manipulation and problem-solving—builds a transferable skill set. The guiding principle remains consistent: equipment is most valuable when it enables authentic participation. When a client can prepare a simple snack, dress for the day, or complete a self-care routine with diminished effort and greater confidence, the therapy has achieved its aim. The practical dynamics of using OT equipment—how to select, adapt, and evaluate tools in response to a client’s progress—continue to evolve as research clarifies how sensory input, motor practice, and cognitive strategies interact within real-life tasks. In every case, the therapist’s judgment and the client’s lived experience co-create the path from intervention to independence.

In closing this overview, the chapter ties back to the central idea that occupational therapy equipment functions as an enabling environment rather than a standalone intervention. The tools are the means by which therapists translate goals into actionable steps, and by which clients reclaim a sense of competence in daily life. This perspective reframes equipment from a passive assortment into a dynamic, responsive system that evolves with the person. It also invites ongoing collaboration with caregivers, educators, and other health professionals to ensure that environments—home, school, and work—are aligned with therapeutic objectives. For readers who wish to explore further how specific tools are integrated into daily routines and how environments can be optimized to support ongoing independence, a related resource offers deeper guidance on the intersection of equipment, practice settings, and evidence-based outcomes. See the internal link for practical considerations about selecting and using equipment in clinical settings: Tools and Equipment for Occupational Therapists. (Internal link) If you are seeking a broader, externally validated synthesis of equipment standards and practical applications, the external resource cited above provides a detailed guide that complements clinical coursework and practice.

Tools for Daily Triumph: How Occupational Therapy Equipment Shapes Independence

When a person faces the daily task of dressing, feeding, or navigating a busy environment, the line between struggle and possibility often rests on the tools within reach. In occupational therapy, equipment is not simply material; it is a carefully chosen partner that translates assessment insights into practiced capability. The tools therapists select sit at the intersection of science and everyday life, acting as intermediaries that help people reframe what they can do, not what they cannot. They are the physical embodiment of goals, turning intention into action and intention into independence. Through this lens, equipment becomes less about novelty and more about predictability, safety, and the confidence that comes with mastering the actions that mark a person’s life each day. A well-chosen set of tools aligns with a person’s strengths, respects their pace, and respects the contours of their environment, creating a bridge from deficit to potential that is as unique as the individual it serves.

The spectrum of occupational therapy equipment is broad and nuanced, reflecting the diverse challenges clients bring to therapy. It is organized not as a catalog of gadgets but as a spectrum of approaches that support physical, cognitive, sensory, and emotional development. At one end lie sensory integration tools—textures, tactile boards, and sensory experiences that help regulate arousal, sharpen focus, and improve motor planning. These tools are especially relevant for individuals with sensory processing differences, including those on the autism spectrum, as well as for people recovering from neurological events where sensory modulation supports safer, more purposeful movement. The aim is not simply to stimulate the senses but to shape the nervous system’s responses so that daily tasks become more stable, more predictable, and less effortful. This is where quality and safety standards converge with therapeutic intent. The literature that guides practice emphasizes the need for evidence-informed choices, ensuring that sensory activities are purposeful and structured to support functional outcomes rather than merely providing novelty or distraction. AOTA’s guidance underlines the role of sensory-based interventions as part of a broader, client-centered plan, with careful attention to individual differences and long-term goals. For practitioners seeking practical guidance on choosing the right tools, see Tools and Equipment for Occupational Therapists.

Meanwhile, fine motor development remains a core area where equipment makes the difference between passive participation and active mastery. Hand function is a gateway to independence, and a range of manipulative materials supports that pathway. Therapists introduce tools that gently challenge grip, finger control, and dexterity through tasks like pinching, releasing, and precise placement. These activities may involve peg-like boards, stringing tasks, and precision tools that encourage eye-hand coordination in a way that mirrors everyday activities—picking up a button, threading a bead, tying a shoelace. The emphasis is on graded difficulty: starting with large, easy-to-manage pieces and progressively moving toward smaller, more intricate tasks as strength and control improve. The aim is not to overwhelm but to cultivate a sense of competence, a feeling that the body can meet the demands of real life with confidence. In this approach, the clinician’s role is to select materials that provide just enough resistance and feedback to promote growth without causing frustration or fatigue. The result is a quiet but powerful sense of progress that can transform a child’s play into purposeful practice, and practice into proficiency.

