Occupational therapy is not just about improving individual skills; it’s about adapting and enhancing the environment to support meaningful participation in daily activities. Business owners need to understand how the occupational therapy environment encompasses not only the physical spaces but also social, cultural, and institutional contexts. Each of these dimensions plays a significant role in shaping the therapeutic process. In the following chapters, we will explore frameworks and models that define the occupational therapy environment, analyze how built environments directly influence therapy outcomes, and discuss the therapeutic potential of natural settings. Understanding these relationships can empower businesses involved in healthcare to create solutions that enhance occupational therapy practice.

The Environment as a Partner in Participation: MOHO, PEOP, and the Everyday Arena of Occupational Therapy

The environment is not simply a backdrop for therapy; it is a living partner that shapes every moment of activity, from morning routines to complex work demands. In occupational therapy (OT), the environment is recognized as a dynamic constellation of physical spaces, social relationships, cultural meanings, and institutional structures that either enable or constrain participation in meaningful occupations. This perspective aligns with a long tradition in OT that treats participation as the outcome of an ongoing negotiation between a person and the contexts in which they live. The chapter that follows, while rooted in theory, seeks to illuminate how these frameworks translate into practice—how therapists read an apartment’s layout, a classroom’s daily schedule, or a community’s accessibility barriers, and then translate those readings into interventions that restore or expand a person’s sense of agency. The environment, in this view, is not passive; it is an active agent in health, a structuring force that can be redesigned to promote equity and participation for people across the lifespan and in diverse settings.

Central to this understanding are two influential frameworks that OT has used to make sense of person–environment–occupation relationships: the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) and the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model. Both place the environment squarely within the grammar of occupational engagement, yet they do so with distinct emphases that complement one another in clinical work. MOHO begins with the person and treats the environment as one of several core determinants of motivation, performance, and habit. It posits that volition, habituation, and performance capacity organize and are organized by the environment, which can present barriers or offer facilitators. Clinicians employing MOHO assess how a given space supports or disrupts routine behaviors, how available resources shape projects and goals, and how the rhythm of a place can align with or fragment a person’s desired occupations. This approach invites practitioners to ask not only what a person can do, but what the environment makes possible for that person to do consistently and with meaning. When therapists diagram the interaction between a person’s motivations and a space’s features, they can identify practical modifications—adjusted lighting to sustain attention, rearranged furniture to enable safer mobilization, or cues embedded into the environment to support a newly forming routine.

PEOP, by contrast, offers a broader, transactive lens that foregrounds the reciprocal exchange among person, environment, occupation, and performance. It directs clinicians to map how environmental factors—physical layout, social supports, cultural expectations, policy barriers, and economic constraints—interact with an individual’s abilities, preferences, and goals to shape participation outcomes. The PEOP model supports a holistic planning process: it orients teams to gather person-centered data about skills and desires while simultaneously auditing environmental affordances and limitations at multiple levels, from the home to the workplace to the community. This framing is especially valuable in complex cases where change must occur across systems—when a client seeks to return to work after illness, or when a family navigates housing constraints that impede safe self-care. What makes PEOP particularly practical in today’s health landscape is its explicit adaptability to diverse populations and settings. It speaks a language that can be shared with family members, school personnel, employers, and community planners, thereby stitching together micro-level interventions with macro-level reforms.

Together, MOHO and PEOP provide a coherent map for occupational therapists who aim to translate theory into meaningful, measurable change. They encourage clinicians to view the environment as a continuous field of influence rather than a fixed stage. In practice, this means clinicians routinely move between assessing a person’s internal drivers and scrutinizing a place’s external design, social networks, and policy environment. The assessment becomes a conversation among possibilities: what aspects of a space can be redesigned, what supports can be mobilized, and what new tools or routines must be learned. The goal is not merely to adapt the person to the environment, though that is often necessary; it is to co-create an environment that supports the person’s participation in occupations that matter most to them. In rehabilitation settings, for example, therapists may team with rehabilitation engineers to integrate assistive technologies into a living space, thus enabling greater independence. A case study reported in recent OT literature highlights how microelectronic assistive devices, tailored to a teenager with rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism, significantly improved occupational performance by aligning environmental supports with her unique neuro-muscular profile. The case underscores a broader principle: a well-matched environment can compensate for limits and amplify existing strengths, thereby expanding the range of meaningful activities that a person can undertake daily.