In parallel with these motor-focused tools, weighted items provide deep pressure input that can calm the autonomic nervous system and improve readiness for learning and task engagement. The preference for deep pressure input is not a cosmetic choice; it is grounded in sensory science that links proprioceptive feedback to regulation and organization of behavior. When a person experiences balanced input, their muscles relax, their breathing steadies, and their attention becomes steadier. This has broad implications: a calmer nervous system supports better attention to a caregiver’s instructions, more deliberate movement, and fewer avoidance responses that often derail participation. The exact configuration of these weighted supports is individualized, balancing the need for comfort, safety, and therapeutic benefit. Clinicians monitor how the person responds across sessions and adjust the weight, distribution, and duration of exposure to keep the experience both effective and tolerable. This is not a one-size-fits-all solution; it is a dynamic component of a larger, person-centered plan that respects autonomy and consent while providing the reassurance that comes from predictability.

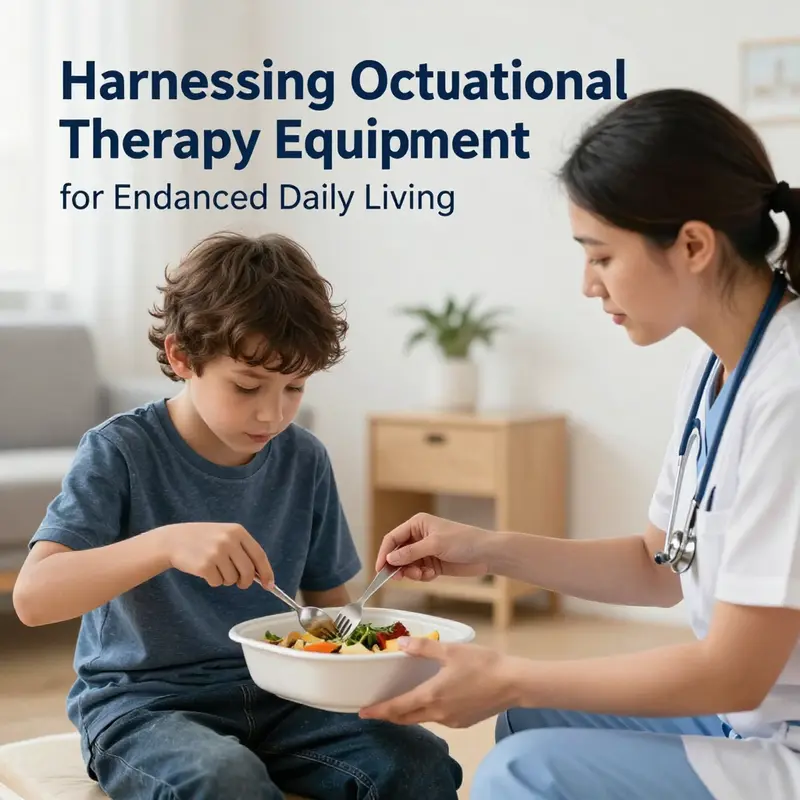

Functional mobility and activities of daily living (ADL) form another central axis around which equipment rotates. Adaptive utensils and dressing aids extend the reach of the person’s capability, enabling tasks that might otherwise require assistance. Reaching tools, zipper pulls, zippers with larger tabs, and button hooks are not merely conveniences; they are lifelines that preserve dignity and independence in self-care. When people can prepare meals, dress themselves, or bathe with minimal help, the sense of agency they retain influences mood, motivation, and their willingness to engage in rehabilitation. In many cases, the choice of these aids is informed by an environment assessment that considers the layout of a home, the rhythm of daily routines, and the presence of family or caregivers who provide support. The goal is to harmonize the individual’s abilities with the world they inhabit, reducing barriers and enabling smoother participation in everyday life.

Therapeutic exercise gear completes the circle by anchoring strength, endurance, balance, and coordination to functional outcomes. Resistance bands and equipment designed to stimulate limb movement play a critical role in post-operative rehabilitation, neurological recovery, or management of chronic conditions that affect mobility. The key here is progression, ensuring that activities remain meaningful and aligned with real-life tasks. A therapist might guide a patient through a sequence that begins with gentle resistance and evolves to more complex, multi-joint movements that mirror daily actions—lifting a grocery bag, reaching overhead to retrieve an item from a shelf, stabilizing the trunk to maintain posture while performing a task. The equipment thus becomes a conduit for improving joint stability and overall functional capacity, reinforcing the person’s ability to participate in routines that matter most to them. Safety features, ergonomic design, and tailor-made progressions are non-negotiable, because rehabilitation is not merely about strength in isolation but about the reliability of movement under realistic conditions.

Cognitive and emotional support tools—often subtle, sometimes digital—complement the physical apparatus by addressing attention, memory, planning, and coping strategies. Cognitive training software, tactile organizers, and structured cueing systems can help individuals manage cognitive load, navigate complex sequences, and maintain motivation over time. The integration of these technologies into therapy plans is deliberate, grounded in an understanding of each client’s cognitive profile and daily demands. The overarching purpose is to create a cohesive day that feels navigable rather than overwhelming. Emotionally, the presence of familiar, controllable tools can reduce anxiety and foster a sense of preparedness. Therapists work with families to embed these supports into home routines, encouraging consistency and reinforcing what is learned during sessions. The effect is a ripple: improved mood, better engagement in tasks, and a greater sense of control when facing new or daunting activities.

All of these equipment choices are anchored in careful assessment and ongoing evaluation. The selection process begins with a thorough examination of the person’s strengths, challenges, goals, and living context. It continues with risk assessment to ensure safety in use and compatibility with other therapies or medical conditions. As practitioners develop a treatment plan, they weave together multiple tools to address the person’s needs across domains. AOTA guidance, research evidence, and clinical experience inform these decisions, but the planning remains deeply personal. The therapist collaborates with clients and families to select, trial, and adapt equipment in ways that honor preferences and values while preserving dignity. The home and school environments are treated as extensions of the therapy room, and the equipment chosen for these settings is chosen with the same rigor, safety, and user-centered focus as devices used in clinical spaces. In this way, the equipment becomes not a gadget chest but a strategic arsenal that supports participation across contexts, from morning routines to community activities and work-related tasks.

The social and environmental dimensions of equipment use deserve careful attention as well. A well-fitted tool is only valuable if it integrates with the person’s routines and environment. Therapists evaluate how devices interact with spatial constraints, lighting, noise levels, and caregiver availability. They consider how families can incorporate tools into everyday life without adding complexity or friction. This is a collaborative process, one that invites feedback, experimentation, and adjustment. It also recognizes that the purpose of equipment is not to replace instruction or practice but to enable meaningful practice. The person who uses the tools is the central authority in their own life; the equipment simply supports and amplifies their agency. When families are engaged, the path from assessment to achievement becomes clearer, and the likelihood of sustained independence increases.

A strong emphasis on standards and best practices anchors these efforts. The field continually studies how tools influence outcomes, seeking methods to optimize effectiveness while safeguarding safety. Therapists stay current with evolving guidelines, ensuring that equipment choices reflect current understanding of sensory processing, motor learning, and cognitive strategy use. The emphasis on evidence-based practice does not constrain creativity; it channels it toward interventions that are accountable, replicable, and adaptable across diverse client populations. In the end, the equipment that travels from clinic to home is part of a broader continuum—assessment informing intervention, practice shaping competence, and independence becoming a lived reality. The power of these tools lies not in their novelty but in their reliability, in the predictable support they offer when a person attempts tasks that may have once felt out of reach.