Beyond the clinical room, the environment’s role extends into mental health and well-being, where natural spaces and outdoor settings are increasingly seen as therapeutic arenas in themselves. Occupational therapists have explored how exposure to nature and participation in purposeful outdoor activities contribute to mood regulation, stress reduction, and the rebuilding of daily structure after periods of instability. This aligns with a growing body of work that treats outdoor and natural environments as legitimate therapeutic contexts—areas where clients can practice decision-making, social interaction, and task sequencing in real-world, motivating ways. The therapeutic value of nature appears not only in direct activity but also in the symbolic meanings embedded in outdoor spaces—the sense of renewal that comes from sunlight, fresh air, and encounters with the living world. When therapists incorporate the outdoors into treatment plans, they simultaneously address physical health goals and psychological resilience. Such practice speaks to a holistic, client-centered model of care that respects both the built world and the natural world as essential elements of health and participation.

To translate these ideas into everyday practice requires structural know-how and interdisciplinary teamwork. The environment’s evaluative work is often collaborative, involving discussions with building professionals, urban planners, policymakers, caregivers, and clients themselves. In addition to direct intervention, therapists increasingly engage in advocacy and education aimed at improving environmental accessibility and equity. The phrase “changing disabling environments to achieve equity through critique and change,” attributed to Law in 1991, remains a foundational reminder that therapy is not only about individuals learning new skills but also about transforming contexts that limit their participation. This perspective elevates environmental modification from a series of isolated tweaks to a public health enterprise that asks what supports, resources, and policies are needed to ensure that every person can participate in meaningful occupation, regardless of their circumstance.

The practical implications of aligning MOHO and PEOP with environmental modification are far-reaching. In homes and apartments, therapists might conduct not only a functional assessment but also a spatial analysis, looking for barriers to safe transfers, kitchen accessibility, or medication management. The aim is to design small, sustainable changes that can be maintained by families. In workplaces, OT practitioners can guide ergonomic arrangements, task simplification, or schedule adaptations that permit sustained performance without compromising safety or social inclusion. Communities are also fertile ground for intervention: improving crosswalks, transit access, or public spaces can extend the range of occupations that clients can pursue, from shopping and socializing to volunteering and creative pursuits. Across all settings, the environment emerges as a lever for change that can be leveraged to support participation across the life course.

To illustrate how this works in a real-world scenario, consider the case of a teenager facing a complex movement disorder that disrupts his ability to interact with daily routines at home and in school. By applying MOHO, the therapist identifies the factors that fuel his motivation to engage in his chosen activities, the habitual patterns that either support or derail his day, and the performance skills that are most in need of refinement or compensation. The PEOP lens broadens the assessment to include family routines, classroom expectations, and the neighborhood’s accessibility. The intervention then blends targeted skill-building with environmental modifications: reorganizing the bedroom for easier transitions, introducing lightweight assistive devices that minimize fatigue, coordinating with school staff to schedule frequent rest periods, and ensuring that his route between classrooms minimizes exposure to crowded stairwells. The result is not a single tool but a re-engineered environment that honors his preferences while reducing friction across settings. The success of such an approach depends as much on the process—listening to the client, mapping environmental barriers, and co-creating solutions—as on the actual changes made in space or routine.

The integration of environment, occupation, and performance becomes even more powerful when we consider the social and cultural dimensions that influence how spaces are used and interpreted. A home that is navigable in one family’s terms may be perplexing or inaccessible to another family with different architectural constraints, customs, or daily rhythms. Cultural sensitivity, therefore, is not a peripheral concern but a central practice in OT. Therapists attend to how cultural beliefs shape the meaning of tasks, how family hierarchies affect decision-making, and how community norms influence participation expectations. When therapists work in schools, clinics, or community centers, they hesitate to implement a one-size-fits-all plan. Instead, they co-create with clients and communities, adjusting goals, expectations, and supports to align with local realities while preserving the client’s autonomy and dignity. This approach is not merely about being culturally aware; it is about building environments that reflect diverse ways of living and valuing occupations, thereby expanding not only what people can do but what they believe they can aspire to do.

Technology also plays a pivotal role in shaping the environmental landscape of OT practice. The collaboration with rehabilitation engineering and the thoughtful integration of assistive devices demonstrate how tools can modify space, expand capabilities, and reduce dependence on others. The narrative is not simply about devices but about the intelligence of their use—how a device is chosen to fit the person’s body, how it integrates with the person’s routines, and how the surrounding environment supports its use across contexts. When a teenager begins to interact with a microelectronic system that responds to his specific tremor patterns, the environment adapts in tandem, allowing him to participate in activities that had become inaccessible. This synergy—between device, space, and person—embodies the OT aspiration: to craft environments that are responsive, adaptive, and humane.

The therapeutic arc described here also highlights the importance of measuring outcomes in a way that respects the environment’s central role. Traditional measures of impairment or speed can miss how a space’s design and social climate alter a person’s sense of competence and motivation. Therefore, therapists often incorporate ecological validity into their evaluations, looking at how well clients can perform tasks in real settings, the durability of environmental changes over time, and the degree to which clients can sustain participation in their preferred occupations. In practice, success is not merely a reduction in symptoms or an increase in task performance; it is a restored sense of agency, a fuller repertoire of meaningful occupations, and a more resilient everyday life in which spaces around us support rather than hinder our participation.

Ultimately, the chapter’s through-line is simple and powerful: the environment is not a neutral stage but a capacious, malleable field that can shape health, inequity, and well-being. MOHO invites us to parse the internal drivers that propel action and the external constraints that shape it, while PEOP pushes us to consider how people, tasks, and contexts co-create outcomes. The environment’s value in OT lies not only in the changes it makes possible but in the ethical stance it embodies—that participation should be accessible, meaningful, and grounded in the lived realities of each person. In a world where daily life is increasingly distributed across multiple settings—home, work, school, community spaces—the ability to read and redesign environments becomes, in effect, an act of advocacy. It is through this lens that therapists seek to align evidence, collaboration, and creativity with a commitment to equity, ensuring that environments become partners in participation rather than barriers to it.

For readers seeking a practical touchstone on how environmental and professional collaboration informs practice, consider the discussion on cross-disciplinary teamwork within OT: How do occupational therapists collaborate with other healthcare professionals?. This link points toward a shared language and approach to sustaining participation across settings, reinforcing the idea that environmental change is most effective when it is anchored in collaboration, research, and client-centered goal setting. The chapter ends with a reminder that environmental work is ongoing, iterative, and deeply implicated in the quest for equity. As spaces evolve, so too do the possibilities for meaningful occupation, and the therapist’s role is to steward that evolution with curiosity, humility, and a steadfast commitment to the person who inhabits each environment.

External reference: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4173625/

Built Environments as Active Partners in Occupational Therapy Outcomes: Designing Spaces for Participation, Safety, and Well-Being