As the field evolves, so too does the integration of technology and data in equipment-supported therapy. Digital platforms, sensor-based feedback, and adaptive interfaces promise richer, more personalized experiences. Yet the human dimension remains essential: therapists interpret data, calibrate difficulty, and maintain the relational core of rehabilitation—the trust that clients place in their therapists and in themselves. Equipment becomes a shared language, a way for clients to communicate progress, setbacks, and goals without words. It invites collaboration, curiosity, and resilience, guiding learners through incremental challenges toward meaningful participation in daily life. The result is a therapy that respects both the science behind movement and the art of living well. It is a reminder that equipment is not an end in itself but a means to cultivate autonomy, participation, and a sense of belonging in the world.

For educators, clinicians, and families seeking a practical frame, the message is clear: choose tools with intention, align them with real-world tasks, and monitor progress with humility and curiosity. The most effective equipment helps people practice what matters most—self-care, productive work, healthy social participation, and the daily rituals that create a sense of home. It is not the quantity of tools that matters but the harmony of approach, safety, and empathy that accompanies their use. When this harmony exists, equipment ceases to be a backdrop and becomes an active partner in learning, growth, and well-being. The result is more than skill development; it is a transformation of daily life, a series of small, steady steps that lead toward greater independence and improved quality of life. For practitioners and families alike, that is the enduring value of occupational therapy equipment: a thoughtful, steadfast companion on the journey from challenge to capability.

External resource: https://www.therapysupplies.com.au/blog/a-complete-insight-into-occupational-therapy-equipment-standards-performance-and-practical-applications/

Bridging Recovery and Routines: How Occupational Therapy Equipment Shapes Everyday Independence

Across rehabilitation and daily living, equipment used in occupational therapy acts as a carefully tuned bridge that links gains earned in therapy to the rhythm of everyday life. It enables people to reimagine what is possible in routine tasks that define independence. When a clinician introduces a tool, the focus is on function, confidence, and the patterns it enables, not just the device itself. In this sense, equipment becomes part of a conversation between remaining capacities and the deliberate adjustments that reshape activities into meaningful routines. The work of OT equipment is to reframe tasks in ways that align with a person’s environment, values, and pace of recovery, turning therapy sessions into practical practice embedded in daily life.

In rehabilitation settings, adaptive tools are chosen to match specific impairments while considering real-world action. A therapist looks at how a hand, arm, or shoulder contributes to practical tasks, not in isolation but in context. For someone recovering after a neurological event, precision, grip, and coordination take center stage; for someone with chronic pain or arthritis, the emphasis is on reducing strain while preserving function. The aim is an adjustable toolkit that can scale with progress, with a design philosophy that values simplicity, ergonomic form, and intuitive use to lower cognitive load and fatigue while supporting participation.

The home environment is where therapy translates into daily life. Bathing, dressing, meal preparation, and safe mobility become stages for demonstrating growth, sustaining motivation, and fostering independence. Tools with larger handles, dressing aids that reduce dexterity demands, and grip-strengtheners that provide guided resistance allow individuals to practice meaningful tasks with less frustration. The goal is not to rush independence but to match supports to the person’s current abilities and future goals.

Technology and evidence-based practice also shape OT equipment. Devices that provide tactile feedback, adjustable resistance, or safe supports can complement hands-on therapy without supplanting it. Digital tools may structure cognitive tasks and track progress while remaining integrated with real-life activities. The best equipment respects each person’s journey, adjusting to evolving needs and environments so that progress remains measurable and meaningful in daily life.

Ultimately, equipment is a partner in participation. When clinicians, clients, and families collaborate, equipment supports routines that look like natural extensions of daily life: preparing a meal, dressing with autonomy, and moving through the home with confidence. The value lies not in the gadgets themselves but in how well they fit a person’s pace, preferences, and living situation. With thoughtful selection and environmental supports, therapy becomes a sustainable practice of living well within one’s abilities, at home and in community.

Final thoughts

Understanding occupational therapy equipment is imperative for any business concerned with health and wellness. These tools not only aid in physical rehabilitation but also foster emotional well-being and increase independence for individuals facing various challenges. By integrating a diverse range of occupational therapy tools into service offerings, business owners can significantly enhance the quality of care provided to clients, fostering both recovery and improved quality of life. The right equipment helps bridge the gap between therapy and everyday living, making it a vital component of therapeutic practices.