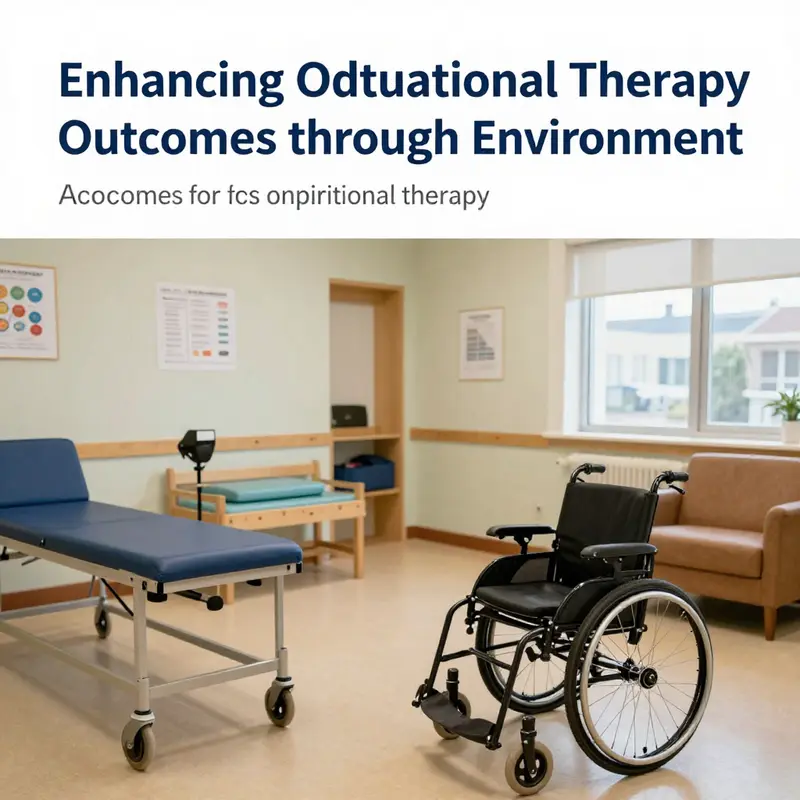

The built environment is rarely a mere backdrop in occupational therapy practice. It is, instead, an active partner that can amplify a person’s capacity to engage in meaningful daily activities or, conversely, erect subtle barriers to participation. In this view, the environment is not simply something to adapt after a diagnosis or a decline; it becomes a dynamic field that therapists assess, negotiate, and reshape in collaboration with clients, families, and interdisciplinary teams. This perspective aligns with foundational ideas in occupational therapy that regard environment as one of the core forces shaping human occupation, alongside motivation, performance skills, and the habitual patterns through which people organize their days. The Model of Human Occupation (MHO) positions the environment as an essential terrain that can either hinder or facilitate participation, and clinicians routinely translate that understanding into concrete actions—modifications, adaptations, and the introduction of assistive technologies that make home, work, and community life more navigable and meaningful. In practical terms, the environment becomes a therapeutic instrument, calibrated to the individual’s needs, preferences, and life context. The overarching aim is not simply to fix deficits but to transform environments in ways that promote equity, autonomy, and dignity by reducing disabling barriers and amplifying enabling supports. This patient-centered stance mirrors the broader ethical commitment to critique and change as pathways to more just systems of care, a principle that has long guided occupational therapy theory and practice.

A central thread in contemporary practice is the recognition that the built environment—comprising architecture, interior design, lighting, acoustics, accessibility features, and the available stimuli within a space—profoundly shapes how clients perform daily occupations. Accessibility is not a binary yes-or-no condition but a spectrum of facilitators and barriers that influence how people feel, think, and act within a given setting. A well-designed space invites independent action while minimizing risk, sustains engagement in purposeful activity, and reduces the cognitive and physical load associated with daily tasks. Lighting, for instance, does more than illuminate; it cues routines, stabilizes mood, and supports visual processing. Noise levels can either soothe or irritate, influencing concentration, communication, and social interaction. Spatial layout matters as well: clear sightlines, logical circulation paths, and sufficiently wide corridors can prevent confusion and accidents, particularly for people with mobility impairments, cognitive changes, or sensory processing differences. The inclusion of nature and natural elements has gained traction as a potent nonpharmacological interventional resource. Exposure to outdoor spaces or indoor biophilic features can elevate mood, lower stress, and foster engagement in activities that feel meaningful and restorative. This shift toward leveraging both built and natural environments reflects a holistic, client-centered philosophy that values context as a therapeutic ally rather than a passive stage for intervention.

The relevance of the built environment to therapy has been reinforced by contemporary research highlighting its broad impact on well-being and therapeutic outcomes. A 2024 study by A. Gawlak underscores the enormous influence that architectural and environmental design can exert on a person’s sense of well-being and the effectiveness of therapeutic processes. In practice, this translates into design choices that reduce physical and cognitive strain, streamline routines, and cultivate a sense of control and autonomy. When a space communicates safety and independence—through features like level thresholds, grab bars integrated into aesthetic design, intuitive wayfinding, and flexible furniture arrangements—clients often display increased motivation to initiate and sustain meaningful activities. In contrast, environments that feel cluttered, confusing, or unsafe can trigger avoidance, vigilance, and fatigue, undermining progress and eroding confidence. The relationship between environment and outcomes, therefore, is not incidental but fundamental to the trajectory of rehabilitation and recovery.

The implications of these insights extend across the spectrum of health conditions and life stages. For people recovering from stroke, the design of the home and community spaces can be a decisive factor in the pace and scope of recovery. Thoughtful modifications—such as arranging frequently used items at reachable heights, ensuring unobstructed pathways for mobility devices, and reducing auditory distractions in learning and therapy zones—can enrich functional independence and participation in restorative activities. For individuals living with dementia, environmental design that minimizes confusion while maximizing orientation can reduce agitation and promote engagement with familiar routines and meaningful tasks. In chronic illness management, spaces that accommodate adaptive equipment, energy conservation strategies, and flexible activity scheduling can support sustained participation in daily life and prevent relapse into inactivity. The common thread across these examples is that the environment, when designed and modified with intention, can lower barriers to participation and elevate the quality of life.

Clinical practice is increasingly collaborative, integrating expertise from rehabilitation engineering, architecture, and environmental design to align physical spaces with therapeutic goals. A case study highlighted in occupational therapy literature illustrates how microelectronic assistive devices—custom-tailored to a teenager with rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism—were embedded within her living environment to reclaim control over adaptive tasks. This example demonstrates a powerful principle: technology is not a standalone remedy but a component of a broader environmental strategy that reframes the person’s possibilities within their everyday setting. The adaptive environment responds to the unique motor, sensory, and cognitive profiles of clients, extending their agency at home, school, and in the community. In rehabilitation settings, therapists frequently collaborate with rehabilitation engineering departments to implement devices and environmental supports that reduce effort, increase safety, and widen participation in preferred occupations. The resulting improvements in occupational performance are not confined to a clinical score; they translate into more consistent engagement in meaningful activities, greater autonomy, and a reimagined sense of self-efficacy.

Beyond the physical structure of spaces, there is growing appreciation for how environmental design mediates social and cultural experiences. The built environment intersects with social supports, cultural norms, and institutional policies that shape participation. A supportive environment must acknowledge diverse bodies, abilities, and ways of living. It should foster inclusive routines that allow people to participate in work, education, leisure, and community life without unnecessary adaptation or supervision. In mental health contexts, therapists have begun to explore the therapeutic value of outdoor and natural environments more deliberately. The natural world can supply sensory richness, predictable patterns, and restorative experiences that complement more traditional clinical modalities. Occupational therapists use these settings to facilitate purposeful activity, whether through gardening, nature-based recreation, or simply time spent in restorative outdoor spaces. The evidence base, including insights from Bishop’s work on natural environments, supports the therapeutic potential of these spaces as part of a comprehensive, holistic approach to care.

To conceptualize the practical implications of these findings, consider a typical home modification or environmental redesign task. The process begins with a thorough assessment of the person’s daily routines, goals, and environmental demands. The OT maps out the person’s habitual pathways, identifies bottlenecks, and recognizes cues in the environment that might trigger unsafe or non-productive patterns. The design response is patient-centered and iterative: it may involve adjusting the layout of furniture, selecting equipment with optimal reach and stability, improving lighting and acoustics, and integrating nature-based elements to support mood and motivation. Importantly, these changes are not merely about safety or compliance; they are about empowering the person to participate in occupations that matter to them—whether cooking, managing finances, dressing, commuting, or socializing. The environment becomes a collaborator in the therapy plan, offering scaffolds that support learning, adaptation, and growth while preserving the person’s dignity and preferences.

In practice, the synergy between environment and therapy extends into schools, workplaces, and communities. In educational settings, for example, classroom layouts that promote visibility, reduce fatigue, and support executive function can enhance students’ engagement with learning activities and social participation. In workplaces, ergonomic redesigns, space planning, and flexible work arrangements can accommodate evolving capacities and support vocational rehabilitation efforts. In community settings, accessible parks, pedestrian networks, and welcoming public spaces enable participation beyond the walls of the clinic, reinforcing the idea that therapy is not confined to sessions but is woven into daily life. Importantly, these contextual adaptations should be pursued in partnership with clients and their families, ensuring that changes reflect the individuals’ goals, preferences, and cultural backgrounds. The process also requires clinicians to advocate for policies and practices that promote equitable access to well-designed environments, recognizing that environmental improvements can yield broad social benefits and reduce disparities in participation.

From a measurement perspective, the impact of built environments on outcomes is best understood through a composite view that considers functional performance, participation, and subjective well-being. Therapists monitor changes in task independence, efficiency, safety, and ability to sustain engagement in meaningful occupations. They also track mood, perceived control, and autonomy, since these factors often mediate the relationship between environmental changes and functional gains. In this sense, the environment plays a dual role: it shapes what clients can do, and it influences how they feel about their capacity to do it. When the physical setting communicates support and possibility, it enhances motivation and reduces the cognitive burden of therapy, allowing clients to devote more attention to the specific skills they are practicing and to the strategies they are learning. The result is a more integrated rehabilitation experience in which environmental design, assistive technology, therapeutic activity, and patient-centered goals converge to produce durable gains in everyday life.

This integrated approach challenges clinicians to adopt a flexible mindset about what constitutes “therapy.” The environment becomes a co-therapist, capable of facilitating repeated practice, reinforcing adaptive strategies, and enabling clients to rehearse real-world tasks in settings that resemble their daily environments. It also calls for interdisciplinary collaboration that crosses traditional boundaries. Architects, designers, and engineers bring expertise about materials, fixtures, and systems that support safety and independence. Clinicians translate that knowledge into practical, person-centered plans and advocate for design decisions that reflect evidence about what works for different populations. When these disciplines align, the resulting environments support sustained participation, reduce dependence on direct supervision, and promote a sense of mastery that often outlives the clinical episode. In this way, the design of spaces—whether at home, in clinics, or in community venues—becomes part of a larger ethical and professional commitment to equitable, client-centered care.

The value of environmental design is not limited to special populations or severe impairments. Even in the general population, thoughtfully designed spaces can support aging in place, prevent functional decline, and promote ongoing engagement in valued roles. For people managing chronic conditions or fluctuating energy levels, environments that accommodate variability—through adjustable lighting, adaptable furniture, and flexible task organization—offer a form of resilience. In this sense, the built environment becomes a strategic asset in public health and rehabilitation, one that aligns with prevention as well as treatment. It invites therapists to extend their reach beyond the clinic walls and to influence the design of homes, workplaces, and public spaces so that participation remains possible across the lifespan and across changing circumstances. The practical implication is clear: environmental design is not a peripheral concern; it is central to achieving meaningful, durable outcomes in occupational therapy.

To illustrate how these ideas translate into everyday practice, consider the following pragmatic synthesis. Clinicians begin with a person-centered assessment that identifies the tasks most meaningful to the client and the barriers currently encountered in daily life. They then propose a design sequence that prioritizes interventions with the greatest potential to restore participation and independence. Simple modifications—such as rearranging a kitchen layout to align with habitual cooking sequences, installing tactile cues along a staircase, or creating a small, organized work area that minimizes clutter—can have outsized effects on confidence and efficiency. More complex strategies might involve collaborating with a rehabilitation engineer to introduce assistive devices that are both technically appropriate and aesthetically compatible with the client’s living environment. The goal is an environment that feels coherent and controllable, where the client can rehearse and refine occupational routines with ease and pleasure. In mental health contexts, access to calming outdoor spaces, predictable routines within a familiar layout, and opportunities for choice within sensory-friendly environments can support engagement in meaningful activities and strengthen therapeutic rapport.

The evidence base for these claims continues to grow, underscoring the importance of intentional environmental design as a component of successful therapy. Environments tailored to individual needs—whether for stroke recovery, dementia care, or chronic disease management—have the potential to substantially improve functional outcomes and quality of life. The practical takeaway for practitioners is straightforward: when therapy planning includes deliberate environmental considerations, the likelihood of durable gains rises. This requires not only clinical skill but also a readiness to engage in multidisciplinary collaboration, to advocate for space design that prioritizes accessibility and autonomy, and to remain attentive to the nuanced ways in which different people experience space and time in their daily lives.

For readers seeking additional perspectives on how the built environment intersects with well-being and therapeutic outcomes, consider exploring contemporary reviews and syntheses that pull together diverse strands of evidence. One accessible synthesis highlights how thoughtful environmental design can contribute to well-being and treatment effectiveness across settings, offering practical guidance for practitioners involved in planning, architecture, and rehabilitation. While the specifics of each setting will differ, the underlying principle remains: spaces designed with empathy, equity, and adaptability in mind can meaningfully enhance participation and recovery. As the field evolves, occupational therapists will continue to refine their understanding of how to harness environmental design as a strategic resource for promoting health, independence, and social inclusion.

In sum, the built environment is not simply a stage for occupational therapy; it is an active agent that shapes what is possible. Through careful assessment, interdisciplinary collaboration, and intentional design choices, therapists can transform spaces into allies that support motivation, safety, autonomy, and well-being. This integrated approach—bridging clinical expertise, architectural insight, and person-centered goals—offers a powerful pathway to equity in participation and a more holistic, durable form of recovery. The evidence base supporting this approach continues to grow, inviting ongoing inquiry into how the environments we inhabit daily can be tuned to maximize human occupation and meaning across diverse populations and life circumstances.

External resource for further reading: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/13/5/189. For related discussions on practical strategies OT practitioners use to adapt environments and promote mental health through environment-centered care, you may also find value in exploring practitioner perspectives and case examples across professional literature. Additionally, to connect ideas with applied practices and real-world examples, consider reading about how therapists adapt environments for patient needs in clinical settings. how do occupational therapists assist in adapting environments for patient needs.

Nature as a Therapeutic Partner: Reimagining Occupational Therapy Environments

In the repertoire of occupational therapy, the environment is not a passive backdrop but a dynamic partner that shapes what people can do, want to do, and come to value in daily life. The environment can be altered to enable participation, and this idea sits at the heart of OT theories and practice models. Among these, the environment emerges as an active agent that interacts with a person’s motivation, skills, and routines to facilitate meaningful occupation. Over time, practitioners have increasingly emphasized natural environments and outdoor spaces as powerful contexts for assessment, intervention, and recovery. This shift toward nature-based practice reflects a broader view that healing, learning, and participation arise from the interplay between person and place, an interplay that can be choreographed to support autonomy, dignity, and resilience. In this light, nature is not merely a referent for outdoor activity, but a therapeutic partner capable of recalibrating stress physiology, sharpening attention, and widening the horizon of possible occupations across ages and life circumstances.

To appreciate the role of natural environments in OT, therapists adopt a holistic lens that mirrors models of human occupation. The environment, along with volition, performance skills, and habitual patterns, sits at the center of everyday life engagement. This perspective resonates with the Model of Human Occupation (MHO) and invites clinicians to assess environmental barriers and facilitators that constrain or enable participation. When a client contends with anxiety, fatigue, or physical limitation, the surrounding landscape—its terrain, weather, lighting, noise, and the presence or absence of green space—can tilt the balance toward engagement or withdrawal. Therapists thus cultivate a practice that moves beyond remediation of deficits toward purposeful modification of enablers that sustain meaningful occupation. The goal is not only to heal an individual but to examine and transform environments that shape health inequities, asking how a home, workplace, neighborhood, or community setting can be redesigned to support participation in roles that matter to the person.

A growing body of work in OT highlights the lived value of natural environments as therapeutic spaces. When therapists observe interventions in patients’ natural settings—homes, yards, parks, or community gardens—they can identify environmental barriers with sharper precision. A community-dwelling older adult might struggle with threshold navigation, uneven sidewalks, or poorly lit entryways; a teen might find sensory overload in a crowded indoor facility but experience relief in a quiet outdoor corner that allows focused practice. These observations inform the intervention plan so activities align with real-world contexts, making goals more attainable and more likely to generalize beyond the clinic. In this approach, the environment is a living touchstone that guides decisions about what to adapt, what to introduce, and how to measure progress in occupation-based terms. The natural environment becomes a toolkit for OT—customizable to reflect a person’s values, culture, and daily rhythms.

The therapeutic promise of natural settings extends beyond convenience. A robust body of research shows that exposure to nature yields tangible benefits for mental and physical health. In OT, this translates into reduced stress, improved mood, better attention and memory, and enhanced self-regulation—all of which support participation in meaningful activities. Practices such as forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) illustrate these effects. Trials in natural settings report reductions in psychological stress and physiological markers of stress after mindful immersion in forest environments. A peer‑reviewed synthesis indicates forest-based experiences can reduce cortisol and foster a sense of calm that can persist across daily tasks. The mechanisms are complex but plausibly linked to the synergy of sensory input in natural habitats—the cadence of wind and birdsong, the visual rest from greens, the tactile richness of soil and leaves. In rehabilitation contexts, these restorative properties support sustained engagement in therapeutic activities by dampening hyperarousal, sharpening focus, and enhancing emotional regulation. When OT practitioners integrate nature-based sessions into treatment plans, they lean on a body of evidence that frames nature as a non-pharmacologic ally on the path to independence and well‑being.

The mechanisms through which nature exerts its effects are multifaceted and widely studied. Sensory ecology offers a compelling lens: natural environments tend to present a broad, balanced sensory field with visual complexity, tactile textures, and soundscapes that are restorative. Negative ions, plant VOCs, and the absence of harsh urban noise may promote physiological calm. Calming acoustics—rustling leaves, flowing water, distant birdsong—offer consistent stimuli that support attentional restoration and reduce cognitive load. VOCs released by plants have been proposed to influence immune function and mood, though exact pathways remain under investigation. The net effect is a subtle recalibration of the autonomic nervous system, balancing sympathetic arousal with parasympathetic regulation. This calm can translate into greater endurance, improved planning, and a greater willingness to engage in challenging occupations.

Linking these responses to practice outcomes, therapists describe how nature-based occupations support meaningful engagement. Gardening, hiking, outdoor crafts, and horticultural therapy provide opportunities to build physical strength, coordination, and endurance while fostering personal growth and social connection. Gardening activities can address fine motor control through seedling manipulation, gross motor strength through bed maintenance, and executive functions through planning garden layouts, scheduling irrigation, and problem-solving around pest management. Horticultural therapy blends botanical knowledge with therapeutic aims, guiding clients to cultivate autonomy while nurturing belonging within a community context. Tending living things and participating in seasonal rhythms can reframe rehabilitation from a deficit model to a process of renewal embedded in ongoing cycles of care and stewardship.

Incorporating natural environments into plans also supports person-centered care. Urban life often restricts green space, yet the healing potential of nature requires intentional design and programmatic support within OT. Therapists advocate for inclusive, nature-integrated spaces that accommodate diverse abilities, ages, and cultures. This might involve accessible community gardens, outdoor therapy zones with adjustable seating and shade, or structured nature-based groups that foster social participation. The aim is to extend therapeutic reach beyond clinic walls so clients can apply skills in their everyday environments. By weaving nature into intervention, clinicians acknowledge that meaningful occupation unfolds best when the environment resonates with values and routines, enabling sustained engagement.

The practical implications of natural environments for OT are illuminated by cross-disciplinary collaborations and real-world examples. In rehabilitation settings, therapists often partner with rehabilitation engineering divisions to integrate assistive technologies within home and community environments. This collaboration illustrates how environmental modification and technology can extend independence. The Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy (2026) presents a case study: microelectronic assistive devices tailored to a teenager with rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism significantly improved occupational performance by adapting the living space to the patient’s needs. The case underscores that disability arises through the interaction of person, task, and environment. When technology, design, and nature intersect—such as a garden path with accessible surfaces, outdoor seating, and sensory gardens that accommodate sensory processing differences—the potential for participation expands in ways that feel natural and meaningful. In other words, when therapists design environments that leverage natural elements and adaptive technology, they create fertile ground for adaptive strategies that can be maintained at home and in the community. The result is a habitat that invites exploration, resilience, and ongoing growth.

Mental health contexts offer a compelling argument for prioritizing natural environments in OT practice. Outdoor and nature-based interventions can alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression, reduce rumination, and promote belonging. The therapeutic value of outdoor activity emerges not only from physical exertion but from restorative rest that nature provides. When clients engage in nature-based activities, they often report higher mood, reduced irritability, and clearer purpose. Clinicians describe how nature-related routines—such as nature walks, seasonal garden tasks, or outdoor creative projects—offer predictable, low-stakes opportunities for clients to re-engage with daily occupations. These activities support autonomy and mastery, which are central to intrinsic motivation and sustained participation. The social dimension of outdoor work—shared gardens, nature clubs, volunteer conservation projects—creates a supportive ecosystem that nurtures social participation, a key determinant of mental health and recovery. In this sense, natural environments extend OT’s reach into the social and ecological fabric of clients’ lives, reinforcing health, environment, and community.

To integrate nature more deeply into practice, therapists borrow from related domains in health and design. They may advocate for policy changes that expand green infrastructure in urban neighborhoods or participate in planning processes to ensure housing or workplace developments include accessible outdoor areas and safe routes for mobility. They may also design in-situ activities that align with a client’s values and cultural practices, recognizing that nature is experienced differently across cultures and life stages. The emphasis remains twofold: tailor activities to what is genuinely meaningful for the individual, and structure environments to reduce barriers to participation while preserving the integrity of the natural setting that supports healing. Nature is not an optional add-on but a foundational element of therapeutic strategy—inviting collaboration across disciplines, from clinicians and researchers to urban planners and community organizers.

In practice, a therapist’s assessment may begin with a home visit that spans indoor and outdoor spaces, acknowledging that daily occupations unfold across a continuum of environments. The clinician notes pathways that enable safe navigation, cues that support memory and routine, and opportunities to incorporate nature-based tasks that align with the client’s preferred occupations. This holistic approach helps ensure that interventions translate into real-world gains. When a client practices cooking in an accessible kitchen with a small adjacent herb garden, or when they walk trails to reinforce gait and balance, therapy becomes an integrated experience rather than a series of isolated tasks. The natural world adds sensory richness that enhances engagement and meaning, offering a sense of place that anchors identity and purpose while providing a practical scaffold for skill-building and mood regulation. The synthesis of natural environments with goal-directed activity embodies a unified approach to rehabilitation that respects the person and the world they inhabit.

For readers seeking practical resources, consider how nature-based mental health strategies intersect with broader OT practice. The OT literature and professional blogs explore how mental health supports can be embedded in everyday environments, including the home and community. A useful entry point is the discussion of how OT supports mental health in everyday life, which highlights nature-informed activities, outdoor mindfulness, and community engagement as viable strategies. Engaging with these resources can help practitioners translate nature-as-a-therapeutic-partner into concrete plans that resonate with clients’ lived experiences. A linked resource on mental health and OT provides a complementary lens on how outdoor contexts and nature-based activities can augment traditional clinical approaches. https://coffee-beans.coffee/blog/occupational-therapy-for-mental-health/

External resource for further reading on nature-based restorative effects: Forest Bathing and Its Impact on Stress Reduction, Journal of Environmental Psychology, which reports substantial cortisol reductions after a forest immersion program. See the external link for a detailed account of findings and methodological considerations. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027249442200135X

Final thoughts

The occupational therapy environment serves as a pivotal factor in enhancing the quality of care and health outcomes for clients. By understanding how various contexts, both built and natural, influence occupational engagement, business owners in the healthcare sector can tailor their services and products to better meet the needs of occupational therapy practices. Investing in these environments isn’t just about meeting therapeutic thresholds; it’s about driving innovative solutions that foster client independence and well-being. In doing so, we not only enhance therapy effectiveness but also enrich the lives of those we aim to serve.